‘Two Esoteric Tarots’ by Peter Mark Adams and Christophe Poncet

Review: Peter Mark Adams, Christophe Poncet, Two Esoteric Tarots, London: Scarlet Imprint, 2023, ISBN 978-1-9123316-75-5

by Mark Hewitt

Even though the two decks seem to be as artistically and iconographically divergent as it is possible to imagine, their occulted narratives strongly suggest that they rest upon a common spiritual culture. (PMA p.51)

There was a sense of synchronistic irony that on the same day I finished reading Two Esoteric Tarots, the art critic for the Guardian smugly announced that there is “no connection between the modern mysticism of tarot and its origins as an artistically beautiful game” (Jonathon Jones, “Dr Terror deals the Death card: how tarot was turned into an occult obsession”, 18/12/2023). I would certainly like to think that having read this new offering from Scarlet Imprint, an appreciation of tarot beyond the immediate superficiality of pop-culture might be awakened. This optimism is not unweighted; the publication of this book speaks in the shifts of dominants. The polysemous imagery occulted in these decks is now, thanks to both Adams and Poncet and their Tartarus-deep research, available for a wider audience to interrogate. This conjunction between Adams and Poncet provides a comparative utility between two strands of classically inspired, and deeply heterodox Renaissance thought. Here indeed be monsters.

