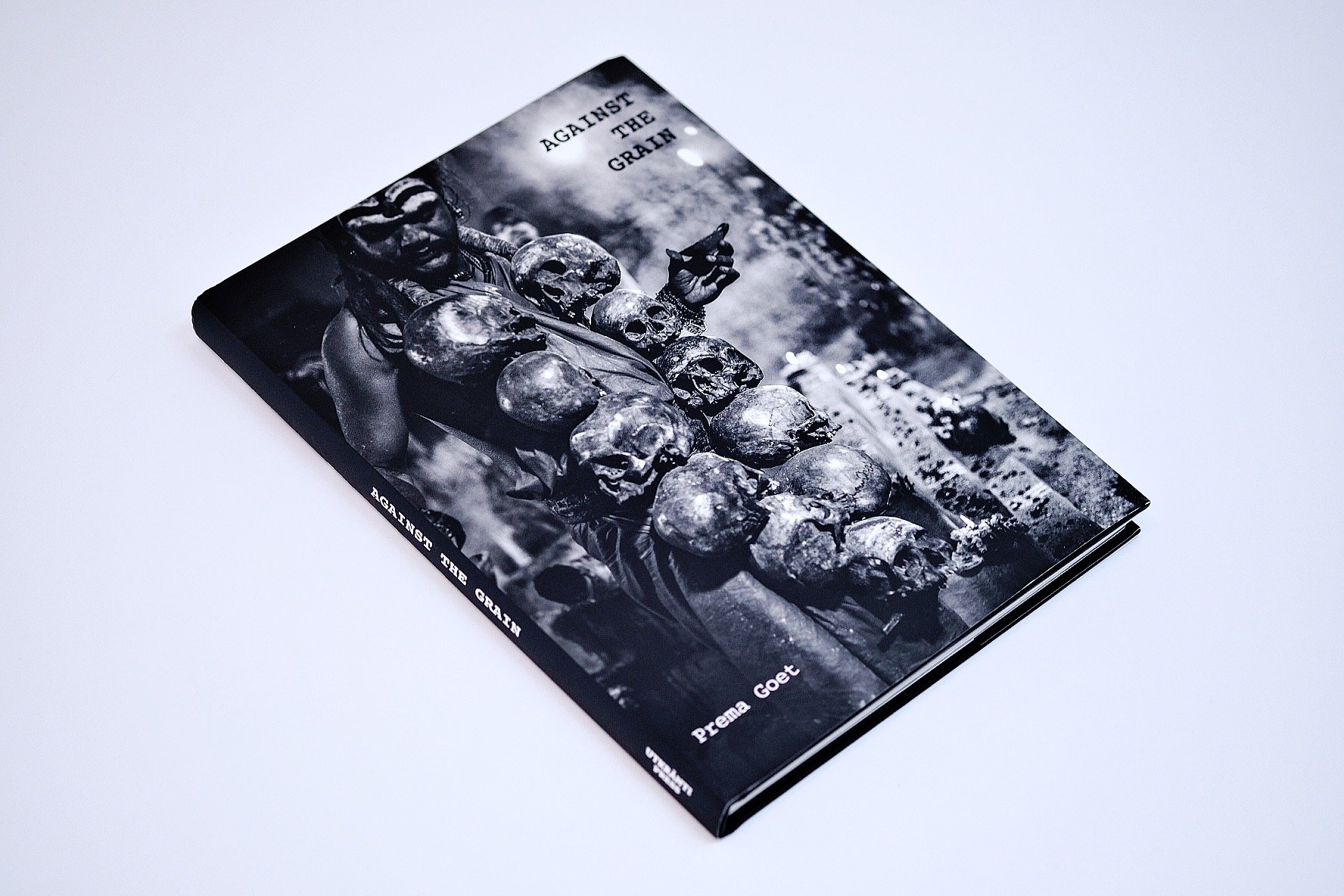

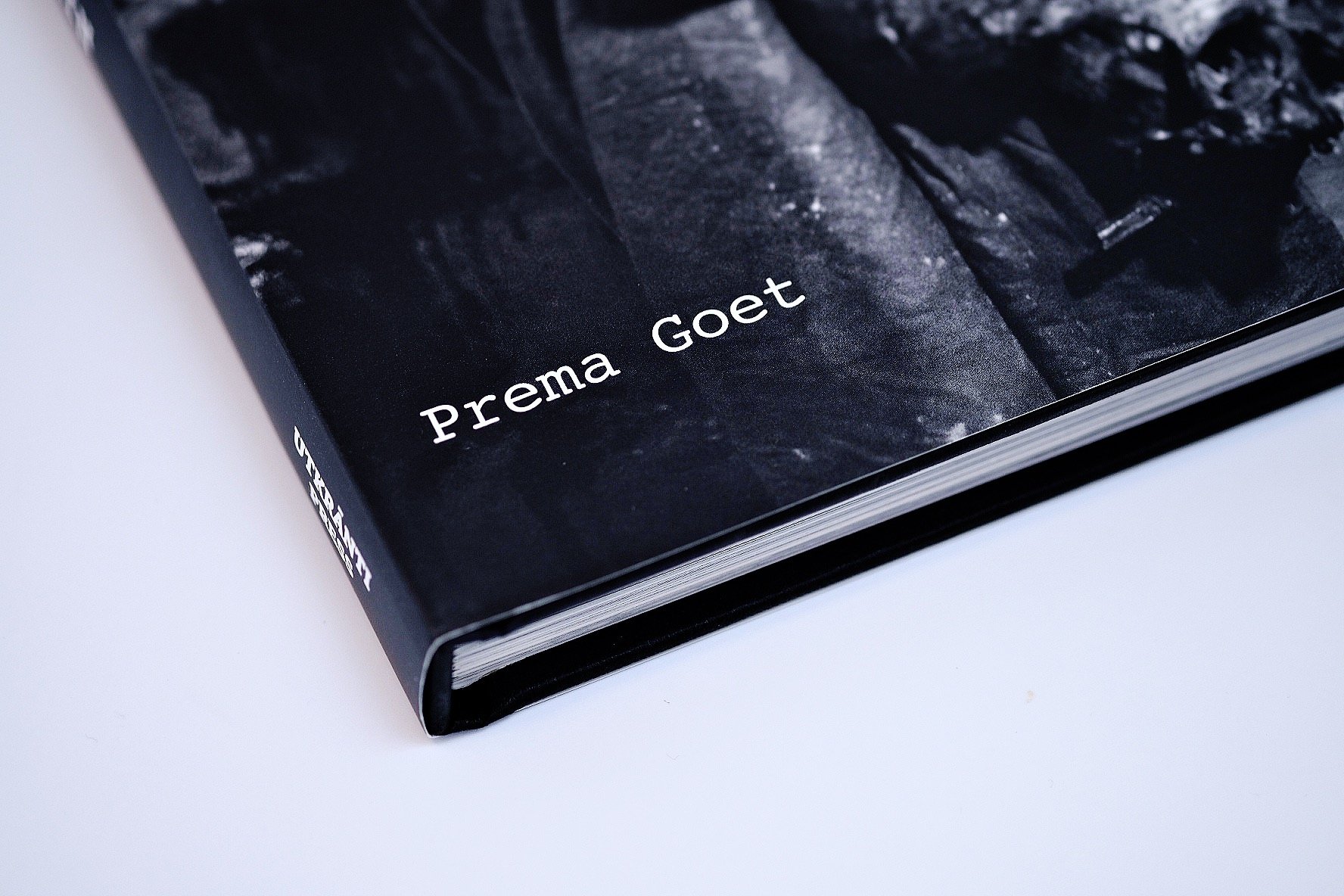

‘Against the Grain’ by Prema Goet

Review: Prema Goet, Against the Grain, London: Utkrānti Press, 2022, limited edition of 500

by Frater Acher

Prema Goet's Against the Grain is an intoxication inducing book.

The Grimm brothers in their German dictionary, published since 1851, knew how to interpret the word Rausch (Intoxication) from Middle High German (riuschen), where it originally meant an “impetuous movement”, an “impetuous attack”, “to rush”, or “to run up”. Intoxication thus denoted a state of being-attacked, a state where something other is breaking into that which just was.

