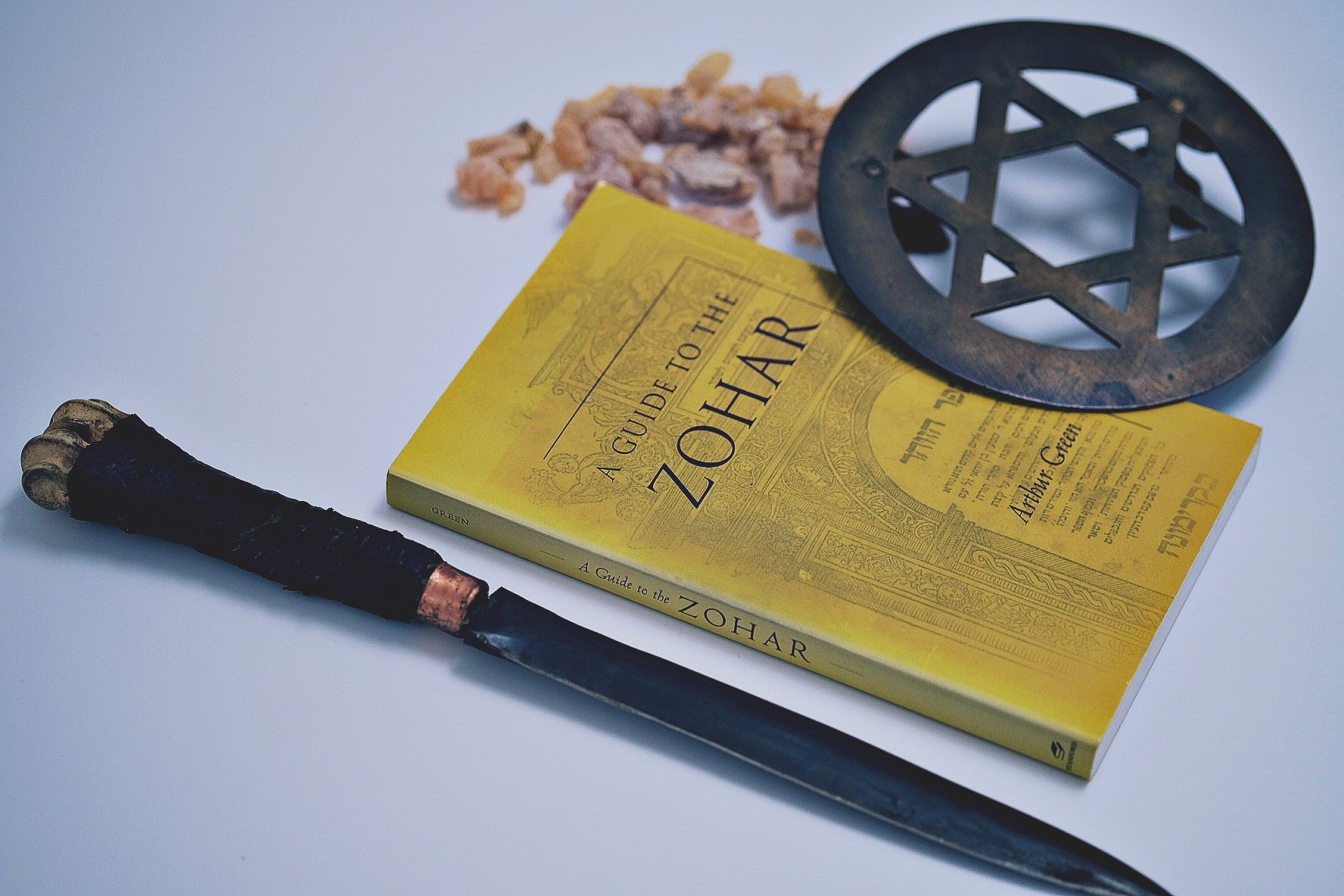

‘A Guide to the Zohar’ by Arthur Green

Book Review: Arthur Green, A Guide To The Zohar, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004

by Frater Acher

Overview

Arthur Green’s A Guide To The Zohar certainly is a compelling and will be, for many, a groundbreaking read. The latter certainly is true for a readership that has grown up with notions of Kabbalah shaped less by authentic Jewish sources than by the adoption of Kabbalistic techniques and concepts as found in Western magic since the 16th century. However, even for readers familiar with authentic Jewish sources – up to and including the modern works of Gershom Scholem and Moshe Idel – Green’s book offers not only a profound and succinct read but one that might border on the heretical.

