‘The Three Headed Deity’ by Willibald Kirfel

Review: Willibald Kirfel, The Three Headed Deity: Archaeological-ethnological Incursion Through the Iconography of Religions, Bonn: Ferdinand Dümmlers Verlag, 1948.

Original title: Willibald Kirfel, Die dreiköpfige Gottheit: Archäologisch-ethnologischer Streifzug durch die Ikonographie der Religionen, Bonn: Ferdinand Dümmlers Verlag, 1948.

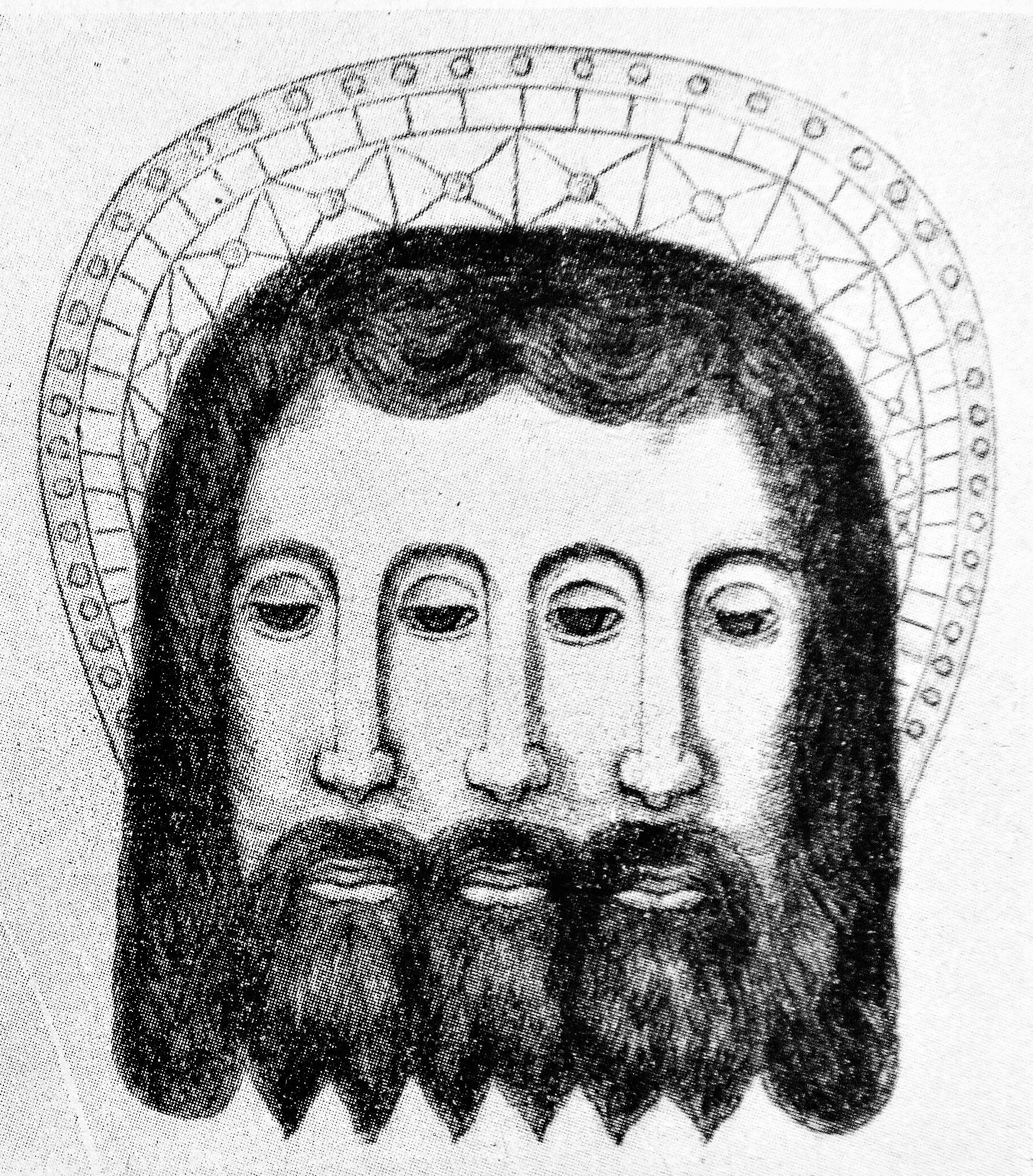

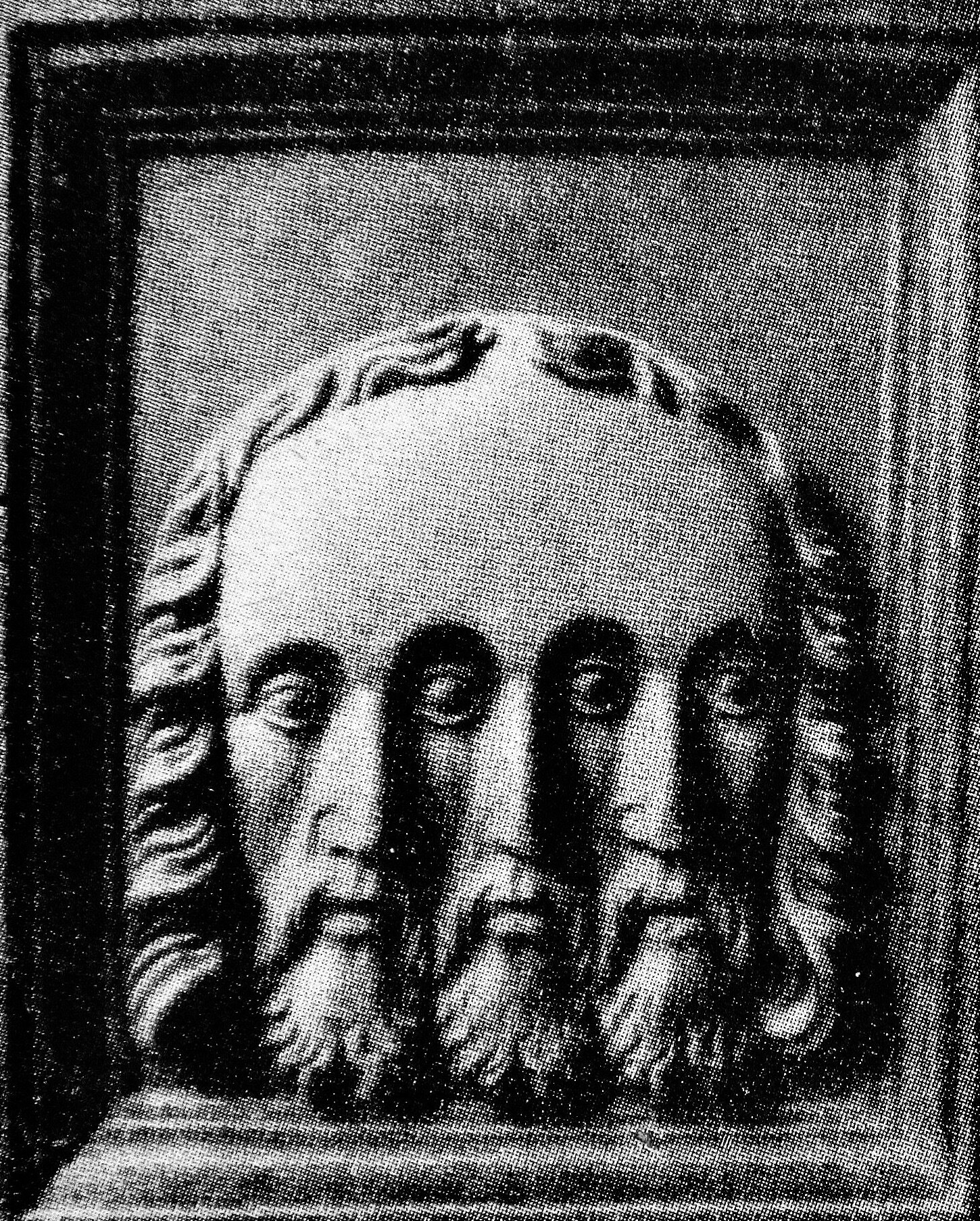

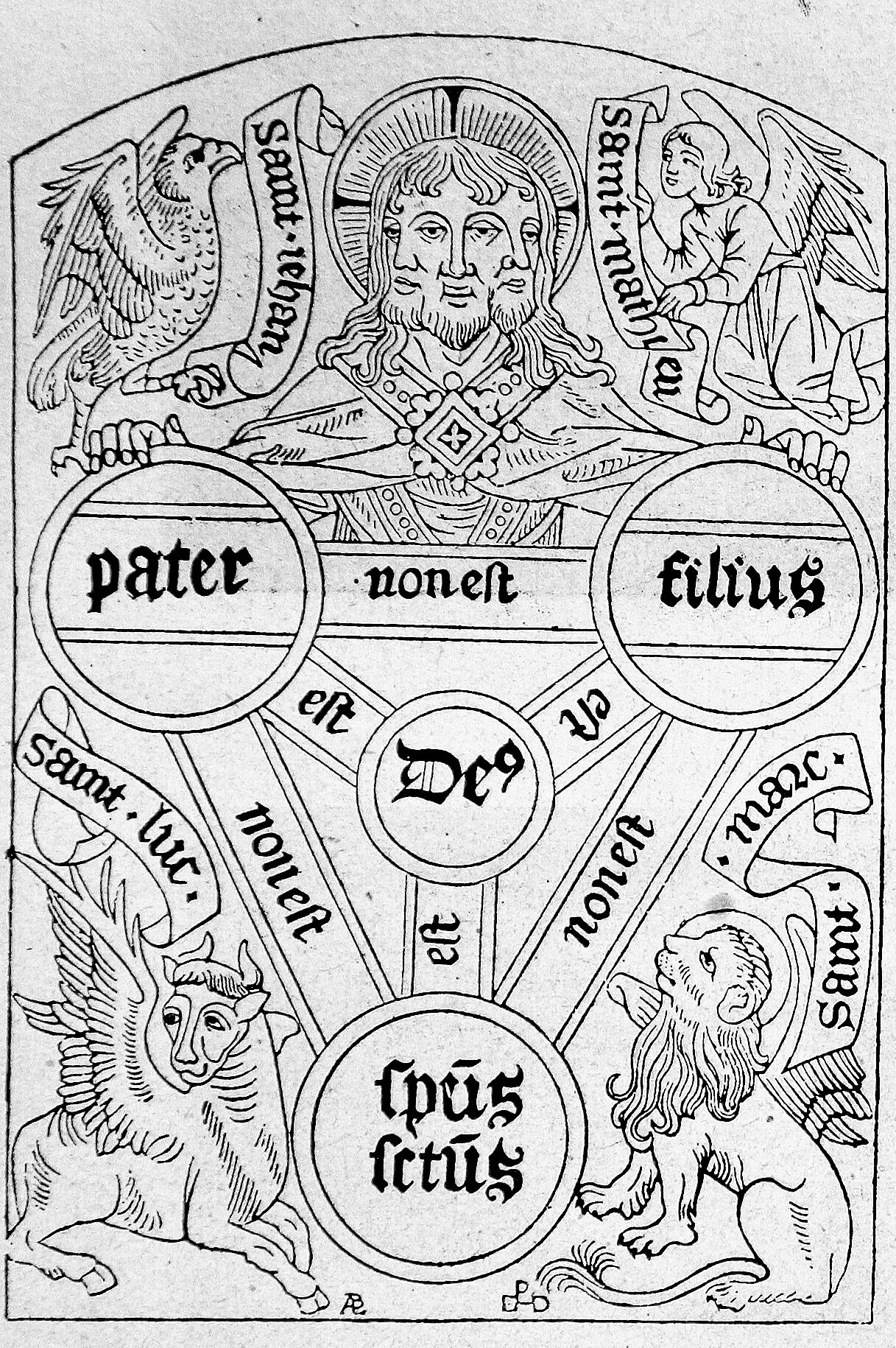

So far, I have not been able to find any proper review of this book. I saw it mentioned in a bibliography, but never quoted or mentioned directly in a text. When I opened my own copy of it, I discovered that it contains several wonderful exemplars of the three headed trinity which, as far as I can see, have never made their way to the internet yet.

I can only guess it is not widely known because it is only available in German and in what seemed to be a humble and small edition. And so, my purpose here is to give an outline of its contents as well as reproducing some of the wonderful pictures from its catalogue.

On a personal note, I also have to add that I purchased this book when I was finishing my MA in the history of art about the three headed and three faced representations of the Christian Trinity in the Andes. Parallel to this, I had the pleasure of studying Sanskrit with Dr. José León Herrera, and so, personally, this book stood at the crossroad of all my interests: Indology, comparative religions and iconography, as well as being a little piece of history by itself.

On the Author and the Historical Circumstances

Willibald Kirfel (1885–1964) was an Indologist from the University of Bonn, who studied and worked there as a librarian and later as a full-time professor. His works are highly specialized, focusing on the cosmography and symbolism of Indian religions (Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism) as well as translations from Sanskrit texts. His main study was of the Puranas, a vast corpus of mythological texts from late antiquity that still influence the current practice of Hinduism.

The current book, as far as I know, is his only work that attempts a comparison between iconographies of both east and west.

