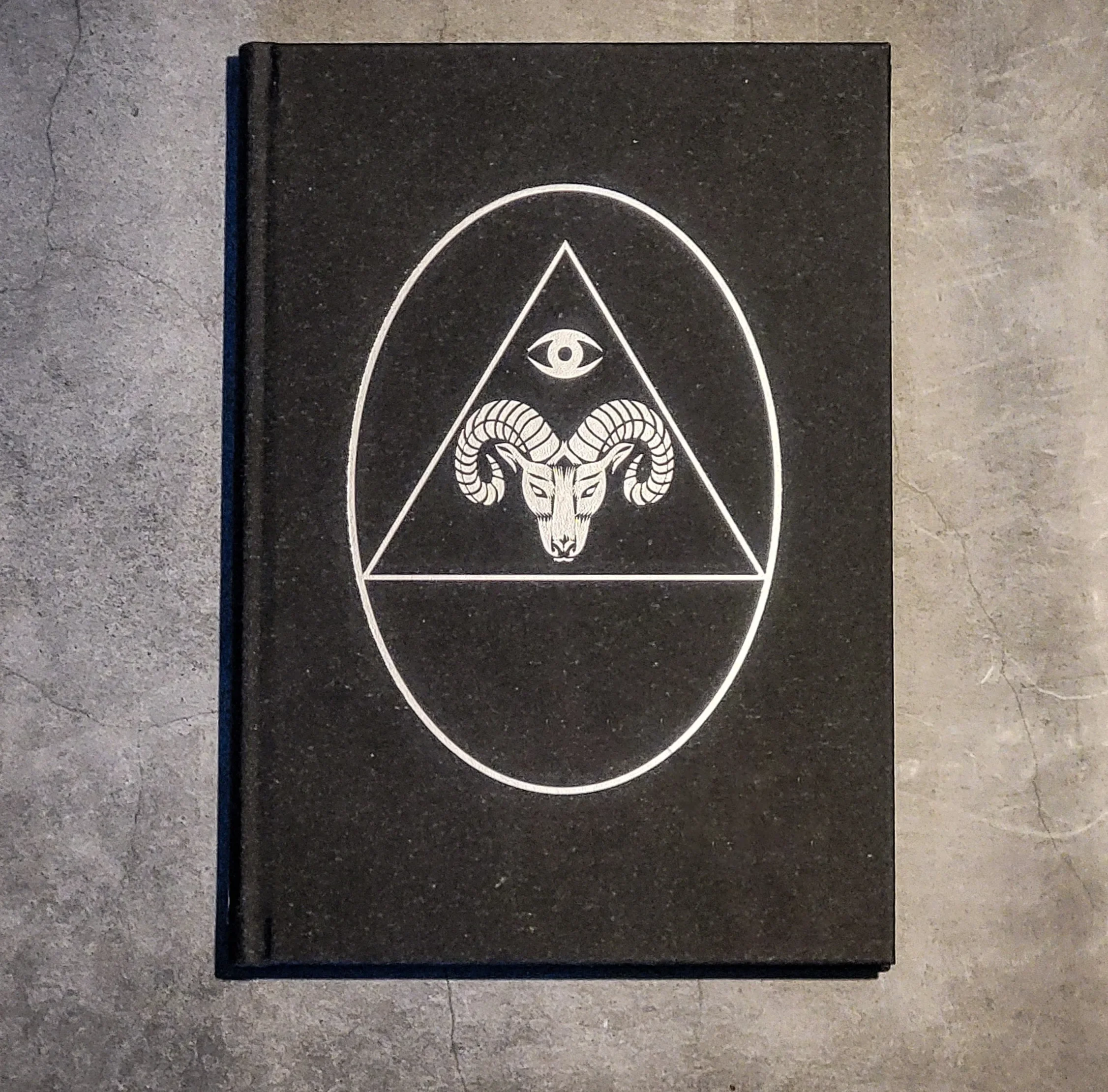

‘The Faceless God’ by Thomas Vincente

Tomas Vincente, The Faceless God (Second Edition), Munich, Theion Publishing, 2025

Review by Craig “VI” Slee

The Faceless God by Dr. Tomas Vincente is now in its second edition, out from Theion Publishing. That there even is a second edition is testament to something. Yet whether that something is something in particular – or something more ambiguous, amorphous and general – only the readers will be able to tell for themselves.

This is something that Vincente writes of soberly as a bona fide (albeit pseudonymous) academic scholar of religion. Yet beneath the engaging and clear prose lurks something ecstatic. Something that seems to exist as a phenomenological experience, arising out of the fertile black soil of the dreaming mind.