Green is Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies at Brandeis University and one of the most prominent scholars of Jewish mysticism and Neo-Hasidic theology. His Guide To The Zohar was released in 2004 as a companion book to the long-awaited publication of the Pritzker Edition of the Zohar under the editorial direction of Daniel C. Matt.

Upon opening the book, and looking at the content section, we already gain a glimpse of Green’s refreshing approach to his subject. Chapters that view the Zohar from a historical relativist perspective alternate with passages that illuminate the emic or inner perspective – one of mystical experience of the Godhead in its bewildering rhizomatic splendour as well as its nebulous, distant, unknown singularity.

Over the first hundred pages and then again in the final sections of the book, Green traces the genesis of the Zoharic corpus of texts and offers fascinating insights into its manifold historical, spiritual, and cultural influences. In particular, here the reader begins to see the fine line on which its authors attempted to balance. This was a line between orthodox value conservatism and the need to present the mystical presence, mythic depth and intellectual appeal of spiritual Judaism in a new light.

Touched by Divinity and Its Own Time

According to Green, the Zohar should therefore be read not only as a breathtakingly comprehensive expression of the rich Jewish mystical tradition of 13th century Spain. Beyond that, it also represents a response to the worldly circumstances in the years of its writing, an exchange with the reality of life of the Castilian Jews in the 13th century. It thus conveys not only deep esoteric wisdom, but also – mostly interwoven and veiled in metaphors – the traits and threats of its time: the indignant rejection of an enlightened philosophical Judaism, the reactions to the threat of Muslim polemics and omnipresent Christian censors, and an innovative integration of Neoplatonic and Aristotelian frameworks as foundation for its own mystical cosmology (p. 9-10, p. 20-22).

Of particular importance because far less well known in Western, non-Jewish circles, is the narrative form in which the Zohar presents itself. In only a few chapters, Green breaks open the enigmatic work and allows insights into its deliberately constructed form: the recourse to the already mythical person of Simon ben Yochai from the Tannaitic period (2nd CE), the deliberate choice of Aramaic as a completely uncommon written language even amongst Jews at that time, and the group of unnamed mystics who met in small nightly circles, hidden in Castilian gardens, and who practiced their mystical exegesis of the Torah in a language foreign to themselves under strict secrecy into the early hours of dawn.

Without suggesting one-dimensional conclusions, Green points out e.g. the relatability of the image of Simon ben Yochai and his rabbinic students to the figure of Jesus Christ and his disciples. He explains the poetic and instrumental importance of Aramaic and how it rendered both the text itself and the flow of reading in an exotic-mythical splendour. And with astonishing clarity he points out the tension between revulsion and admiration in which the Jewish mystics must have found themselves vis-à-vis the flourishing monastic life of the Christian orders of their day.

Green expands on the latter point in his chapter on historical influences on the Zohar. Above all, his account of the development of the Shekhinah under the impression of and in constant confrontation with the erotically saturated cult of the Virgin Mary in 13th century Spain and France is to be emphasized here. Green succinctly explains how the Song of Solomon was transformed from a collective declaration of love between God and the people of Israel into a personal-romantic frame of reference. On the Christian side, such erotic-sensual reinterpretation of the Song of Songs was facilitated by Bernard of Clairvaux, amongst others. Here, the Christian celibate mystic now took the female role of the bride in the framework of a renewed Hieros Gamos tradition.

Since Judaism did not know celibacy, their male mystics found it difficult to identify with a female role vis-à-vis Divinity. That is, a female intermediary figure between the deity and the tzaddiq was essential to equally open the erotic relatability of the divine embrace.

Where did the Jews get this idea of a female intermediary between themselves and God above? It seems quite likely that this is a Jewish adaptation of the cult of the Virgin Mary, very much revived in the Western Church of the twelfth century, especially in France and Spain. Marian piety permeated the culture of Western Europe in this age: the dedication of cathedrals to the Virgin, roadside shrines, passion dramas, music, and art of all forms glorified her role. The Jews surely witnessed this and must have found themselves of two minds about it. On the one hand it would have confirmed their worst impressions of Christianity as pagan, idolatrous, and polytheistic. But there was also something beautiful and tender about the religious life associated with it that could not be ignored. The Jews, whose culture knew no glorification of virginity or celibacy, adapted the notion of a female object of worship to suit their own needs. The notion that there is a divine (or quasi-divine) female presence poised at the entrance to the divine realm, one who loves her children, suffers with them, and accepts their prayers to be brought before the throne of God, is shared by the Marian and kabbalistic traditions. Most likely the latter, which developed in the century following the great Marian revival, is derivative of the former. (p. 95)