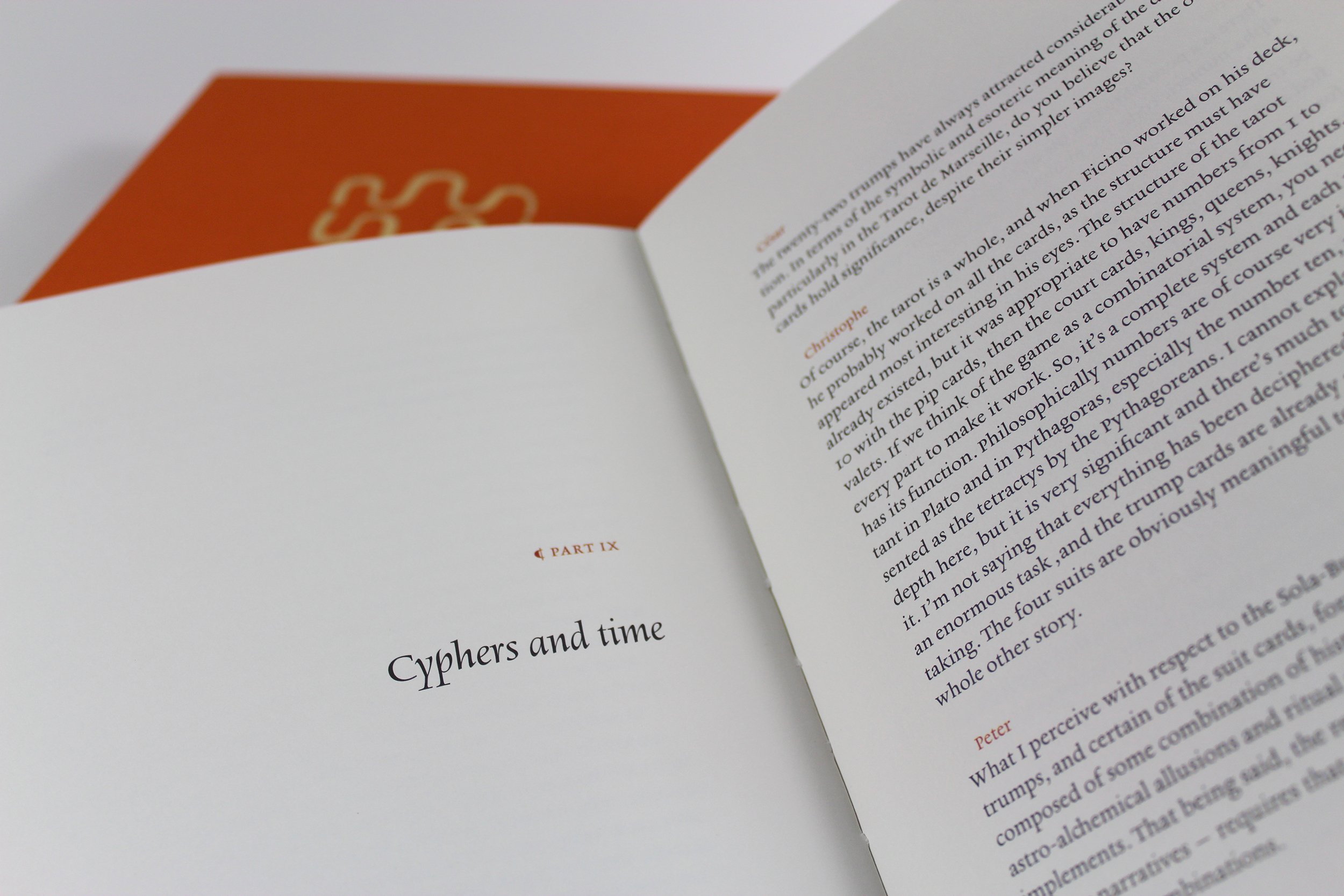

Two Esoteric Tarots is a dialogue between Peter Mark Adams and Christophe Poncet, mediated by César Pedreros who should be heartily thanked for aligning the pair. Readers will no doubt be familiar with Adams’ robust work in this particular field, with tremors caused by the publication of The Game of Saturn (2017) and its exploration of the Sola-Busca tarocchi still being reconciled. I was not personally familiar with Poncet’s work but considering the parallel journey he has taken with the Tarot de Marseille, he is an author, practitioner, and researcher I’ll be watching. There is a fluid, conversational tone to the book, which seems an obvious point to make given its structure; but considering the depth and richness of the subject the fact that it is indeed such a pleasing read is testament to the embodied knowledge both authors carry with them. It is a satisfying book that is easily navigated in a single sitting with good coffee and a pencil handy.