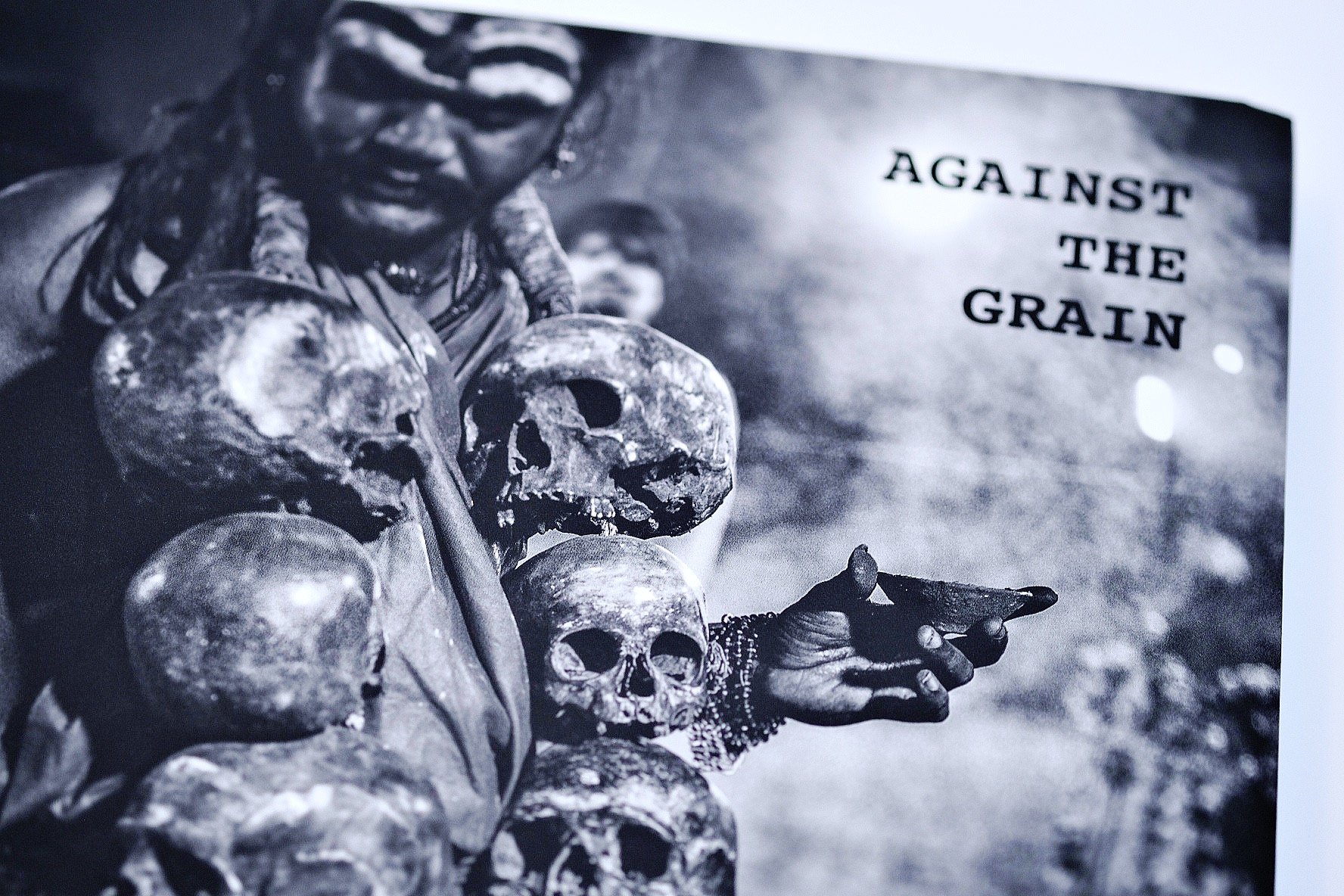

This is precisely the experience of the viewer when reading Goet's book. In fact, this work cannot really be read but we can allow ourselves to be entranced by it: by its black and white photographs, so sensually charged, so overflowing with the flickering lights of life and death that by the turn of the page they blur, like a circle drawn in dust, the line between here and there, between life and death, man and daemon.

Unquestionably, Against the Grain would have been a banned book in the past. For his masterfully shot images not only ask too many questions, but in themselves set too much in question.