I speak, of course, of the eponymous deity-figure-concept-phenomenon, which Vincente ably and evocatively describes. This Faceless God is a presence which is not limited to the personal idios kosmos of Howard Philips Lovecraft, so Vincente suggests. Instead, Lovecraft’s fevered dreaming (and apparent subsequent experience of symptomatic illness) which gave rise to his ‘creation’ of the figure known as Nyarlathotep, is revealed as a potentially transpersonal phenomenon. Its emergence via the mind of a fearful writer of 20th century Weird Fiction may simply be its most recent cultural manifestation.

But, Vincente writes, Nyarlathotep is but one instantiation of something far older, weirder, and all-suffusing than the phantasies of a man from Providence, Rhode Island.

The key here is that the idiom of the Faceless God is precisely that: something which is not bound by literalism. That is, it is not enough to refer to the figure as mere metaphor but, as Vincente discusses, it appears to be a phenomenological experiential reality which the author traces throughout such manifestations as ram-headed Egyptian deity, Sabbatic Devil, Black Pharaoh, or Osirian cult as manifestation of the Hidden Sun.

This book posits that key elements of European witch lore, particularly those involving the Sabbatic Goat and its hierophant – the Black Man of the Sabbath – are profoundly resonant with the archaic cults of Osiris and his emissary, Anubis. (p. 21)

Notice the words “profoundly resonant”.

To say that Osiris is Anubis is the Sabbatic Devil is Nyarlathotep is Goat of Mendes, or any of the things, concepts or beings mentioned in the book’s five chapters, is – pun intended – to miss the point of this work, which is in fact multiplicitous and fanged enough to puncture boundary and category.

This book seeks to reify the dream-cult of Nyarlathotep. (p. 37)

On the surface, this seems like an outlandish claim – and that is, quite precisely, what it is. A claim of, and with, the outlandish.

claim(v.): c. 1300, “to call, call out; to ask or demand by virtue of right or authority,” from accented stem of Old French clamer “to call, name, describe; claim; complain; declare,” from Latin clamare “to cry out, shout, proclaim,” from PIE root*kele- (2) “to shout.” Related: Claimed; claiming (source: Online Etymology Dictionary)

This call of the “outland” is the call of the unknown stranger, the messenger bringing the unfamiliar which disrupts what we know, with distinct category and delineation breaking down, and in doing so, re-ordering the way we relate to, and with, the world.

This cry, set to print by Vincente, is quite clear in all its paradoxical obscurity. The multiplicity of forms which the author details are not supposed to be iterations of the same “thing”. Rather, there is no distinct unitary “thing”; the book is not a case of excavation to find the “true face”, or “the real truth behind” anything. It is not an attempt to habilitate Lovecraft as an unwitting occultist, or an unconscious channel for some sort of Outside-entity.

Rather, in a sense, it is a phenomenological cultural survey. By this I mean it is a consideration, and contemplation of the way certain phenomena or phenomenon might be traced throughout history. Much like another Theion offering, The Cult of The Black Cube, with its emphasis on the Saturnine Deity, so The Faceless God shows us things, and invites us to make connections through the author’s prose. In this, Vincente shows no shame in explicitly telling us that this is an “inspired and inspirited book” (p. 18). Neither, in his occasional gematria excursion, does Vincente shy away from the comprehension that it is an exercise in magical pattern recognition. While acknowledging the work of Kenneth Grant in this mode, the gentle differentiation (and critique) between Vincente’s use and that of Grant is well taken.

Where Grant tended (particularly in later works) to use gematria as material building blocks for his Nightside narratives, Vincente confines the gematria to a few specific usages, almost as a moment for the magician to emerge, sideways as always, from the robes of the good academic doctor.

Yet as well as a survey, the book also presents readers with several rituals and practices which purport to enable a practitioner to encounter the actualities of The Faceless God.

So, what is it, in this reviewer’s opinion, that sets the Faceless God apart from other kinds of so-called “darque fluff”, as Jake Stratton-Kent memorably coined the term?

One, as in the first edition, Vincente is not writing to be edgy, gother-than-thou, or merely in love with the Lovecraftian aesthetic. Rather, this is a specific exegesis of a particular understanding and awareness which the author’s scholarly background and training allows.

Secondly, it becomes quite clear that there is an underlying worldview, or ontology, within which Vincente is operating. This is not throwing a series disconnected-but-aesthetically interrelated concepts at a wall and seeing if they stick.