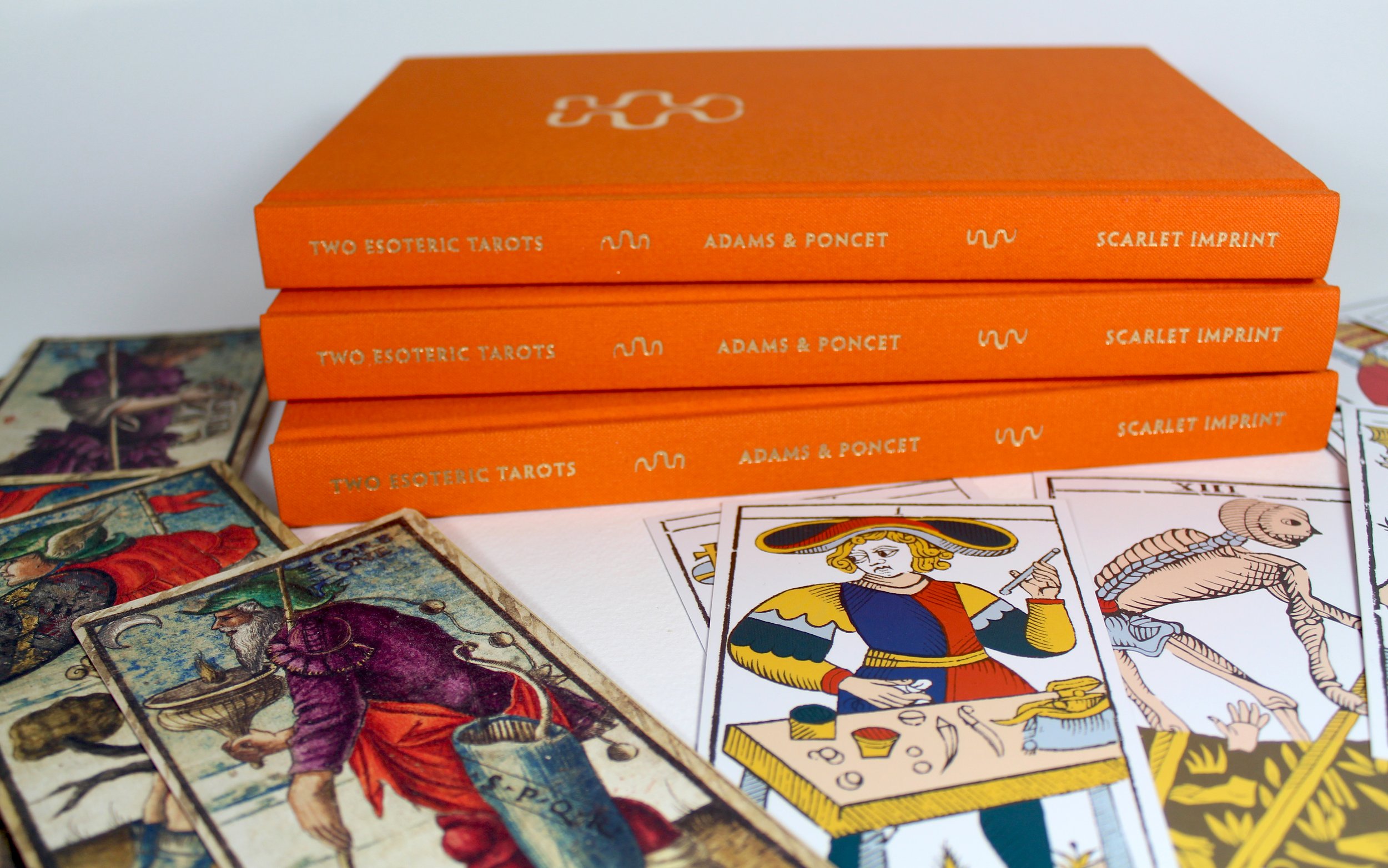

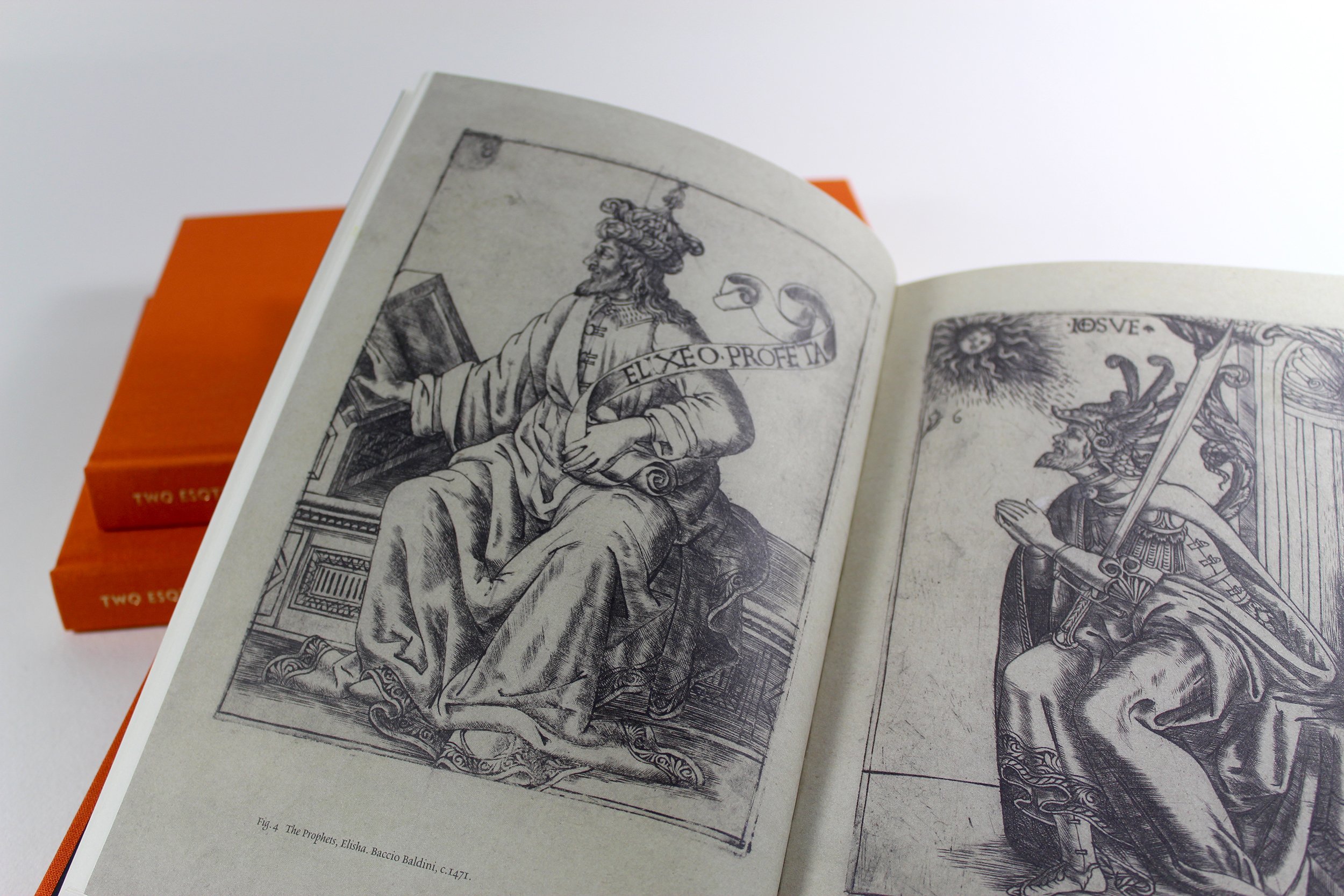

Over the course of twelve chapters, Adams and Poncet provide a wealth of evidence to illustrate their arguments, which in both cases reveals the transmission of Hellenistic mystery ritual into the imagery depicted on the cards. In the case of the Sola-Busca, this transmission was communicated via the influence of philosopher and scholar Gemistos Plethon. Plethon's own passion for exporting Greek and near-eastern literature out of Constantinople is arguably one of the most important catalysts of the Renaissance period. His Hellenist philosophy and particular brand of neoplatonic theurgy directly shaped the structure and content of the Sola-Busca. This tarocchi is no marriage gift or game as had previously been suggested, it is a tool to initiate contact with, and channel, a powerful Saturnian current; the ritual timing, processes and gestures hidden in plain sight. It is a work of distilled, instrumental Machiavellianism. This condensed version of the history of the deck is explained by Adams who manages to skilfully communicate the major points of what is an enormous subject. If readers are new to the Sola-Busca, then I envy what will be their initial rollercoaster read-through of The Game of Saturn!

This uncompromising realpolitik deck stands starkly juxtaposed to Poncet's own conclusions regarding the Tarot de Marseille. Poncet's research, birthed by frustrations generated by the blinkered materialist consensus of previous tarot histories, pushed him towards the same early renaissance period as Adams, discovering connections between the platonic and hermetic philosophical enquiries of Marsilio Ficino and the stylistic hallmarks of Sandro Botticelli amongst others in what would later become known as the Major Arcana. The Tarot de Marseille does not, as Poncet explains, utilise such specific, concentrated currents as the Sola-Busca. The specifics of its original intended usage are not clearly defined by Poncet, but considering his explanations concerning the involvement of Ficino, the Tarot de Marseille appears to function primarily as a guide to recognise the immortality of the soul and assist in its reconciliation with that of the Nous. Such deeply heretical philosophies