It is relevant to mention that Indology played a defining role in the development of Nazi ideology and esotericism or, better put, a particular line of interpretation of it that linked the traditional Indian caste system with the concept of race, mostly based on abusive readings of the Laws of Manu. These ideas shared their roots with 19th century Theosophy and still constitute a genuine rabbit hole within the occult, into which some might easily fall. For a well-informed perspective on the history and problematics of Indology, I highly recommend the book by Willhelm Halbfass, India and Europe: An Essay in Understanding, Albany, NY: SUNY, 1988.

From the few accessible sources it seems impossible to determine in how far Kirfel might have been involved in such exploitative reading of Indology. Yet, in publishing this book only three years after the end of WWII, we certainly witness a scholar trying to survive and to save his field of study from general disaster. In the introduction, he laments how in 1944 his university’s library burned down (p. 3) and asks forgiveness for lacking proper types for printing Sanskrit terms, since they were lost during the bombing raids (p. 6). The book, according to his narrative, was written and finally published during great hardship and against all odds.

It seems that Kirfel came across the three headed depictions of the Christian Trinity in Didron’s Iconographie Chrétienne (1843), as he was interested in the visual similarities between the Buddhist wheel of time, the topos of reincarnation and certain Christian iconographies. He also reproduces several of Didron’s plates in this book. Another source from which he derives many of his hypotheses are the Elements of Hindu Iconography (1914) by the Indian archaeologist T.A. Gopinatha Rao (1872-1919).

A Transcultural Three Headed Deity?

Kirfel’s route through religious iconographies covers an unparalleled wide range of topics, and spans from East to West, taking India, his specialty, as the starting point. We will focus our review on this aspect. Here is a summarized version of the index in its respective order:

The three headed deities of Hinduism

The three headed images in Buddhism (centred in Mahayana)

The three headed deities of Jainism

Traces of the worship of an ancient three headed cult object in Iran

Slavic three headed deities

The three headed Thracian Rider

Three headed deities in the Mediterranean (Hekate, Geryon, Typhon, Hermes)

Three headed and three faced images in Gallo-Celtic areas

Three headed and three faced images in the Christian Middle ages

Three headed deities in Africa

As one could suspect, the range of topics is so broad that several chapters of the book are mostly a beautiful catalogue raisonné. Obviously, we are not going to cover all topics in the current review, and plenty of them have been developed further by researchers since this little book came out in 1948.

What the title and the overview seem to imply, is the existence of a three headed deity that spans across several cultures and eras. And the author discusses the notion that this was a topos, that is a cultural pattern shared by Indo-European cultures spanning from India throughout pagan antiquity. More specifically, he tries to refute the thesis by a certain gentleman named Walther Wüst (1901–1993), who proposed that the three-headed solar symbol was an element belonging to a certain “Aryan heritage” (“arische Erbverwandtschaft”). Kirfel dismisses this by stating how such an “ariophilia” could lead a researcher to losing all objectivity (p. 10).

At this point, what was mentioned above is relevant, since Wüst was not only an Indologist, but a committed member and ideologue of the Nazi party whose research was explicitly aimed at developing concepts of “Aryan culture and language” which were at the core of their ideology.

Yet the figure that is most commonly depicted with three faces in Indian art is the god Shiva, whom Kirfel describes as bearing influences and symbols from diverse ethnicities and as being the “greatest god-concept in Hinduism as well as its most interesting one” (Kirfel, p. 13). The three-headed Shiva is thus identified with Aghora, his most terrible aspect, as depicted in the Elephanta caves or a piece in the Peshawar museum.

The three heads also function as a way of stating the pre-eminence of this god over the other two aspects of the Trimurti (Brahma and Vishnu); thus glorifying him as the greatest deity of all (Mahadeva). Shiva and his son Kartikeya are also depicted with five heads. Shiva’s skull necklace would be a reminiscence of head-hunting and human sacrifice cults, which Kirfel identifies as “non-Aryan” (p. 15) – a clue indicating that despite his critical eye, he also kept using this term as a serious category.

Uneven numbers are considered auspicious for the gods and constitute a ritual pattern in which offerings are made in the Puja (offerings to the gods). In roman late antiquity, Apuleius considered that seven was the best number for conducting ablutions and attributed this custom to Pythagoras (Metamorphosis, XI:1). The god Brahma is commonly depicted as four-headed and is thus inauspicious and not worthy of veneration. He should not be confused with the previous examples, although sometimes in sculpture his fourth head is not visible, as it is carved on the back. Although later mythology relegated Brahma to the role of a Demiurge, it is considered that he might have belonged to a forgotten layer of culture (p. 12).

