‘Mystai’ by Peter Mark Adams

Review: Peter Mark Adams, Mystai – Dancing out the Mysteries of Dionysos, London: Scarlet Imprint 2019, ISBN 978-1-912316-12-0

by Damon Zacharias Lycourinos

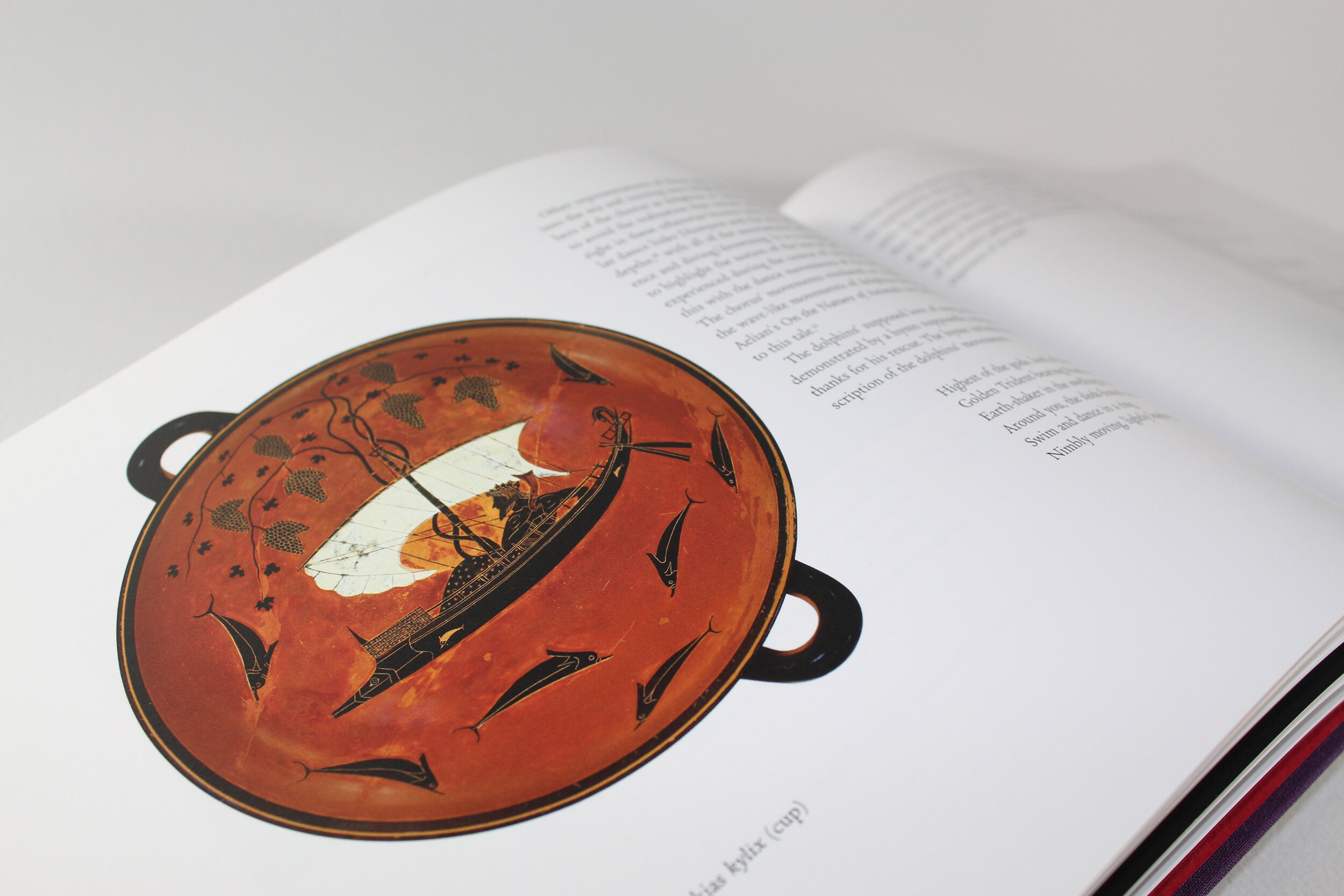

Mystai, a talismanic and beautifully illustrated tome published by Scarlet Imprint, is a textual and iconographic dreamlike journey into the Dionysian Mysteries. Peter Mark Adams, author of The Game of Saturn also published by Scarlet Imprint, channels an esoterically inclined reading of a Mystery Cult narrative depicted in the Dionysian themed frescoes of the Villa of the Mysteries once buried by Vesuvius just outside the walls of Pompeii and operative between 50 BCE and 79 CE. Adams begins by informing the reader that his intention is to interpret these primarily ritually-centred frescoes phenomenologically as a presupposed metaphysically and ontologically ritual worldview of the Dionysian Mysteries. Adams writes that the service of these Mysteries as higher forms of initiation is to “overcome the existential limitations attendant on mortality by transitioning the individual’s awareness, if only momentarily, to the contemplation of a higher order of being, one that transcends both life and death” (p. 3). More importantly, in relation to the Villa of Mysteries, Adams draws attention to the performative logic of ritual enactment of a gendered space revealed through movement and stillness, embodiment and transcendence, reflection and gaze.

The Narrative of the Mysteries

The first part of the book is an attempt to decipher the esoteric performative narrative of the frescoes by delving into the primordial and transgressively mythic constitution of Dionysos presiding over “life and death, man and woman, human and animal” (p. 8). The frescoes, Adams argues, point to an imagistic mode of religiosity based on the embodied mechanics of ritual prioritising personal experience within a time honoured tradition of metaphysical beliefs, symbols, and practices. In addition, immersed within this section of writing, a gem of perception is unveiled as a reminder to the reader that “only in the imaginal world do these deities appear with recognisable attributes, a nebulous personhood, but in themselves remain unknowable, more reasonably likened to the aura of an event, the quality of something that happens” (p. 9).