would require multi-levelled encoding and the then-novel format of the cards provided both this and the delivery system by which to disseminate them; accordingly, Poncet’s scrutiny of the card imagery in relation to Ficino’s thoughts is persuasively shared. His observations on the process of metempsychosis in comparison to certain cards is a particular treat.

This distinct difference between the tarots is explained by an exploration of the personalities behind the design of each, Pellegrino Prisciani and Marsilio Ficino respectively. This diametrically opposed approach is satisfyingly explained in simple terms as one being “of raw power of ruthless domination of violence” and the other of “a luminous tarot, a sunny tarot, a tarot of universal love.” (p. 67) Despite the Tarot de Marseille predating the Sola-Busca by a decade, Poncet poetically imagines a dialogue between the creators, “there is a secret conversation between the two decks and, behind the cards, between their authors. It is as if the two designers were competing in some sort of contest of erudition and cleverness to create the most subtle of mind games.” (p. 86) It is in this playful spirit that the research for Poncet’s work has been conducted, stating: “As soon as I started investigating the Tarot de Marseille, I felt like I was mysteriously helped every now and then, as if some providential hand was giving me the clues to continue my progress.” (p. 106) These “signs following” (p. 20) as Adams describes them are indicative of this kind of work; the spirits behind the cards are in need of relation and it is genuinely wonderful to get a sense of this collaborative working.

Whilst both decks were initially designed to be accessed by only a select elite, it was the Tarot de Marseille that became the most ubiquitous deck of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. How this process occurred is not elaborated upon by Poncet. This would have been my only criticism of the work, but it must be noted that this publication is an amuse-bouche to a future Tarot of Marsilio series by Poncet which will also be published by Scarlet Imprint, so I am sure that I will not be alone in looking forward to his elucidation on this and a host of other exciting avenues of thought and practical advice.