In Greene’s account, it was precisely these momentary flashes, in which even the Jewish mystic might have felt enticed in an almost heretical way by alien ideas, that provoked the publication of the Zohar in its present form. These flashes can be found, on the one hand, in the tense relationship of Judaism to Christian and Muslim spirituality. Yet, on the other hand, they can also be detected within the Jewish communities themselves, where a rather rationalistic philosophical mindset continued to spread in the aftermath of Maimonides’ groundbreaking writings. (p. 21)

[…] the authors of the Zohar set out to create a Judaism of renewed mythic power and old-new symbolic forms. Far from being crypto-Christians, they sought to create a more compelling Jewish myth, one that would fortify Jews in resisting Christianity. (p. 95)

I emphasize this aspect of the Zohar’s genesis here as it’s likely unexpected to many readers of modern Western Magic. The much more familiar narrative is that of the hostile appropriation of Jewish mysticism by Christian Kabbalists during the Italian and German Renaissance.

If we follow Greene’s account, however, this is not an either/or story, but one of and/also. Where one-dimensional historical accounts of power relations, influences, and cultural points of contact are readily applicable, Greene encourages us to explore a web woven of nodes and echoes – without ever glossing over the dominant hostility and open aggression exerted by Christian rulers against 13th century Jewry.

As such, it has to be emphasized that it would be distorted to present the Zohar as a predominantly defensive text. Already from the etic outsider’s perspective, as this reviewer holds it, the Zohar’s undying appeal and striking influence on Western Mysticism and Magic since the time of Guillaume Postel (1510-1581) is proof enough of the intellectual, mystical, and mythological brilliance of this seminal voluminous corpus of texts.

A Text Turned Mystical Tool

The middle section of Greene’s book then elucidates on eight key themes of the Zoharic text canon. In an impressive combination of historical acuity and empathy for the mystical process, Greene manages to cover a lot of ground here in chapters that are less than 10 pages each. The perspective he offers ranges from kabbalistic cosmology and the topos of primordial evil, to the Torah and its commandments, all the way to aspects of lived reality such as the concept of avodah, the tzaddiq and the relation of the Zohar to the Jewish people in exile.

We would get lost in individual aspects if I tried to map the variety of insights Greene brings together here. Suffice to say he accomplishes what he sets out in the preface to do: To “treat some key themes within the Zohar, examining its techniques, without, hopefully, reducing them to the object of mere ‘intellectual history’” (xiii).

From the variety of topics touched upon it becomes all the more clear what Green emphasizes right at the beginning of his book, namely that the Zoharic writings rest on the broad foundation of five different elements (p. 10-13):

The haggadah or narrative tradition of the Talmud and various works of Midrash,

the halakhah, the legal and normative body of works, and the centre of attention for the majority of Jews “throughout the medieval area” (p. 11),

the liturgic tradition as in the literary gerne of the texts recited in prayer, worship and spiritual poetry (technically a subset of halakhah), and of particular relevance to Kabbalists in relation to the notion of kavvanah or inner purpose and meaning of a prayer,

the Merkavah tradition, known in Medieval times from fragmentary treatises circulating among mystical communities across the continent, as well as direct references in the Talmud,

and finally, the Jewish speculative-magical tradition, which “is the hardest to define” (p. 13) as the extant corpus of writings is highly scattered, often contains contradictory elements, and currently still remains best illustrated “through the litte book called Sefer Yetsirah” (p. 13).

Kabbalah must be seen as a dynamic mix of these five elements, with one or another sometimes dominating. It was especially the first and last elements – the aggadic-mythical element and the abstract-speculative-magical tradition – that seemed to vie for the leading role in forging the emerging kabbalistic way of thought. (p. 14)

The resulting corpus of Zoharic writings, especially in its original Aramaic form – which would have forced even the learned Jews of his time to read slowly, rhythmically, and would have emphasised even more the often recurring idioms and neologisms (p. 170-171) – was precisely not to be understood as a linear propaganda writing for a revival of Jewish mysticism. Quite the opposite: similarly to its predecessor, the Sefer Bahir, so also the purpose of the Zoharic corpus was to deliberately enchant its students.