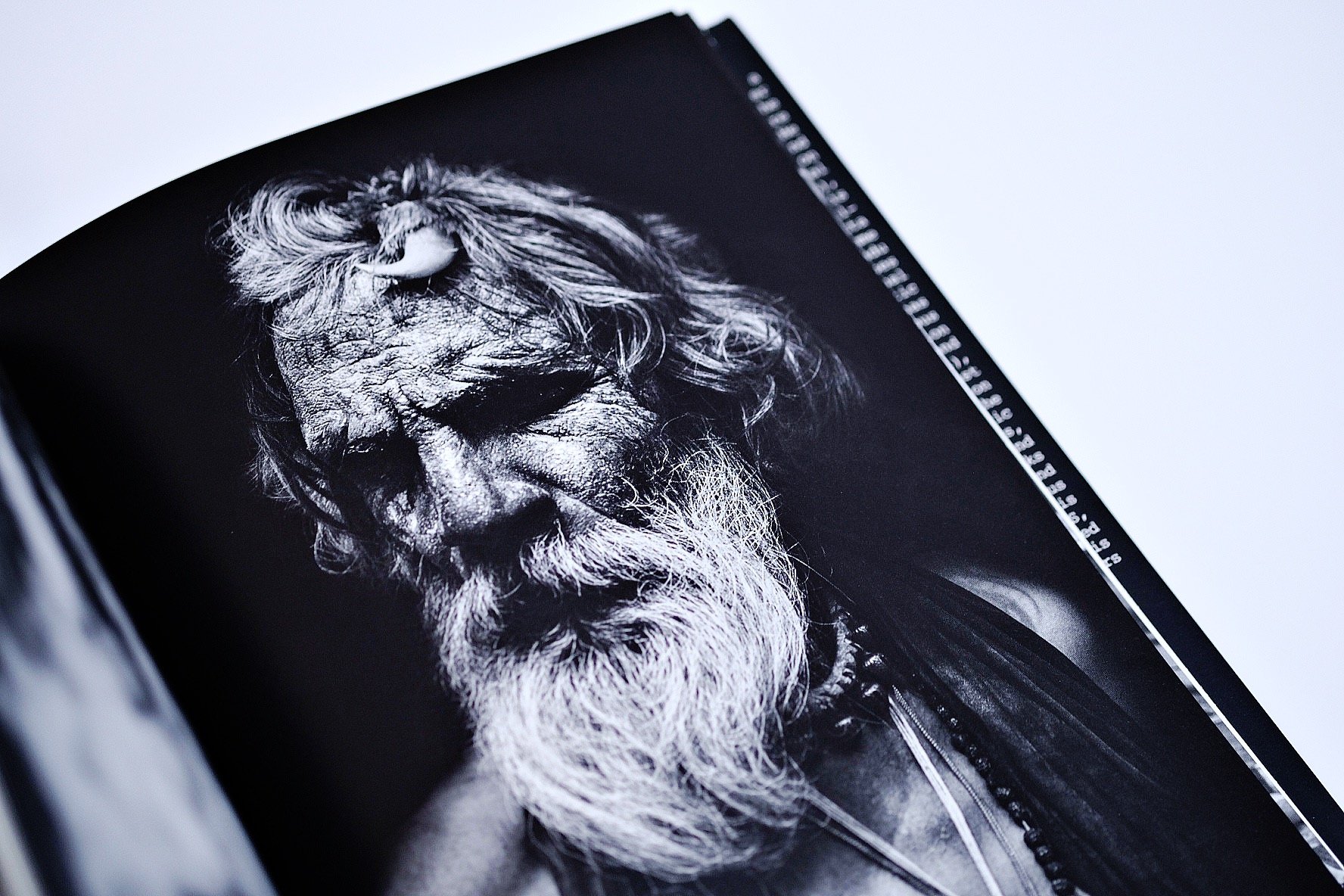

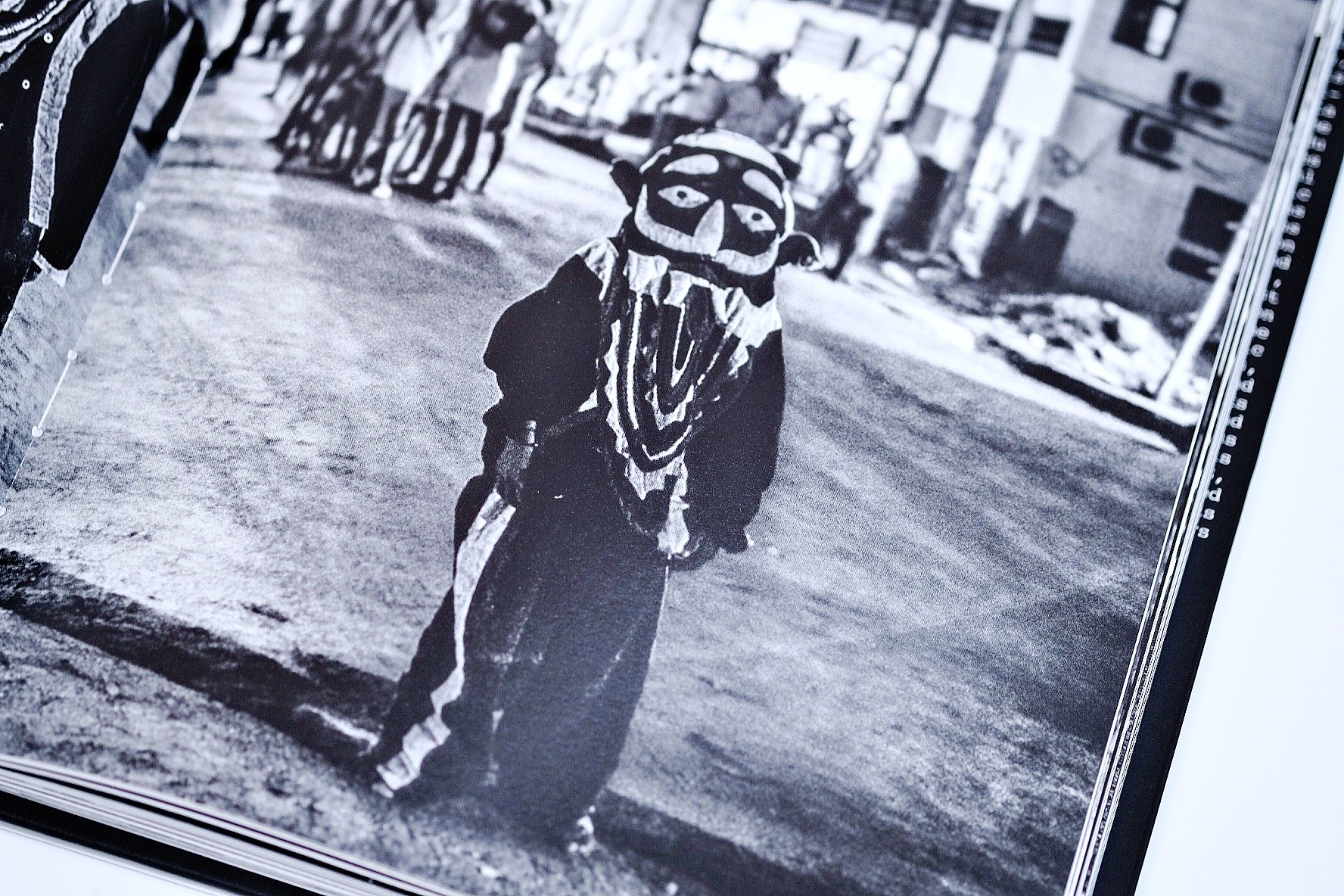

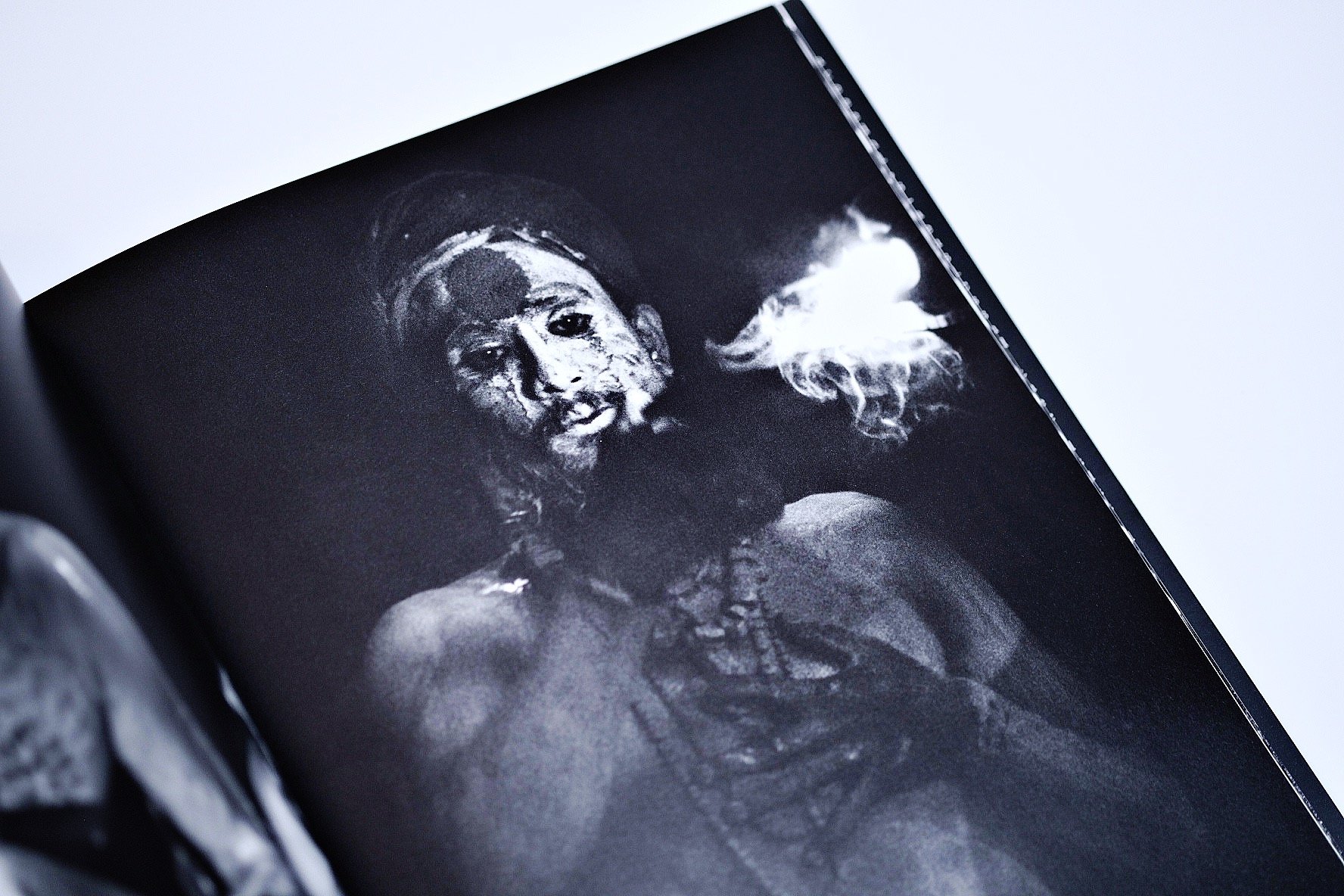

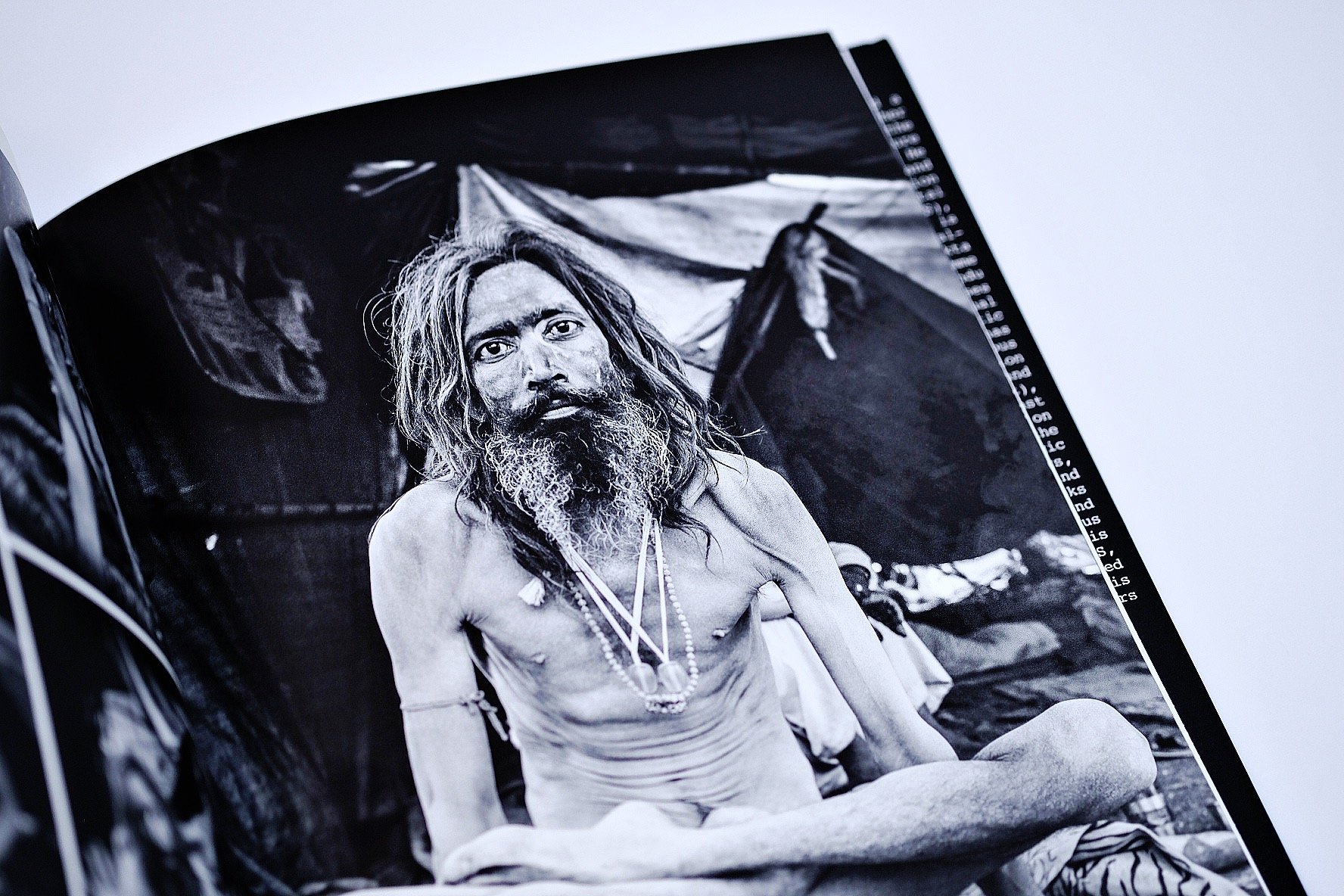

Against the Grain is a book about the left-hand path as it has survived on the Indian subcontinent until now. In radical participant observation, Prema Goet allows us to mingle for fractions of moments with aghoris, wandering sadhus, and the tumultuous celebrations of various festivals. Not only the willingness to, but the spiritual quest to cross borders jumps out at the viewer from every angle of this book. And yet, it is precisely the tension with the Western viewer’s own values, norms and conceptions of the world that this book is not about. In Goet’s pictures, what is beyond the taboo does not congeal into an exotic Other, into a projection surface of one’s own objects of condemnation or shameful longing. Rather, the young photographer manages to reveal the Other to the viewer in its own autochthonous life. The strangeness remains, but it peers out and shines from the shadows of each photo as a corporeal “You” and not as a distorted “It”.