To instruct the reader further on the nature and function of the Dionysian Mysteries, Adams offers a rudimentary presentation on the structure and performance of the Mysteries in antiquity as secret and voluntary ‘higher rites of initiation’ providing a theurgic admittance to a specific deity. This initiation proceeded from the act of myesis (rite of purification) to cast away all miasma, leading to the orgia or telete (initiatory rite itself) to become epoptai (‘those who have seen’). Adams also provides a refreshing perspective on the significance of the Korybantic dance in the Dionysian Mysteries as a rite of purification stressing how important ritual purity was for the participants, and also draws a connection to the archaic magical practitioners attending the rites of the Great Mother known as Korybantes, and elsewhere as Kabeiroi, Dactyloi, and Telchines. Here Adams, like Jake Stratton-Kent, highlights the primordial foundations of chthonic and goetic origins of Greek magic and the Mysteries in antiquity. This is further reinforced with references to the initiates’ experience of undergoing Mystery rites, such as Apuleius, where one experiences death-like descent into the underworld followed by rebirth and ascent to the celestial realms to bear witness to an epiphany of the gods. In the endeavour to phenomenologically investigate this initiatory pattern Adams claims that this serves a technical purpose which the reader should refer to when introduced to the author’s understanding of the nature, structure, and purpose of the Villa of the Mysteries:

The cycle of descent and ascent is triggered by the collapse of the energetic supports of the persona, giving rise to feelings of deathlike dread; for it is only then that the source of one’s life energy – which is also the universal life energy – opens and surges to illuminate one’s awareness. (p. 28)

According to Adams, the key to the ritualisation of the participant to become a bakkhe, or one who has undergone the Dionysian Mysteries, is to consider the “psycho-energetic exfoliation of the intersubjective space” (p. 30) as providing a spatium for the purpose of the Mystery rite. In the Dionysian Mysteries the key to higher initiation, which Adams discusses with brief references to Hesiod, Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, Euripides, and segments of Dionysian myth, was the company of worshippers’ performance of the dithyramb involving a combination of hymn, choral dance, singing, and musical accompaniment, and the stellar chorus implicating the role of the Muses in the Dionysian Mysteries. In particular, and possibly under the spell of Alkistis Dimech, specific attention is drawn to the embodied transformation generated by the practice of dance that leads to sense of loss of bounded selfhood imaginatively and energetically exposing the dancing initiate to the energies of the symbolic structure of the rite. For the dithyramb this practice was defined by a threefold movement of strophe, antistrophe, and epode – movement counter clockwise, clockwise, and standing still.