[…] the purpose of the book is precisely to mystify rather than to make anything “clear” in the ordinary sense. Here the way to clarity is to discover the mysterious. The reader is being taught to recognise how much there is that he doesn’t know, how filled Scripture is with seemingly impenetrable secrets. “You think you know the meaning of this verse?” says the Bahir to its reader. “Here is an interpretation that will throw you on your ear and show you that you understand nothing of it at all.” (p. 18)

The skilful play with overlapping and sometimes contradictory interpretations of text passages, the depth and complexity of the Pardes (פרד"ס) method of biblical exegesis as proposed by Moses de Leon, the overwhelming multifacetedness that any reader of the Zohar is confronted with – all of this was deliberately designed to knock the intellectual mind off centre and draw one’s understanding closer to a mystical experience as such. The Zohar, thus, is a most radical work, pushing the boundary between a literary artefact and an applied mystical tool.

Insert: For practicing magicians in the West, such radical notion of the capabilities of a text should be a reason to pause. And in that pause we might want to reconsider where to take the grimoire tradition next, and why the segregation of textual elements into theory and practice might be hugely problematic and indeed constraining…

The Zohar Turned Flesh

Finally, we would like to highlight the powerful liberating blow – at least for this reviewer – that Green's explanations of the process of creation and the inner structure of the Zohar represent. This is especially evident where he addresses both the organic and the deeply erotic aspects of the Zohar.

Since the influence of Ramon Llull (c. 1232-1315), Johannes Reuchlin (1455-1522), and Agrippa of Nettesheim (1486-1535), to name a few, a highly technical understanding of (Christian) Kabbala has prevailed in Western mystical and magical circles. Comparable to the technical-mathematical astrological arts, the kabbalistic techniques of notarikon, gematria, and temurah, of Abulafic letter-combinations, or the complex assignment of letters to paths and gates occupied the foreground of students of Practical Kabbalah.

The excessive focus on these techniques comes as no surprise, since the oral tradition – the very core of Kabbalah – broke off with the transition to Christian Kabbalistic writings. What remained, what survived the cultural appropriation, were those things that could be put down on paper in black and white, that corresponded to the logical demands of the emerging academic sciences – and precisely not the mystifying, often paradoxical nuances and facets of the actual Zoharic writings.

Despite the huge amount of original Kabbalistic writings that have become available in English over the past thirty years, little has changed in the conservative milieu of many Western Magical traditions. That’s why even for the modern student of Practical Kabbalah, as it has been preserved outside the Jewish Tradition, it might be perplexing to recall this simple insight: that the most essential instrument of the Kabbalists was neither the Tree of Life, nor highly complex combinations of letters, but genuinely understood and enlivened eros and ecstasy.

Especially, in regard to the Castilian kabbalistic circles from which the Zohar initially emerged, Green highlights the following:

The Castilians’ depictions of the upper universe are highly colorful, sometimes even earthy. The fascination with both the demonic and the sexual that characterizes their work lent to Kabbalah a dangerous and close-to-forbidden edge that undoubtedly served to make it more attractive, both in its own day and throughout later generations. (p. 26)

It was within this circle that fragments of a more highly poetic composition, written mostly in lofty and mysterious Aramaic rather than in Hebrew, first began to circulate. These fragments, composed within one or two generations but edited over the course of the following century and a half, are known to the world as the Zohar. (p. 27)

Not just connectedness, but rootedness in organic nature and its living experience was a central element of these 13th century Castilian mystics.

Thus, the experience of the cosmos was seen as essentially rhizomatic i.e. everything was directly connected to everything else. Paths led not only from here to there, but from here to everywhere. This meant, for example, that the ten sefirot could be placed on a spatial or temporal axis of the Neoplatonic emanation model, and yet they all emerged simultaneously in interpenetration, coexistence, and overlap (p. 35). Nature, like the Godhead, was not viewed as a logical key-lock enigma, but as a pleroma (p. 33) i.e. a fullness that a human heart and mind can only tangentially grasp while immersed in ecstasy.

The Kabbalah of the Zohar, thus, was not only a tradition of mystical exegesis, but much more importantly a textual-divine vehicle to achieve “a cosmic spirituality” (p. 58).

[…] to speak of the sefirot is not simply to draw on a body of esoteric knowledge, but rather to enter the inner universe where sefirotic language is the guide to measured experience. (p. 78)

Since it also was a purely male tradition, this accordingly rubbed off on the demonisation and mystification of the female aspects of nature.