For example, we see ascetics of the Vaishnava sect sitting on raw earth, in a circle scratched into the ground, surrounded by patties of burning cow dung, their bodies smeared with ashes, their wild hair tied into a wreath. From the picture we are met by a Stoic calm, a composure that seems to be anchored not in the knowledge of order and meaning but in the acceptance of disorder and the constant breaking and shattering of meaning. Then we turn the page and see two of the ascetics exchanging a word, seemingly as commonplace, accompanied by a smile, as two neighbours in the suburbs talking over the garden fence. The human always remains in focus in Goet’s pictures, even if it reveals its rhizomatic relation with the seemingly inhumanly filthy, wild, dead, and dark.

Goet’s book encompasses images of five different thematic complexes which the author introduces, tightly summarised, on seven densely printed pages. This introduction is recommended to be read not only attentively but preferably multiple times. In stylistically similar elegance to his black-and-white photographs, Goet knows how to break up the image-worlds of the following pages for the Western viewer in concise sentences. Through his introduction, stripes of light of a deeper understanding fall on the radical physicality of his pictures, which make the afore mentioned “you” even more tangible to the viewer and counteract the hazard of exotifying these intoxicating images.

Thus, Goet summarises a particularly impressive series of images of the 18-year ritual of some ascetics of the Sampradāya order with the following words.

However, despite all the performative variations, with various asanas also performed at the end of the practice, there is a consistent pattern of ritual acts at the beginning of the practice this aims at consecrating the area of the tapasyā and at “calling on” deities through several mudrās. Furthermore, the bhutaśuddhi (a bodily purification through the process of nyāsa whereby the mental deconstruction of one's physical body and the re-construction of it into a cosmic one) is defied by the relationship of subject and object through mantras and visualisations.

In this system, mantras are living entities which can shield (kavaca) and command the population of spirit entities which resides within one's body. This may have inconsistent patterns, as this is dependent on various factors such as the types of sadhana practiced, the disciplic lineage one may come from or simply on one's spiritual inclinations. [s.p.]

Much of this invites us to meditate about body conceptions in Western magic and on parallels and/or break-lines we find thereby. E.g. I for one, tend to muse on the idea of inner astrology represented by Paracelsus according to which the human body is composed not metaphorically but quite palpably of the animated organ cells of the Olympic spirits.

Such comparisons should not, of course, lead us to idle speculations about any presumptive lines of tradition from the Indian subcontinent to Paracelsian itinerancy in 16th century Europe. Rather, the deliberate oscillation between the daemonically charged imagery Goet presents here and our own magical reality offers the prospect of a far greater gain: namely, the possibility of seeing ourselves and our own magical practices in a new light. By exploring and engaging with the strangeness in Against the Grain, and seeing it infused throughout with its own humanity, we may return our gaze to the mirror and recognise the very same daemonic traits, if only dormant, within ourselves. As I have already pointed out, this is an intoxication-inducing book.

In this short, yet mostly visual, presentation of human ritualia I propose introducing the viewers of Against the Grain to the subjects of my investigations, thereby disclosing the material cultures embedded in each of the images herein. And since, to some, the theoretical study of esoteric practices, particularly the more obscure ones, cannot be entirely and adequately analysed by rational means, I suggest that one must first immerse oneself in the irrational thought and experiences provided by religion for only then can one begin to make some sense of certain things. To this, I must add that my primary concern here is purely based on the representation of performative practices through the medium of multi-modal ethnographic undertakings and not on any of the other branches of human and social sciences such as philosophy, linguistics, history and the like. [s.p.]

Fritz Perls lent us the wonderful aphorism: Lose your mind and come to your senses. Perls also knew that the printed word or picture is a poor medium to initiate such experience. Still, I think Perls would have liked Prema Goet's new book very much. For it deliberately places itself at that far edge of the known book world where we are not stimulated to commentary and discourse, but to silence, to sinking-in and to experience.

