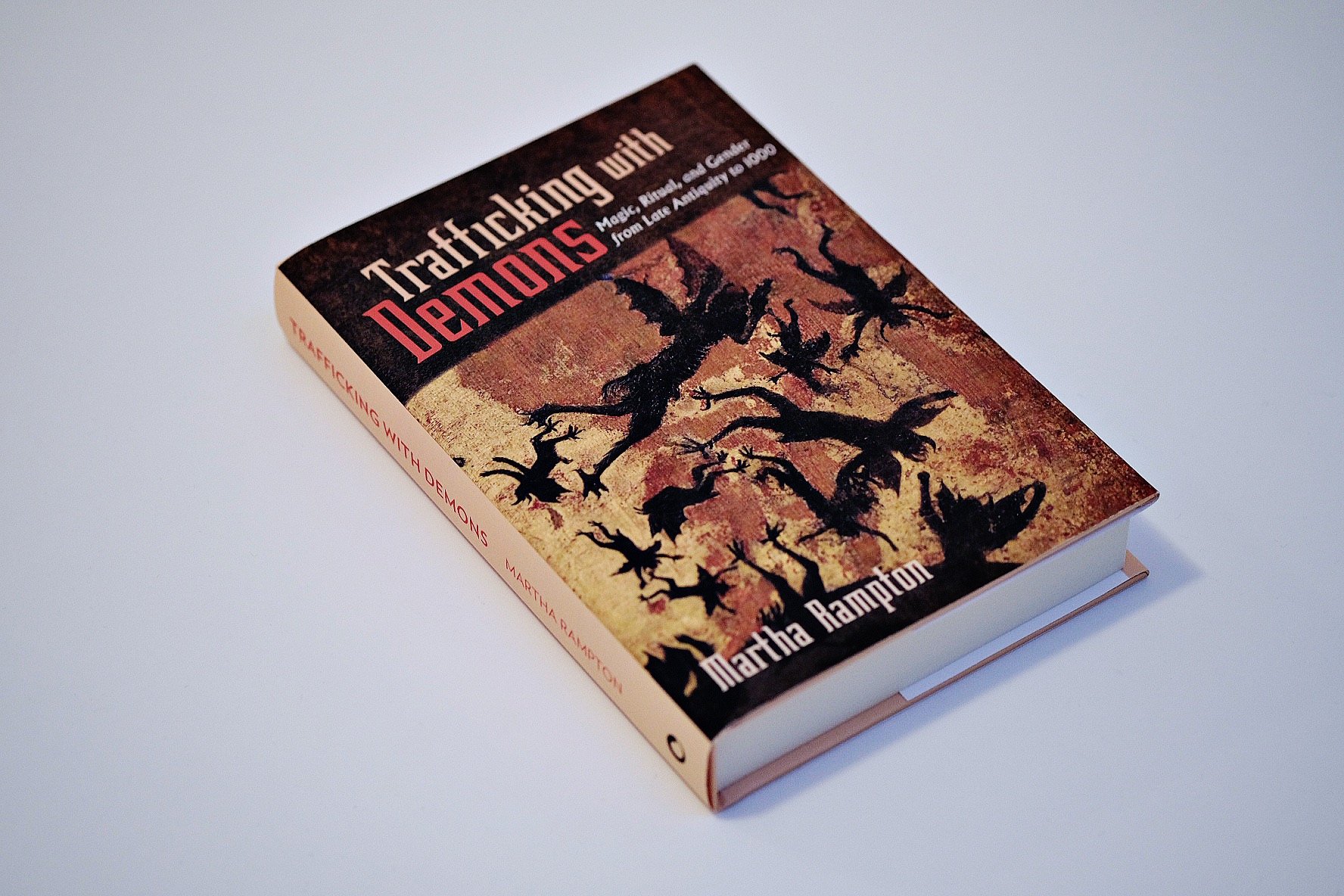

‘Trafficking with Demons’ by Martha Rampton

Review: Martha Rampton, Trafficking with Demons – Magic, Ritual and Gender from Late Antiquity to 1000, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2021, ISBN: 1501702688, 480 pages

This is, obviously, a new historical study, as such at points evidential conclusions arise which contradict or update comparatively recent scholarship. The author, Martha Rampton, is a good example of a post-modern historian, explaining her evidence – documents and events – via the then dominant (and divergent) narratives, upon which she passes no anterior judgement. She is also a very up to date feminist.