While Malkhut receives the flow of all the upper sefirot from Yesod, She has a special affinity for the left side [i.e. sitra ahara, the realm of the demonic]. For this reason She is sometimes called “the gentle aspect of judgment,” although several Zohar passages paint her in portraits of seemingly ruthless vengeance in punishing the wicked. A most complicated picture of femininity appears in the Zohar, ranging from the most highly romanticized to the most frightening and bizarre. (p. 50)

She [i.e. Malkuth] is tragically exiled, distanced from Her divine Spouse. Sometimes She is seen to be either seduced or taken captive by the evil hosts of sitra ahara; then God and the righteous below must join forces in order to liberate Her. The great drama of religious life, according to the Kabbalists, is that of protecting Shekhinah from the forces of evil and joining Her to the holy Bridegroom, who ever awaits Her. Here one can see how medieval Jews adapted the values of chivalry – the rescue of the maiden from the clutches of evil – to fit their own spiritual context. (p. 51)

As much as chivalric values were used to illustrate the moral qualities of the tzaddiq, these passages do not mask the many explicit sexual references of the Zohar. Green summarises this succinctly when he highlights the Kabbalists’ core tenet “that arousal causes blessing to flow throughout the world. This is the essential story of Kabbalah, and the Zohar finds it in verse after verse, portion after portion, of the Torah text.” (p. 65)

“Undressing the textual bride,” as Green puts it, was a characteristically erotic experience both in process and content (p. 66/70). The act of “stirring the female waters” can thus be read as the mystery of the tzaddiq being able to activate the impulse of the sefirah Binah – just as much as an allusion to the actual skilful sexual act of arousing the female partner to release her sexual secretions.

His task was to direct the aroused power of his kauvanah, or spiritual intention, toward Shekhinah, thus stirring the female waters within her so that she aroused, the tsaddiq above to unite with her, filling her with the flow of energy from beyond in the form of his male waters, the lights from above as divine semen. As she is filled, the fluid within her overflows to the lower world as well, and the earthly tsaddiq receives that blessing. Here the paradigm is of a fully coital expression of sexual union, seemingly closer in some ways to the religion of South India than to the virginal and celibate piety of Christian monks. (p. 96)

Such fantasies of literally rescuing the universe through an act of male potency might seem equally juvenile as dysfunctional to the modern readers. Yet, they open a vista to appreciate the canon of Zoharic texts in a much more chthonic and corporeal way than generations of Western practitioners have done since Christian Knorr von Rosenroth published his double volume Kabbala Denudata in 1687, or since S.L. MacGregor Mathers famously translated it into English in 1887.

At the end, at least for the 21st century recipient, it is precisely its strict separation of the “terror of sexual sin” (p. 115), as found in onanism, spilling of semen, etc. and the excessive sanctification of the marital sexual act which again reveal the Zohar as a man-made artefact, equally mystical in nature as intensely coloured by its own culture and time.

Conclusion

Green’s slender book does an astonishing and much needed job to allow these paradoxes to stand side by side without attempting to offer easy answers. He helps us understand the Zohar both as a “holy revelation and sacred scripture” as well as an essential component of “Jewish mystical lore” and a “sacred fantasy” (p. 3-5).

For the Zohar is all of this and more. It contains echoes and fragments of other ancient traditions, as well as signs of the time of its creation. It carries the tension of asserting the Torah as the source and hallmark of all wisdom and truth, and yet it aspires to lead its student into an open realm that fosters personal mystical encounter and divine revelation. The Zohar’s roots reach deep into the universal mystical soil, stretching across time and cultures, and anchor its student in “an intense awareness of divine presence and constant readiness to respond to that presence in both prayer and action.”(p. 5) And yet, the flowers the Zohar grew from the experience of such Divine presence are uniquely Jewish in kind — fascinating, stunning, and intoxicating in their creative imagination, striking imagery and profound meaning-making.

When we read the Zohar today as non-Jews, we enter a world that we can only ever begin to understand. Its publication in the 13th century was a break with the habitus of secrecy in conservative rabbinic circles. This stepping out and showing oneself to the world seemed necessary to counter aspects of the zeitgeist that appeared to the authors as a threat to their way of living. The Zohar, thus, must be understood both as a reverent expression of the Jewish mystical tradition and as a radical act of public resistance and opposition.

After more than twenty years of study of practical Kabbalah outside authentically Jewish circles, I commend Green's book as both the best written for beginners and a much-needed corrective for most advanced practitioners. May it appear on the bookshelves and curricula of all magical orders far ahead of the works of Adolphe Franck, Mathers, Crowley, or Papus. May it convey the paradoxical Janus view of all mystical experience better than most other books I have had the pleasure of reading on this subject: one face looks outward at the subjectively conditioned, transient phenomena of one’s culture and time. The other, the inner face, keeps its gaze directed toward the divine presence, which in its ecstatic reality and living eroticism, engulfs all that is physically manifest in a single breath.