‘Historiola: The Power of Narrative Charms’ by Carl Nordblom

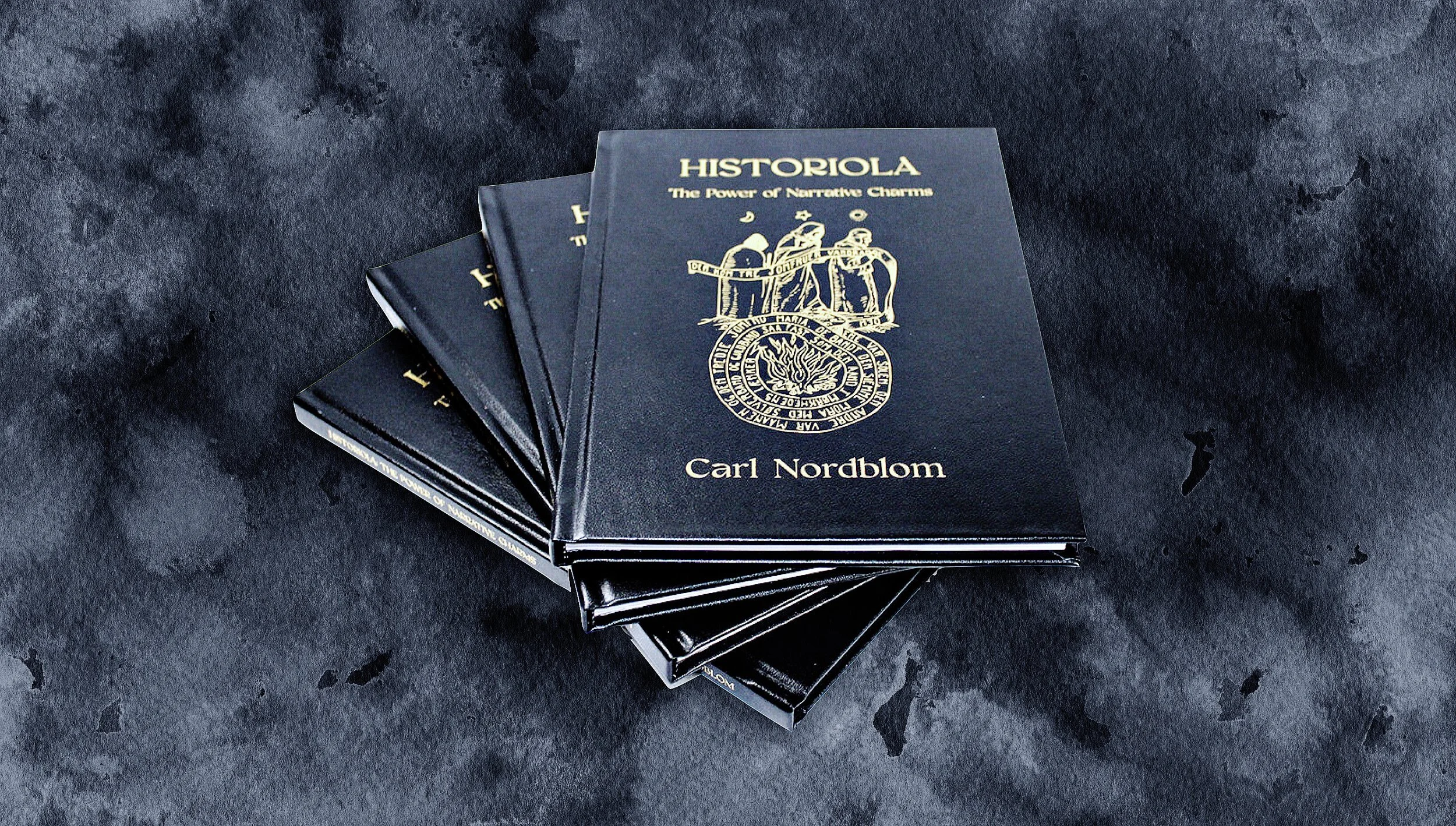

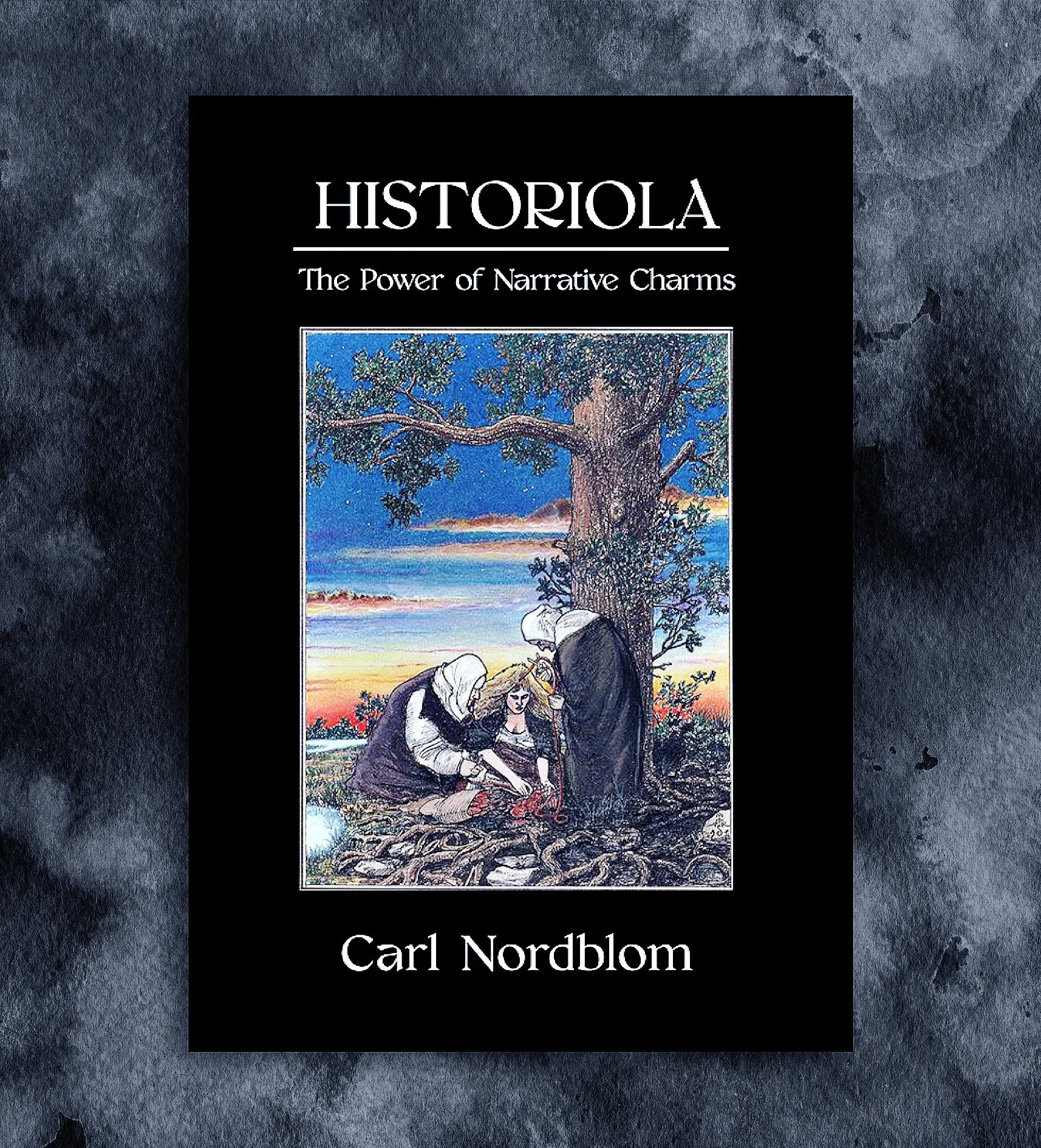

Review: Carl Nordblom, Historiola: The Power of Narrative Charms, West Yorkshire, England: Hadean Press, 2021, ISBN: 9781914166044

A slim black volume arrives, hard-backed and gold-lettered. It is carried by three Marys, three Norns, weaving their way along the roads. Soon, they are joined by Jesus, by Woden, by Artemis of Ephesos, by Brahma and the Garuda, and the Buddha, by a hungry wolf, and by the sulphur that rained down on Sodom and Gomorrah.