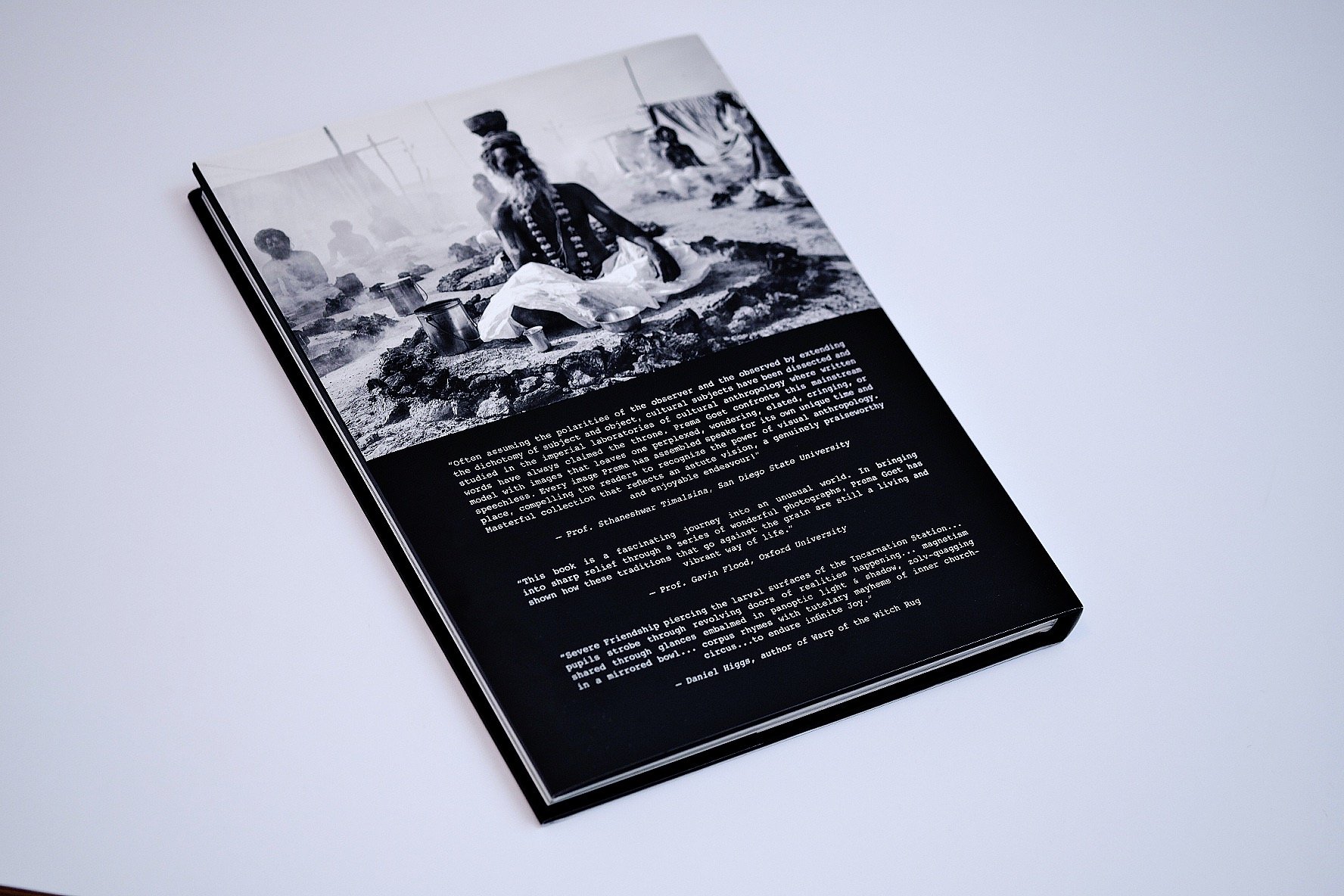

Finally, it should be mentioned how stunning the production quality of the book itself is. Self-published, the heavy paper feels good in the hand, prevents the photographs from showing through when backlit, and the shades of grey and black shine in rich depth. The font appears in typewriter-style monospace, the pages are deliberately left bare of any page numbers, and in its two solid columns the text has a monolithic quality. In all elements the design of the book reflects the radical nature of its subject. It succeeds in dancing on the same blade as the images it contains: the antinomian crossing of boundaries never becomes an end in itself but points to a path all its own.

I strongly recommend the devouring of this book here, and a warning of side effects may also seem in order. What we hold in our hands here is immensely valuable from multiple perspectives. From the modern goês’ vantage point, Prema Goet offers us a veritable anti-grimoire. A book that contains no grammar, but pure visual poetry. Or, as it is put on the book’s back cover much more eloquently:

Severe Friendship piercing the larval surfaces of the Incarnation Station... pupils strobe through revolving doors of realities happening... magnetism shared through glances embalmed in panoptic light & shadow, zolv-quagging in a mirrored bowl... corpus rhymes with tutelary mayhems of inner church-circus... to endure infinite Joy. [Daniel Higgs, author of Warp of the Witch Rug, quote from the back cover of the book]