The Villa of the Mysteries

The second part of the book presents the reader to the underlying historico-geographical background of the Dionysian Mysteries in Campagna. This is followed by a truly fascinating exploration of the socio-cultural and kinship organisation of the Dionysian thiasoi in Magna Grecia to construct a more precise depiction of who, why, and how the Dionysian Mysteries at the Villa of the Mysteries were enacted. As no primary information has remained, Adams draws from archaeological sources pertaining to other case studies of Dionysian thiasoi. In particular, attention is directed to another elite thiasos in Campagna revealing a fully functional Mystery organisation, with membership built upon the hierarchical socio-economic structures of Greco-Roman society, reflected through the nature and structure of the Mystery Cult, assisted by a whole industry dedicated to the maintenance and performance of the Dionysian Mysteries, and the need for certain element of Greek indigeneity to confirm a sense of genuine mystical religiosity.

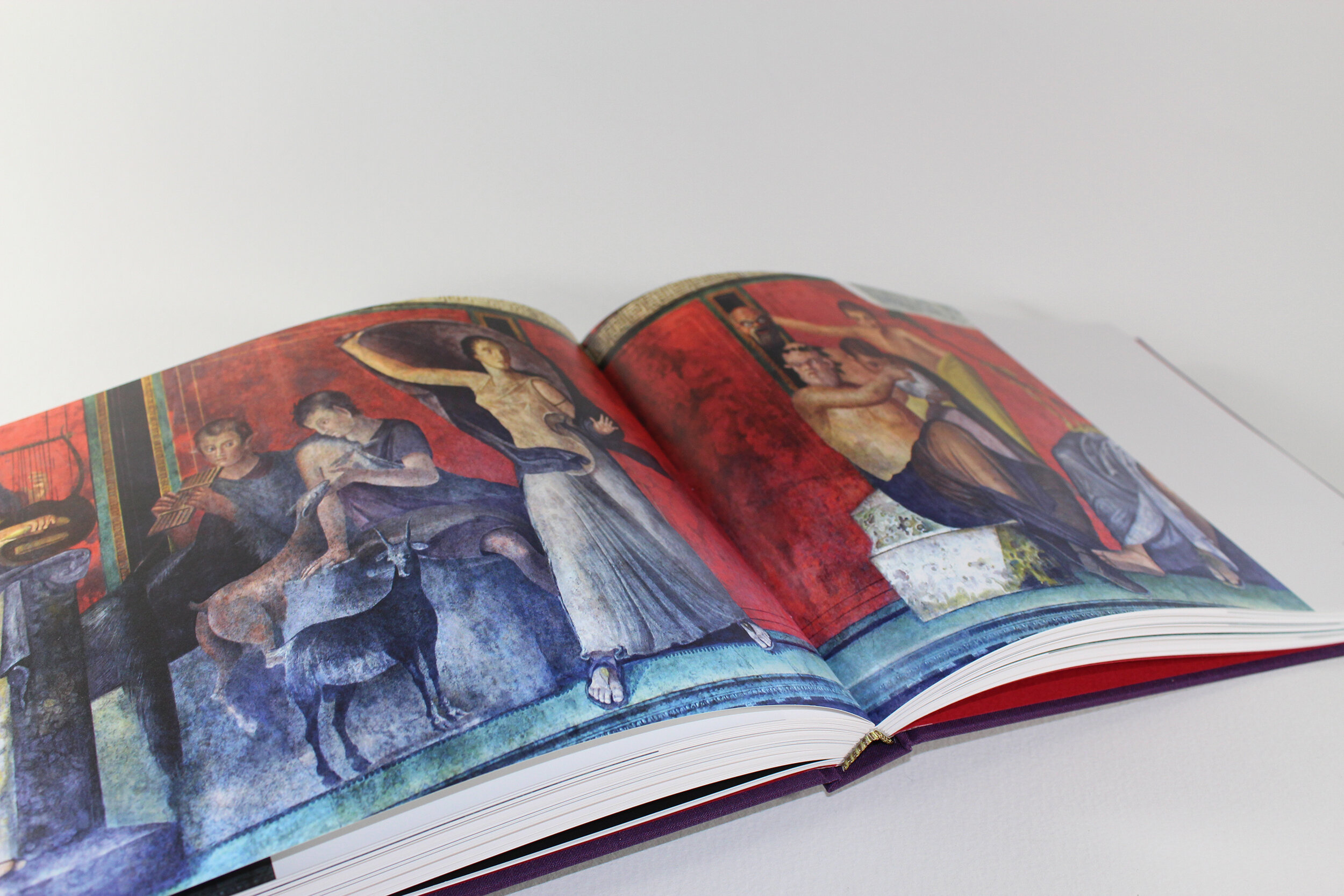

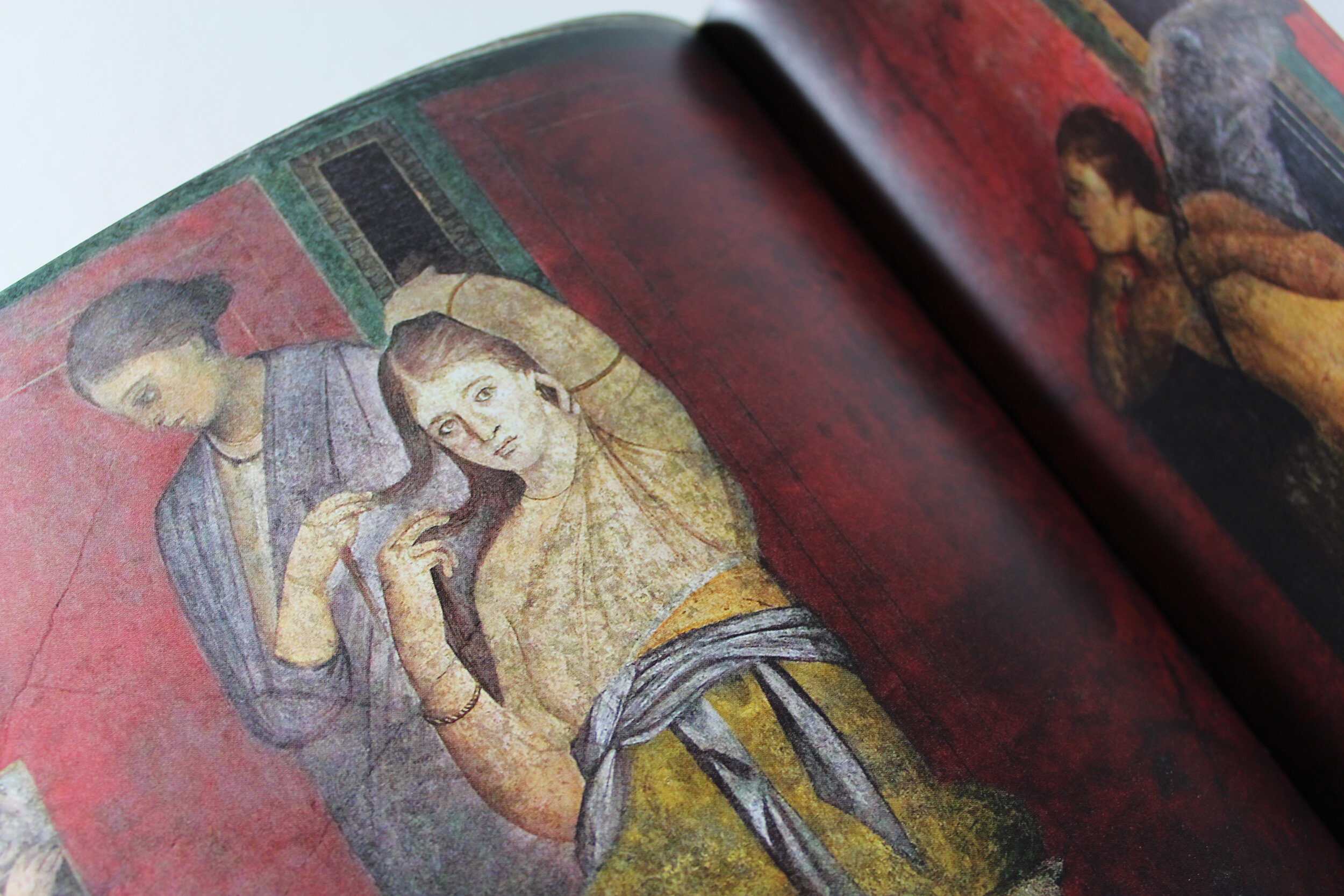

The third section of Mystai examines the uniqueness of the Villa of the Mysteries. Owned by a wealthy aristocratic family and devotees of Dionysos, the rooms where the Mysteries were enacted as indicated by the Dionysian