Rather, as already alluded to, it is the “facelessness” which comes to the fore, the challenge to notions of identity-as-necessary-substrate for agency and existence itself. The notion of Nyarlathotep as soul and messenger, per Lovecraft, is key. The Faceless God is not some dark angel with bat wings, but is, instead an ἄγγελος (angelos). A herald, a crier out; the one who is plenipotentiary, not just representative or agential. Rather, the distance is collapsed between messenger and that which sent it forth; the medium becomes the message. But they are never the “same”.

This is rather hard for many to understand. Clearly, there is a difference between Nyarlathotep and Azathoth – which Vincente suggests may have been named unconsciously in reference to the quintessential alchemical Azoth, seething and bubbling.

There were, in such voyages, incalculable local dangers; as well as that shocking final peril which gibbers unmentionably outside the ordered universe, where no dreams reach; that last amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the centre of all infinity – the boundless daemon-sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin, monotonous whine of accursed flutes; to which detestable pounding and piping dance slowly, awkwardly, and absurdly the gigantic ultimate gods, the blind, voiceless, tenebrous, mindless Other Gods whose soul and messenger is the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep. (The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, in: H.P. Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness: and Other Tales of Terror, edited by August Derleth, London: Panther Books, 1968, p. 156-157)

Yet that idios of Azathoth is, per Lovecraft, the entire kosmos. Literary scholars such as S.T. Joshi, whom Vincente’s footnotes regularly invoke, have spent time discussing this in papers, essays and books, so we shall leave the literary angle here, and muse more upon the magical.

In the work of Lovecraft, Nyarlathotep is known by many forms and there are many different cults worshipping each of these forms, sometimes unknowing of their shared reality. One of the most popular and enduring Table-Top-Role-Playing-Game supplements based around Lovecraft’s work makes this clear in its title — Masks of Nyarlathotep. First published in 1984, and continually in print since, it takes players across the globe to deal with manifestations of the dark god. Yet what we are interested in here is not roleplaying, but rather the phantastical and world-spanning nature of this imagery in terms of the dream-cult Vincente seeks to reify.

I am deliberately using the spelling of phantasy and phantastical in this review to differentiate the imagistic, magical experience which is in distinction to traditional ideas of fantasy. In this, I am making reference to φάντασμα – phantasma – those which are variously translated as “ghost”, “apparition”, “vision” or, “phenomena” “dream”. As I wrote in my other Paralibrum review of Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination:

[T]he phantasma, the appearances, are in actuality, capable of being revealed as unconditioned imaginal apparitions. Apparitions which contain and are potencies which enable us to heal the body and soul. The defamiliarization process is not one which is anthropocentric – it requires re-cognition of the gods, presences, and powers with the eyes of the heart. It needs the more-than-human.

In that review, I also quote Hanegraaf’s point:

“Noetic perception” as understood by the Hermetica […] are not the normal “intellectual” or ”mental” activities but are claimed precisely to go beyond them. They have absolutely nothing to do with thinking, let alone sensory perception.” (Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination, p. 15)

This, then, is how I suggest Vincente (an academic scholar in an area close to Hanegraaf’s field of Western Esotericism) may stand out from the “darque fluff” – at least to the discerning reader. This is not to say the book is without flaws: as a reader I should have liked each chapter to be even more in-depth, but I comprehend that such a survey cannot do that and still keep its overview structure, even with the extended material of a second edition.

Nevertheless, one could conceivably treat each chapter as a “Mask of Nylarathotep” – a not-face of the Faceless God, which is not an identity but a territory, an environment, to explore.

If we suppose, within the realm of the Lovecraftian lens, that Azathoth is the dreaming idios kosmos; that it is a defamiliarisation of the Azoth as universal remedy and solvent; might we then suggest that all phenomena are phantastical? That is, phantasmata are, per Hanegraaf:

[An] unruly stream of mental imagery charged with emotion that fills much of our conscious and unconscious life on a daily basis. (Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination, p. 2)

Note that image does not limit itself to pictorialism; those with aphantasia – the inability to visualise mental images – still possess mental and sensory contours and impressions. That is, it is merely the visual which is not easily considered. The stream of phenomena which make up the play of existence exceed our conventional notions of dreaming or imagination.

In a spectacular inversion of the expected, the daemon sultan Azathoth that is, and gives rise to all, has no koinos kosmos, no universality or commonality in the sense of sameness. It is not the “transcendental monad” David Beth speaks of in his Children of The Abyss essay which serves as The Faceless God’s afterword.

The apparent incomprehensibility of Azathoth, the “irrational” and “idiotic” nature of reality terrified Lovecraft. Even his racisms, misogynies and fears of miscegenation, his stories of amorphous tentacular forms, could be conceived as terror of the collapse of category, outline and distance — singular, monadic, and pure distinction collapsing in the endless cosmogonic stream of unruly sense impressions from which there was no escape.

