‘One: The Grimoire of the Golden Toad’ by Andrew Chumbley

Andrew D. Chumbley, One: The Grimoire of the Golden Toad, Second Edition, Hercules: Xoanon, 2025

Review by Ian Chambers

For many long-time enthusiasts of traditional witchcraft, our first encounter with the East Anglian and Scottish Toad Bone Rite likely came through the work of folklorist George Ewart Evans. In Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay (1966), Evans recorded the oral traditions of the Toadmen — secretive horsemen and ploughmen said to gain occult power over horses through a forbidden rite. He later expanded on this in Horse Power and Magic (1978), detailing the ritual process of obtaining a particular bone from a sacrificed toad. According to East Anglian lore, those who succeeded were believed to wield power over horse and beast, having bargained with the Devil after retrieving the bone of a Natterjack toad that floated against the current of a river.

The Toad Bone Rite draws on ancient precedents from such luminaries as Pliny the Elder, Cornelius Agrippa, and Reginald Scot, and parallels similar practices found across Europe and Asia. In its most distinctively East Anglian form — sometimes called Waters of the Moon — the rite involves a symbolic crucifixion, excarnation, and the casting of the toad’s bones into a river to reveal the one imbued with power.

It is said in lore that there is an especial bone within a toad’s flesh that may be used as a talisman of great magical power. (p. 11)

Andrew Chumbley’s One: The Grimoire of the Golden Toad is both a gramarye of the rite itself and a reflection of the author’s personal experiences. First published in 2000, the late author’s work poetically and magically embodies a true sorcerous grimoire, maintaining a se nse of the mystical and occult throughout. Without elaborate exposition, the text assumes a level of research and magical experience on the part of the reader, evoking the spirit of the rite rather than relying on academic explication to unfold its inner meaning. Indeed, Chumbley’s more scholarly The Leaper Between (2012) fulfils more of that role, originating from his undergraduate dissertation material as an academic exploration of the Toad Bone Rite.

With Chumbley’s characteristic flamboyant, poetic, and inspired style — coupled with the pioneering and oft-imitated occult fine-publishing quality of Xoanon and its talismanic editions — the first publication made waves despite its limited print run of seventy-seven standard copies. This reviewer was personally recommended the book in the early 2000s as being among the only true witchcraft grimoires of modern times by an East Anglian witch. However, with limited copies available, and the rise of scalpers and armchair collectors driving prices upward, the book eluded many of us until this new release.

A deeply Gnostic work, One brings this arcana to the fore while seamlessly embedding it within an apparently rustic, agrarian character and mythos. The history and rite itself — including Chumbley’s now timeless addition to the body of lore — reflect a typically labouring-class mystery intimately tied to the land, agriculture, and its inherent spirit retinue. Evoking the presiding daemon of the work, Sabatraxas, Chumbley subtly hints at the Gnostic element without overtly pressing the point or diverting into exoticism, remaining instead grounded in rural English magic.

Inherited from Anglian horsemanship, this work does not require sophistication of language or study; yet neither should we assume that a working-class basis precludes a deep and heterogeneous culture. Too long has the “ignorant peasant” trope concealed the depth of the labourer’s philosophy — and Toadmanship is no exception. Indeed, Chumbley instinctively recognised the varied and ancient philosophy embedded within the lore of Toadmanship, nestled within rural occult magic. In One, he masterfully draws on these threads to reify the spirit of the work and its tutelary daemon, coalescing it into a workable and rich arcana.

Hidden within the apparent simplicity of the Waters of the Moon lies a lore that may be experienced as dense and rich, or else pure and direct — the “bare-bones” experience, one might say, yielding more discovery than endless study or scholarship. Given the nature of the work and Chumbley’s presentation of this grimoire as a working ritual text (as opposed to The Leaper Between), this is particularly pertinent. It is not necessary to recognise the Gnostic mythos within the rite or to observe its Christian syncretism — indeed, it may even prove an encumbrance if one intends to work the mystery and allow it to unfold its riches.

From even a cursory glance at the history of the toad bone and its intimate connection to the horsemen and the Society of the Horseman’s Word, one might wonder what this has to do with witchcraft. It is necessary to recall that the Toadmen Evans encountered were frequently regarded as practitioners of witchcraft — men who “had truck with the Devil” — and the powers they wielded were both respected and feared. In some traditional witchcraft circles, the horse can represent the compass itself — the eight-legged steed of Odin as arch-sorcerer. What we are dealing with here, then, is not modern witchcraft derived from Wicca, but a living example of historic rites long allied in folklore and the collective imagination with witchery and diabolism in Britain.