themed frescoes were the antechamber (Room 4) and the main room (room 5), both of which demonstrate iconographic and decorative unity. Adams briefly recollects the gradual development of the artistry on the panels over time with each panel depicting Dionysian themes, events, and figures, along with possibly some of the members of the thiasos, all of which are women apart from a young boy reciting from a ritual text and thus casting a gendered space unlike any other in the context of the Mystery Cults. The other figures are Dionysos, possibly Ariadne, a priestess, a masked Korybantic dancer, chthonic mythological creatures, a winged deity, and two goats, all of which are in the style of megalographia and closely aligned with Dionysian iconography of the Graeco-Roman world. Each scene is a ritual narrative that overlaps with the previous and the following, with movement and stillness bringing the frescoes to life, the gaze of some of the figures captivating the observer and drawing them into an esoteric mythic worldview of the Dionysian Mysteries. However, as a form of sacred art, the frescoes remain loyal to the aporrheton (forbidden) and arrheton (unspeakable) of the Mysteries, subtly evoking rather than ultimately revealing during the nocturnal rites in the main room; lit by oil-wick lamps and torches, it would have cast an otherworldly spectre, climaxing with the core of the ritual – the invocation and possession of the deity.

To explicate the Dionysian themed frescoes, Adams constructs a theoretical structure for his esoterically inclined phenomenological methodology drawing on Jas Elsner’s notion of “ritually-inclined visuality” combining naturalistic representations, such as thiasos, that seeks to ritually interact with the observer. From this perspective, the frescoes can be decoded as a ‘liturgical rule book’ guiding the initiate to the ‘extraordinary experience’, to use Walter Burkert’s term, of the deific theophany and thus shifting awareness from an aesthetic reading to an instrumental one. Adams further develops his methodology by comparing and contrasting ‘doctrinal modes of religiosity’ with ‘imagistic modes of religiosity’. Based on the interaction of these two modes of religiosity Adams concludes that the Dionysian themed frescoes of the Villa of Mysteries are a codified set of doctrines and practices emphasising the path to an intersubjective embodied theurgic experience:

We can speculate that the frescoes served as a theatre of memory [… serving] as a mnemonic and instructional divide through which successive generations of bakkhai could be guided through the key movements, physical, mythical and phenomenological, that constituted the ritual process. (p. 74)