Other depictions of a three headed Indian deity include Vishnu with strong solar attributes or bearing animal heads belonging to his avatars (Varaha and Narasimha). The hermaphrodite Shiva (Ardhanarishvara) as well as the greater Goddess (Shakti) would also be depicted as three headed, always implying the supremacy of the depicted deity over the rest of the pantheon. This pattern of choosing a deity and glorifying it as the ultimate godhead, while not denying the rest, is what Max Müller (1823–1900) and others identified as henotheism, for which the three heads would be an expression in Indian art.

Some interpretations given by Kirfel would identify the three heads with the three traditional stages of life (gunas: student, householder and ascetic), or the three stages of the sun: dawn, zenith, and dusk. The last one is linked to a reading of the Rigveda (I.XXII.16-17) where the god Vishnu is said to travel through the whole world in three steps. This could be related to his solar attributes in art as being the embodiment of an ancient hypothetical Rigvedic trinity composed of what Griffith calls the “threefold manifestation of light in the form of fire, lighting and sun” (Griffith, p. 12) and identified with the ancient gods Agni, Indra and Surya. The fire god Agni is also described as “the seven rayed, the triple headed” (Rigveda I.CXLVI.1).

But this is not an attribute restricted to the Devas (gods), the Asuras (titans) are also described as three headed as it is the case with the monstrous son of Tvashtar whose three heads where severed by Indra (Rigveda, X.VIII.8-9). Although at first the two categories of deities are almost interchangeable, the Asuras would be demonized in later literature, like the demon Trishira in the Ramayana, whose name literally means three headed.

It is through the Asuras that, according to Kirfel, three headed figures would have entered Buddhism, primarily Vajrayana, as protector deities and demons of many kinds. The pantheons of esoteric Buddhism are probably the most complex, both in concept and size, and a great deal of syncretism takes place at this point.

Another author to propose such daring thesis linking East and West would be the Lithuanian historian of art Jurgis Baltrusaitis (1908–1988) in his Fantastic Middle Ages (1955). In this book he explores possible eastern influences in gothic art through the silk road. And the historian of religion Raffaele Pettazzoni (1883–1959) would spearhead further development of the research on the three headed images of the Trinity and its pagan models, as it relates, of course, to its history in the West.

Despite these additional approaches to the subject I would say that no one has attempted such a daring, all-encompassing analysis of a motif as Kirfel does in the present book. Perhaps even, one could argue, Kirfel has been overly ambitious in his attempt.

The inclusion of African deities near the end of the book, on top of the many categories already included, seemingly refutes the previously stated hypothesis that this is an aspect restricted to Indo European cultures. All in all, it is hard to give a final and possibly overly one-dimensional judgement of the intention and execution of this tiny but dense, yet highly ambiguous post-war book.

Kirfel’s analysis of the three faced depictions of the Trinity is rather shallow in comparison to his chapters on Indian art. He concludes that the “three headed form appears as empty and devoid of content” (p. 185) in the Christian West. However, the wonderful corpus of images which he gathers has not been reproduced or analysed by later scholars as far as I am aware, and this by itself makes Die dreiköpfige Gottheit an interesting antique book of art. Leafing through its densely filled pages, one begins to wonder if many of these rare and humble pieces still exist today...

In the end, it might all come down to the following debate: whether images and symbols hold inherent meanings, whether they can thus be tied to certain identities, or whether they exist simply as artistic motifs that are being dressed in various veils of meaning as history unfolds. Although the title speaks of a three headed deity, at the end this being does not seem to be one, but many gods indeed.

Bibliography and related reading

Adolphe Napoleon Didron, Iconographie Chrétienne, Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1843: https://archive.org/details/iconographiechr00didr/page/n3/mode/2up

T.A. Gopinatha Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Madras: The Law Printing House, 1914: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.49423/page/n7/mode/2up

Willhelm Halbfass, India and Europe: An Essay in Understanding, Albany, NY: SUNY, 1988.

Ralph T.H. Griffith, The Hymns of the Rigveda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 2017.

Jurgis Baltrusaitis, Fantastic in the Middle Ages: Classical and Exotic Influences on Gothic Art, Boydell, 1999.

Raffaele Pettazzoni, Essays on the History of Religions, Leiden: Brill, 1954.

Raffaele Pettazzoni, “The Pagan Origins of the Three-Headed Representation of the Christian Trinity”, Journal of the Warburg & Courtauld Institutes, 9. London, 1946.