The work of the Toad Bone Rite is intricate and deeply personal, and this is vividly demonstrated in One. Stuart Inman of the 1734 tradition has observed that the ritual shares certain philosophical parallels with the Tibetan Chöd, cutting through the ego; and Chumbley, too, suggests that self-overcoming is an essential part of the practice of the Waters of the Moon. In identifying with the toad, the Toadman undergoes a rigorous and unconditional dissection of the self, ultimately being remade and challenged by the “Devil” for possession of the bone — or boon.

In Inner Experience (1943), the French philosopher Georges Bataille describes the self as a limited, bounded being, separated from the world by the constraints of language, reason, identity, and morality. The self exists in a state of discontinuity, defined by these boundaries that isolate it from others and from the sacred. Self-dissolution occurs when these limits are transgressed, allowing the individual to confront experiences that exceed the ordinary, rational, or moral order. Through such transgression — whether erotic, mystical, or extreme — the individual encounters a fleeting continuity with the world, with others, or with the sacred, momentarily dissolving separateness and accessing what Bataille calls “inner experience.”

In this self-dissolution, we may glimpse echoes of the slaying of Abel, which perhaps explains why the ploughman Cain is so closely alloyed to the rite, its lore, and its history, and serves as patron of the Horseman’s Word.

It should be emphasised that the Waters of the Moon is not to be undertaken lightly or without signs, omens, and careful consideration. Like much traditional witchery, it is not for everyone and can prove either a damp squib or a dangerous venture. As a solitary initiation, the rite is fraught with peril. Experienced occultists and witches understand that true initiations — if they “stick” — are life-altering experiences that transform, often rending the aspirant apart and disrupting their world and relationships as they are remade, not unlike the fate of the toad. If one is unprepared, insecure, or unbalanced in any of their “houses,” the psychological, magical, relational, or societal repercussions can be seismic and catastrophic. Given that coven initiations customarily provide a community or leadership to lean on in times of crisis — and initiations are, after all, a kind of managed crisis — there lies a responsibility upon initiators to watch over aspirants. In the case of the Waters of the Moon, the turning point must be faced alone; therefore, care and firm foundations are necessary. Many advise that omen should guide the way, and that one must not rush into the ritual. As the saying goes: “Don’t push the river.”