The tradition of decorating sacred spaces with sacred art, which for believers was deity-infused, served to instruct and intensify the ritual process and evoke intense emotional and spiritual responses. This mythically adorned sacred space Adams refers to as ‘heterotopic’, implying a space that distorts in unsettling ways to assist in “shift of awareness in the direction of the numinous realms to which the rites are directed” (p. 77). Referring to Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of ‘chronotope’, Adams argues that the temporal and spatial arrangements and illustrations of the frescoes, alternating between movement and stillness and transporting from the “contrasting worlds of representational realism and the timeless world of myth” (p. 79-80), deeply affect the participant’s shift from the profane to the numinous, from everyday reality to the non-temporal and non-spatial world of myth. Here the initiate bears witness to and embodies the extraordinary experience culminating with the “transformation of the psycho-energetic being of the initiate” (p. 80) and thus becoming a bakkhai. Adams ends by drawing attention to a unique and grasping feature of the frescoes – the exotopic female gaze where certain members of the thiasos have their gaze turned towards the main room seeking the gaze of the observer and luring them into the mythic ritual worldview of the Dionysian frescoes.

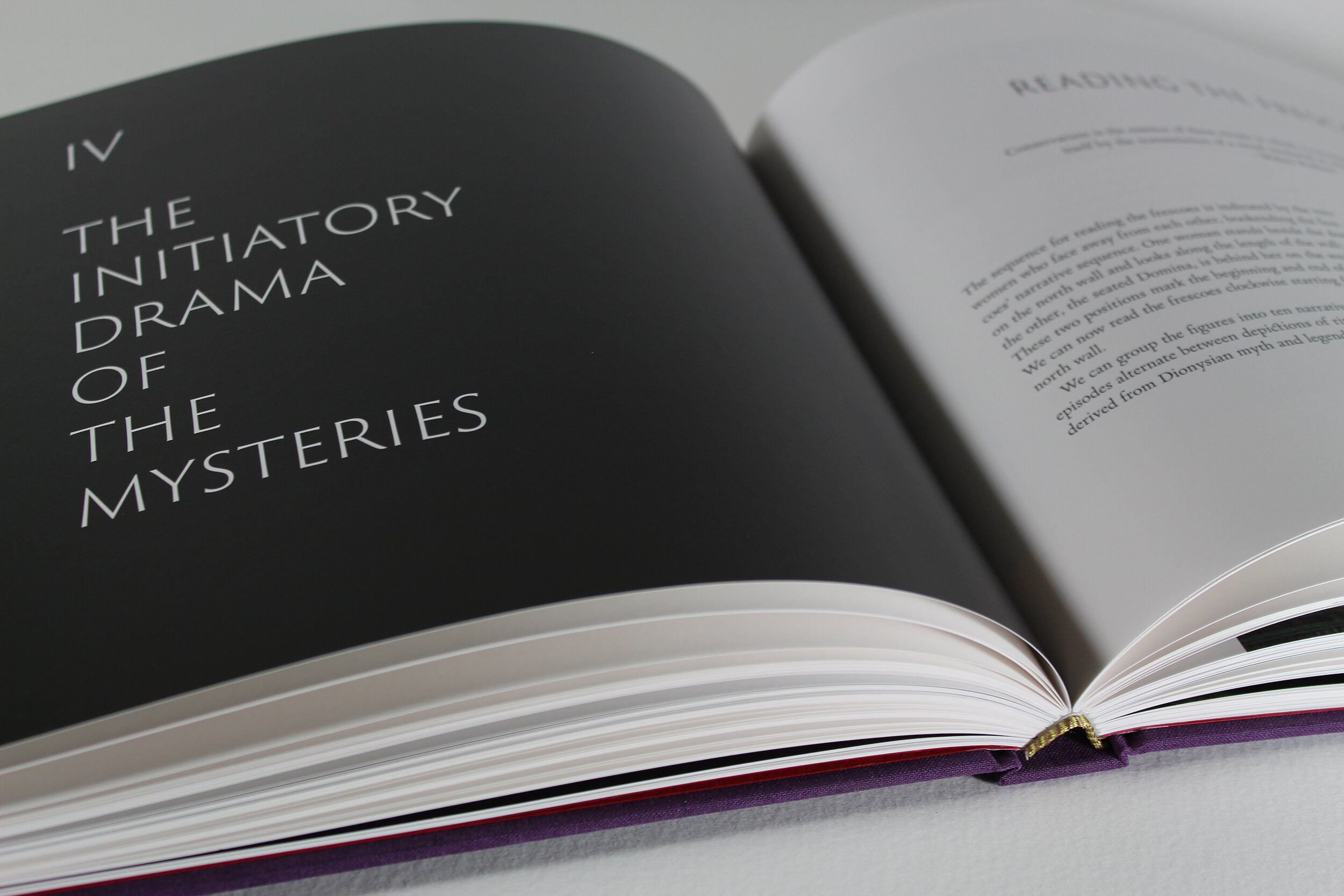

The Frescos

The fourth and final section of the book is a beautifully illustrated reading of the frescoes within the conceptual framework of the objective of the ritual to effect the possession of the initiate of the deity’s energeia. A brief discussion about the importance of the antechamber as a sacred space for preparation, oath-taking, changing into ritual dress is discussed before moving unto the main room. Adams’s methodology in this section consists of examining the events and figures wall by wall and panel by panel following a sequential ritual unfolding through iconographic symbol and gesture continuity of the liturgical rule book of the frescoes draped in manifesting Dionysian elements of appearance and colour in the same fashion that probably the original thiasos followed. This methodological approach is infused with a theoretical structure through discussion of a plethora of references to Dionysian myth and ritual in the endeavour to flesh out the initiatory dynamics and desired effects of each sequential panel. This in turn casts the aesthetic and symbolic reading as a mode of ritually inclined visuality seeking to create a chronotope to set the foundations for the extraordinary experience of initiation into the Villa of the Mysteries; for “theurgical union is only possible when the deity’s specific ‘feeling-tone’ – derived from the deity’s myth cycle, lore, ritual, and various representations – fully accords with that of the aspirant” (p. 125).