So where is the koinos kosmos? If all that is, is the idios of Azazoth, what then? This is where the Faceless God comes in, as angelos, as “soul and messenger”, like the nous spoken of in the earlier review:

The nous then, is not the intellect, nor is it the-thing-that thinks. It is the principle which re-cognises the world as it truly is and reveals itself-as-within-and-integral-to-the world, yet also beyond the boundaries of the same.

Ontologically, it is an ultimate reality, while epistemologically it is the capacity to access or comprehend that very same reality. (Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination, p. 163)

It is this aspect which renders Nylarathotep as “The Crawling Chaos”, as a “Hermetic” figure which departs from apparently traditional senses of the same. One might perceive this as an “Alogos”, that is against the logocentric tendency to name and categorise. Yet, as discussed above, this noetic reality is koinos kosmos. I argue that the horror Lovecraft expresses as “The Crawling Chaos” is, paradoxically, the logos which shatters logocentrism — precisely because it infects everything. There is nothing which is not contaminated by, with, and through it.

In this sense, Lovecraft’s horror of corruption by the same is the horror that altered states of consciousness bring altered states of knowledge, of total immanence. The paranoid style that, beneath the surface, reality is fundamentally beyond our ken; that we are as motes in a vast oceanic night, at the mercy of incomprehensible forces beyond conception.

What The Faceless God suggests to this reviewer is that far from merely being a tale of a vile aberration, or thrilling tale of terror, or the sick-dream of a socially isolated and repressed writer, the creation of Nylarathotep was a shocking experience of relating with, and-to altered states of knowledge and knowing. Lovecraft’s obsession with “things that men were not meant to know” could be, in fact, a reactionary response to an unconscious encounter with nous.

In taking us through the chapters, to remind the reader, Vincente seeks to point to those “archaic cults of Osiris and his emissary, Anubis.” In an echo of Hanegraaf, this could be read as the heartland of Nyarlathotep — a black pharaonic character emerging to alter the world we know irrevocably. While we must be careful to guard against orientalism and exoticism, it is nonetheless a fact of historical scholarship that Ancient Egypt and its religious and spiritual milieus existed for an extraordinarily long time and cross-pollinated with and influenced many others throughout the Mediterranean and, indeed, possibly further afield.

It is perhaps no surprise then, that the dream of a “magical Egypt” resurfaces as a threat to rationalist western modernity in the mind of Lovecraft, with all the revelatory apocalypticism that this may imply. That much of Enlightenment thought is thoroughly indebted to preservation of and iteration upon Egyptian, Greek, Indian, and Roman ideas by Arabic scholars is currently not popularly well known. Such realisations fundamentally challenge the constructions of “Western”, Global North, Global South etc. as fixed categories. The motif of the “half-crazed Arab” Abdul Alhazred, despite its ableist and racist connotations may in fact be far closer to a broader reality than Lovecraft knew when it came to esoterica.

As such then, it is precisely from this diffusionist sea of concepts and experiences, filtered through hearsay, confabulation, and genuine esoteric reality and praxis, that dreams of witches in Europe emerged. That this amorphous ocean of knowings existed in spite of rejection by a so-called “rational” worldview is the very definition of esotericism.

The Faceless God as a text contains two pieces by David Beth. Some may find the first somewhat highfalutin or purple in prose. Yet after reading the second, one might come to realise that the unusual style serves an evocative purpose, focused on evocation of certain kinds of experience. Suddenly, something which seems potentially over-wrought is actually found to be dense with meaning and context.

Similarly, then, there are those (myself amongst them) who think there are better, more complex writers of Weird Fiction than Lovecraft. Yet it remains undeniable that for all his references to unknowability, strangeness, and a tendency towards habitual vagueness, his evocations succeed in spite of themselves. It is all too easy, today, in a world which is known and surveyed to an almost unfathomable degree, to mock the very concept of incomprehensibility as a fundamental undoing – or coming-undone. It is also far too easy to treat the esoteric as purely an ancient outrider of context collapse, a harbinger of our so-called post-truth order, as sloppy thinking or suchlike.

As The Faceless God gestures towards, there are presences that crawl chaotically through time and space – beyond the ordinary co-ordinates of space and time, and our regularly habituated geometries. That these presences may defy language, grasp, time, location, and yet still exist – and in that existing generate altered states with, and in us, which generate altered knowledges. And that they have done so for thousands of years.

This is the wordless cry, the noetic experience which renders us beyond sensibility. Only then, in hearing it beyond our ears, might we begin to consider the deep import of what The Faceless God seeds in the right reader.