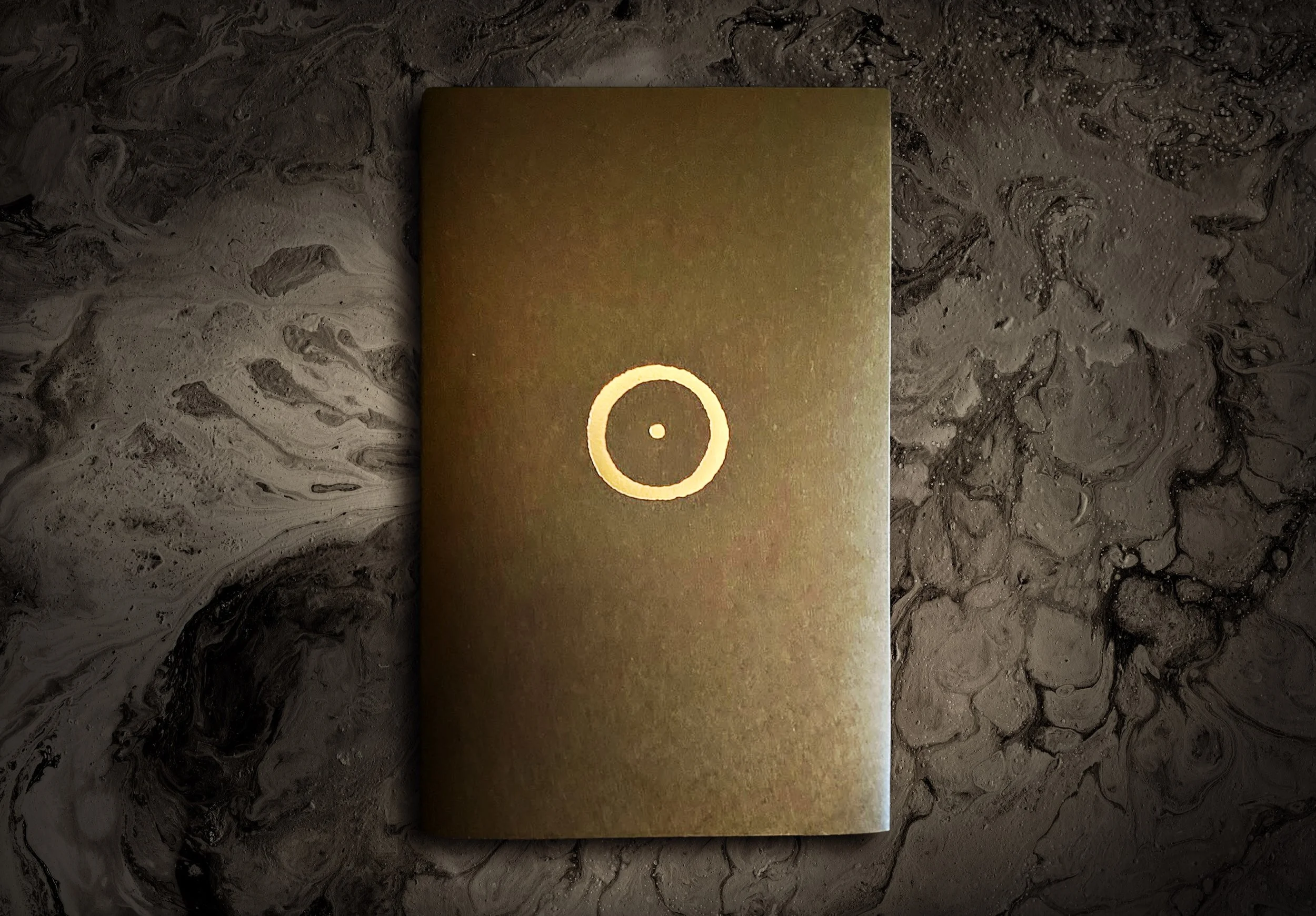

Originally published in just seventy-seven hand-bound copies, this new edition presents an updated blue cloth hardback with a striking black dust jacket, limited to an expanded 777 hand-numbered copies. As one would expect from Xoanon, the quality is beautifully understated, resonating with craftsmanship in both production and content — a book that veritably hums with magic. Chumbley’s work, as always, is not something one simply reads and sets aside; it is something to sit with, allowing its arcana to indwell you for a time, until you find yourself enamoured of its spell.

The book itself is divided into an Introduction, which elucidates the method of the Toad Bone Rite, followed by the Firstand Second Books, in which the mystery is elaborated in a poetic unveiling of the experience. The Consummation concludes Chumbley’s account, sealing the rite formally as the testament of the scribe. Frater A.H.I. and Soror S.I. — Magister and Magistra of the Cultus Sabbati — contribute a valuable afterword in the new edition, expanding upon the history and impetus of the book and Chumbley’s work.

Andrew Chumbley was a rare spark in the occult world generally, and the circle of witchcraft in particular. A student of comparative religion, scholar, practitioner, and mystic, his first published work, Azoëtia (1992), is a seminal text introducing ideas and specialised terminology that later crept into the popular witchcraft movement and are now often used out of context — such as “Crooked Path”. It is remarkable that Chumbley was only twenty-five years old when Azoëtia was published — a detailed ritual grimoire and study worthy of a lifetime’s examination into the ethos of the Magical Quintessence. Chumbley passed away on his thirty-seventh birthday, a mere four years after the first publication of One.

As both record and poetic inspiration, One: The Grimoire of the Golden Toad is a contemporary grimoire that presents the reader with a stimulating and influential book of magic — as distinct from a book about magic. At the same time, it stands as a testament to a historical and rural form of solitary initiation into witchcraft from bucolic East Anglia, tapping into the rustic horseman of old while reaching back through the ages. One should not be deceived by its brevity, nor treat the book as simple reading material. This is not a manual of ritual instructions to perform and boast about thereafter, but a text intended to ignite a flame — to inspire the wanderer to travel to midnight’s field, go to the river, to win or lose, and attain the power therein. A highly recommended work for the serious practitioner and student of historic witchcraft and magic.