The north wall exhibits the preparatory events of the Mystery narrative with the first panel depicting a priestess and initiatrix of Dionysos overlooking the preparations and most likely the entire initiatory process. A young boy is shown reciting from a ritual text and a pregnant woman bearing a liba (a honey cake as offering) and sprig of green myrtle turns her gaze to the observer. Next, a ritual of purification takes place before the rural idyll encountering Silenos, nature spirits, and goats bathed in light purple haze signalling the immanence of deity. Finally, an alarmed woman appears seeking to remind the observer of the theophany to come symbolised by the hiera (the sacred objects of the cult) stored in the liknon (winnowing basket to separate pith from the chaff within which the Dionysian sacred objects were carried and presented).

The east wall, to which the alarmed woman is reacting, unveils the Korybantic scene again with Silenos proffering a deep bowl for young Dionysos to glare into and a mythic figure holding up a mask behind him. In the following, the observer witnesses the epiphany of the gods with a partly dressed Dionysos reclining in the lap of a maiden who is most likely Ariadne as protomystes (first of the earliest initiates). This scene serves as “the place-marker for a phenomenologically complex constellation of experiences connected with an immersion in a ‘ritually-centred visuality’” (p. 122). Next emerges the initiatory crux consisting of two standing figures, with one possibly being Lyssa whipping forth into the ritual narrative of the succeeding fresco Dionysian energeia (qualities of divine epiphany) to incur mania and frenzied possession. Also, kneeling is a woman with a liknon before her revealing what may be a herm-like statue of Dionysos.

The ritual act of Lyssa feeds into the south wall manifesting the moment of initiation as experienced by the initiand, followed by the robing of the initiate. The initiate is a dishevelled and disorientated kneeling woman resting her head in the lap of a woman comforting. The kneeling woman's state of being most likely overwhelmed by the possession of the energeia unleashed by Lyssa signals her reception into the Dionysian Mysteries through a series of ritual gestures. Behind the seated woman is another bearing the thyrsos over the initiate’s head as a ritual gesture connected with the influx of divine energeia.