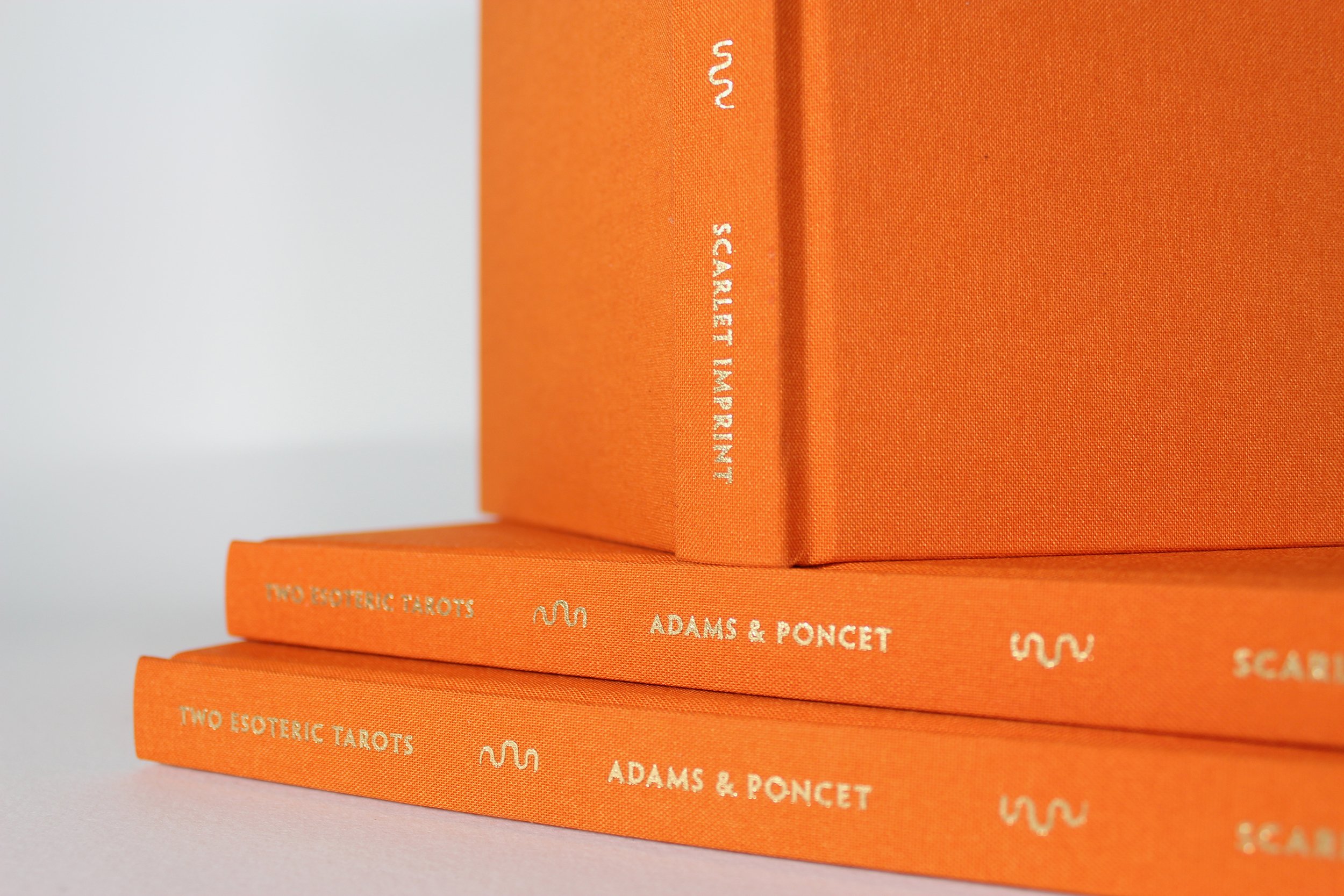

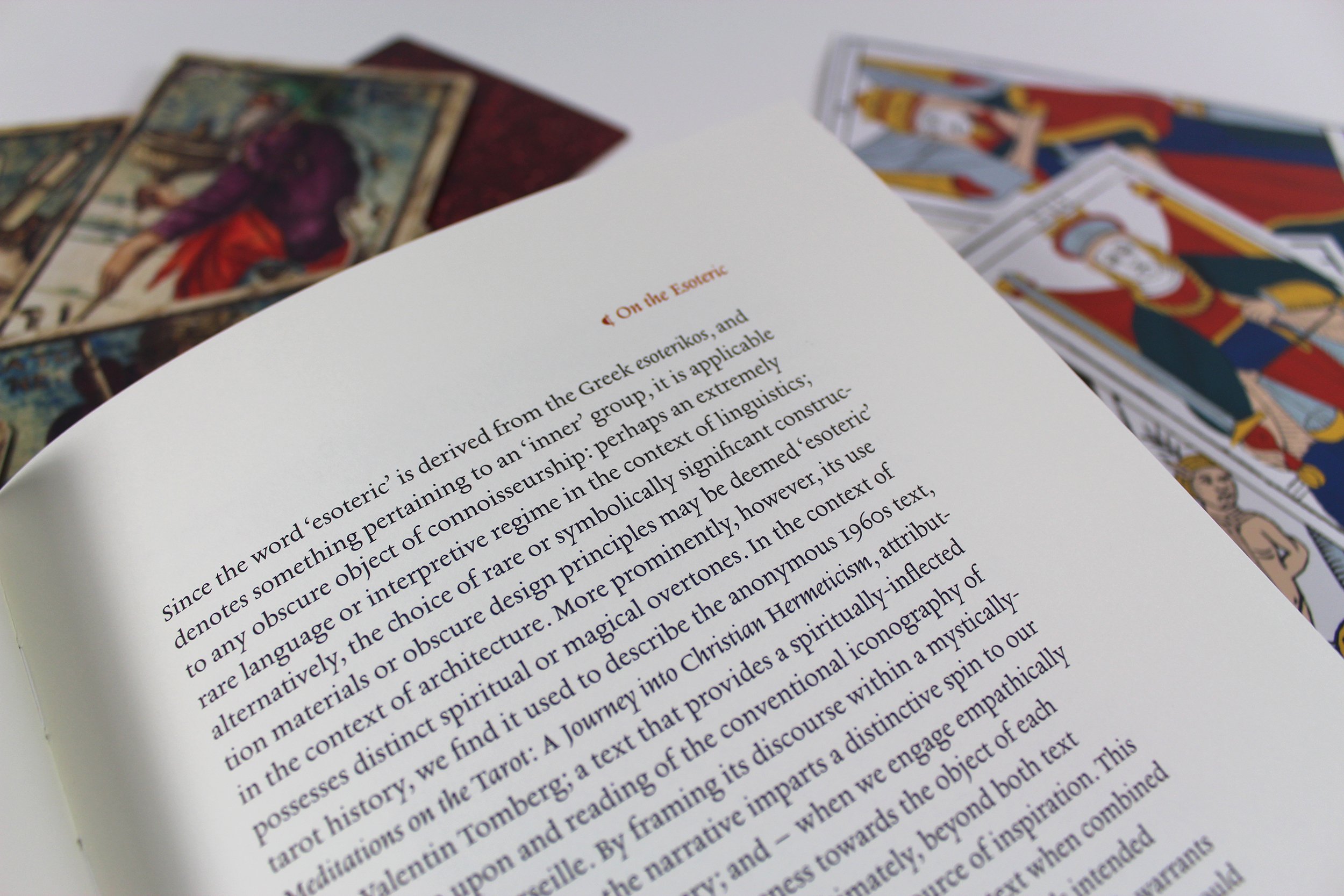

As with all Scarlet Imprint titles, the physical book and paper stock is of the usual high quality and a tactile delight. Likewise, the formatting, typeface, and printed colour images are a joy to behold. I was particularly charmed by the cover iconography and its transmutation on the final page; a beautiful visual shorthand for the meeting of serpens sciendi and coming into an affinity with each other. Both formats are affordable and the magical community as a whole owes a great deal of gratitude to publishers like Scarlet who accommodate for all pockets whilst still valuing the book as a repository of knowledge and a talismanic object.

I would recommend this publication to anyone with an interest in the tarot, and it works well as both an introduction to the historical, cultural, and spiritual contexts of both the Sola-Busca and Tarot de Marseille. It is a triumph of two passionate and sincere researchers and a genuine benefit to an audience within and without the magical community – perhaps even art critics.