Some of the dominant narratives of the period covered in her book will be familiar to many, but others not so much. For example, magic in this period was overwhelmingly defined – by clerical sources and the intelligentsia alike – as involving traffic with demons, whether intentionally or otherwise.

Several features of magic were consistent across the first millennium. For pagans and Christians, demons were natural – not supernatural. These airy creatures of the sublunar region had their place in the great chain of being, below the angels but above humans. By virtue of their incorporeal form, they had powers people lacked, whichallowed them to fly, transmogrify, and permeate material substances. In the pagan worldview, demons could act for good or evil, but by late antiquity they were generally cast as agents of malicious magic.

Christian intellectuals were heir to the view that demons were malevolent, but they introduced a new element to classical demonology by claiming that pagan deities werethemselves demons. They were the fallen angels described in Genesis-cast from heaven with Satan – whose goal was to tempt humans to sin. Traffic with these demons was the very definition of magic, and through this traffic, people were ensnared in a web of wrongdoing. This perspective on demons did not change over the centuries from Christian late antiquity through the early Middle Ages. What did change was the understanding of what precisely constituted traffic with demons. (p. 384)

Such understanding is critical for the Late Antiquity and Post-Roman period. What changes in the Carolingian period is how women are perceived in this equation: the shift our author traces is the reduction in status. Women’s magic in this period becomes a subject of scorn rather than fear.

This has a positive side in that punishments consisted of penances rather than witchhunts but mirrors a corresponding reduction in female status and power in general. During earlier periods power was often based on the home and local influence, and thus women remained powerful or even feared. However, as power shifted to Imperial and religious institutions, this view faded away.

As centralizing governments developed mechanisms for structuring social and domestic life, women's perceived power over occult forces waned concomitantly. The Carolingians eroded the perception of women as effective magical practitioners. Church and secular leaders were determined to nullify myths of female power and to destroy a matrix of symbols that had the potential to mold concepts of reality outside the liminal space in which they were incubated. Female rituals, which made sense of birth, death, and women’s participation in cosmic mysteries, threatened a competing symbolic/ ritual system promoted by an invigorated and increasingly regulated Christianity that understood birth, death, and the role of women in quite a different way. (p. 391)

There are aspects of this book which are of interest beyond the historical context. Of these the subjects of ritual as a maker and definer of narratives and the wielding of symbols that define the culture are foremost.

Controlling the definitions of symbols is highlighted as an aspect of Christianity’s struggle with paganism, magic, and superstition seen as derived from one or both. These latter are considered to be dangerous in that they use symbols, often the same ones, in different ways, subverting the official narrative.

Customs that represent women as powerful for example, are now understood to be dangerous not necessarily because of any inherent, genuine magical power, but because they are misleading and destabilising with regards to the established Christian orthodoxy.

The models of normative female behavior as portrayed in literature do not tell the whole story. It is very likely that in real-life existence, beyond most texts, women’s acumen in magic continued to be respected and feared, and sometimes we get hazy glimpses of this. But what we are able to see clearly is that the elite thought women were ineffectual at working magic with any real consequences because they were generally inept in sacral endeavors, including trafficking with demons. Where concepts of female power and autonomy were kept most alive in symbolic systems and ritual, the Christianassault on rites that bolstered that power was thoroughgoing. (p. 394)

Another example, obvious once demonstrated, is the opposition of nature and the outdoors with the spiritual safety of a Church. Thus, outdoor rituals and customs also represent demonic influence, and even though the power of demons in this period is equally diminished to mere deception, the customs remain problematic as leading people away from God’s intentions and threatening the stability of the state.

Martha Rampton’s book is both definitive and interesting. My only minor grumble is with the quality of the editing and proofreading; on occasion one has to reconstruct a sentence from mangled components. This is no reflection on the quality and rigour of the author or her thesis, which are both first class.