Based on the initiate’s posture and bewildered expression, Adams speculates in reference to sexual elements of Dionysian myth that the act of ritualisation that the initiate has undergone could be “an act of anal penetration with an olisbos” (p. 141). At this point Adams ventures into a realm of hypothetical consideration of the presence and effect of entheogens in the Dionysian Mysteries, and in particular some form of fungal psychedelic. Adams supports this by widely drawing upon certain suggestive themes in Dionysian myth, certain symbolic representations depicted in the frescoes, the attested use of entheogens in other mystical and magical rites, and the deeply expansive effects of entheogens to accustom the psycho-somatic constitution of the participant for possession and epiphany. In regards to the kneeling initiate, Adams again speculates that probably the olisbos (dildo) might have served as an applicator for anally inserting the properly prepared entheogen for a faster delivery into the bloodstream. The south wall continues with the dance of the bakkhai where after receiving the divine energeia from Lyssa’s whiplash the initiate is carried away with enthousiasmos. The completion of the Mystery narrative confers the title of bakkhe upon the woman and with the epiphany of the god the title epoptes (‘one who sees’, title for one who has undergone the Mysteries and is repeating participation). The south wall ends with the robing of the bride and her gaze turned towards the main room “that halts the temporal flow of the action and throws our observer status back upon us” (p. 148). Gazing away from the mirror shown to her by Eros suggests that she as the bakkhe and epoptes is now firmly within her own being with the god rather than fragmented and scattered in reflections of mortality. The Mystery narrative ends with the west wall where the Domina resides in all her solemn and dominating splendour overseeing the iconographic performance of each and every fresco.

Conclusion

A meticulous study of this book will most likely feel like a daydream transporting the reader to the ancient world of the Mysteries and their gods initiated by Adams’s eloquent writing and personal insights supported by beautiful images of the frescoes of the Villa of the Mysteries and other ancient iconographies and artefacts. The functional combination of text and imagery is what makes Mystai such a potent and inspiring book. Adams is careful with his use of subject-specific terminology related to the Mysteries with the inclusion of an additional glossary. The book did cast a spell on me and inspired me to dream and seek to re-enact the Mysteries with more fervour, as it will probably do for any educated and esoterically-inclined reader with a passion for antiquity and willing to entertain an alternative and non-reductionist reading of the Dionysian Mystery Cult. The placement of the thematic sections and the flow of narrative provides a smooth reading experience where through text and imagery one may begin to imaginatively embody the Dionysian spirit. It is akin to observing a theatrical play and even participating in spirit, whilst also being provided a scroll containing the deciphered background story for each event to form a collective experience with the female protagonists of the Villa of the Mysteries and dance with the god and his mythic entourage.

Despite it being one of the most engaging books I have read this year, from a more rigorous academic viewpoint certain terms, themes, and ideas could have been explored and examined in more depth. For example, although concise and engaging, Adams could have gone deeper into the history, structure, and purpose of the Mysteries in antiquity in his opening section, thus providing an informed historical background for uninformed readers upon which he would set the foundations of his study. Also, although a significant part of his methodology, Adams does not provide a definitional line of reasoning for choosing phenomenology as a philosophical tool of investigation. A general discussion followed by a more specific analysis of the preferred phenomenological approach to be followed would have provided the reader with a point of theoretical reference for more critical insight into Adams’s conclusions. This appears to be the case at the start with his use of the term embodiment. However, as the reader may come to realise, the notion of embodiment develops poetically throughout the book, engaging the reader’s interest and intrigue. At this point, though, Adams’s thesis could have benefitted from examining various academic studies on the phenomenology of embodiment, and in particular embodied cognition, as a means of further deciphering the multi-layered causes and effects of the religious experience of being initiating into the Mysteries.

Beyond the academic ‘nit-picking’, this book is a gem and Scarlet Imprint have gone way and beyond to produce a truly evocative tome. I wholeheartedly recommend that those interested in the Mysteries, both in theory and practice, should indulge in Mystai seeking within every page an epiphany and a celebration of the great god Dionysos immersing oneself into the ritually-centred visuality of the Villa of the Mysteries to generate a beautiful and untamed constellation of theurgic experiences.