And these wanderers stretch out their hands and speak – flesh to flesh, bone to bone, blood to blood, knitting together body and soul, of animal, human and otherwise. They demand writhing, migrainous seas leave afflicted persons and enter the head of a bull, or be cast to the ends of the earth: to be destroyed utterly or elsewise banished to the wilderness or the bluest of mountains until Judgement Day. That sulphurous promise hisses from behind clenched teeth, raining down magic until either beloved, or enemy, or alien submits to the bindings of sorcerous fait accompli. Or should that be fate accompli?

At 89 pages, this hardback is attractively presented and laid out. While Hadean Press produces regular books in a variety of formats, they’re also known for their Guides to the Underworld series: A wonderful collection of what might be considered chapbooks, or pamphlets, by a variety of authors, for immensely reasonable prices. Why bring Hadean’s other work up in relation to this review?

For starters, because it is a book that you, the reader, may very well end up referring to repeatedly, as with the Guides. The hardback is, of course, rather lovely – but has benefits beyond the aesthetic. Having the volume possess extra solidity will no doubt be useful, for this little black book is as interesting and potent as the historiolae (“little stories”) contained within.

Nordblom situates his practice within Trolldom, his native folk-magical tradition emerging from the Norse countries, but notes that these narrative charms exist in many cultures. Hence his use of the academic reference point of historiolae – as a “term describing brief tales built into magic formulas, providing a mythic precedence for a magically effective treatment.” (p.16)

It is in the interest of this expansive view that this book is written – for while Nordblom makes clear his starting point, the text is concerned with a magician’s perspective on these narratives, rather than a mere repository of sources, or an academic’s recounting. There are a variety here, from the PGM to Swedish folklore to the Atharvaveda, the Merseburg Charms, 3rd Century Roman charms, and others besides. What this black book does, is to take these sources and investigate them to conceive of a methodology and practice behind them.

There are no rituals (save what are described in the charms themselves) and no gods or powers are summoned to visible appearance, or circles drawn. Instead, the narratives are treated as self-sufficient. That is, their efficacy is held to derive from the narrative itself. How is such a thing possible?

Nordblom argues that the words, images, narratives

[…] help us organize a specific situation so that we can approach it practically. [...] The magical images and words are [...] reliant on the web of meanings which we find ourselves in as partakers of various “worlds” and traditions, but also highly connected to a subjective level of experience via their actual application by practitioners in a lived real-world setting. (p. 11-12)

This is to say that the narratives emerge from a weaving-together of social, cultural, and religious context. They provide a method of narratively participating in the cultic milieu as Nordblom calls it. Lest we think of this as simple mimicry, or psychodrama, it should be noted that with these charms, the magician is making things happen by virtue of that which exists – they are “worlding” via the words and images. They are not borrowing power, or assuming a godform to become a power themselves – they are using what already exists, as a herbalist or other magician might use materia magica in their work.

So although the charm can be constructed using several different components, when established within a narrative context, the whole of the charm must be thought to function as a voces magicae, a formula proper and a narrative all in one. The narrative not only binds the other parts together, but can function on its own, it brings yet another ingredient to the charm. (p 22-23)

Such assertions put this reviewer in mind of a man famed for healing – the much-lauded medical doctor and hypnotist Milton Erickson, speaking about the concept which has become known as “utilisation”.

These methods rely on using the subject's own attitudes, sensations, thinking and behavior; Furthermore, aspects of the real situation [...] were used in a wide variety of ways. (Milton Erickson: Collected Writings by Milton H. Erickson: Volume 5).

He also speaks of “using the test person's own reaction patterns and abilities instead of trying to explain them to him.” (Milton Erickson: Collected Writings of Milton H. Erickson: Volume 4).

While the line between so-called hypnosis may appear blurry at times, it is important to note that this reviewer is highlighting this to complement Nordblom’s idea of a lack of otherworld. That is, magically, this is not about reaching some mythic otherworld and drawing beings into the lives of the client/and/or/magician. Rather, it is working to utilise the presences which are already part of the very fabric of those lives.

So, as we began this review by listing some of the presences in the book, we did so because they were already present, and indeed, became present through each other and the narrative. One only need to know one portion of those involved experientially, for the others to be drawn in also. Note the hungry wolf – this has no relevance to the Powers mentioned, no mythic narrative per se, but the reality of that hunger is already a pre-existent knowledge.

We know wolves are hungry, and we experience hunger ourselves. In this way the words and images of the narratives, while they may be conjured by the mind’s eye and speech, are acts of imagination, that is, acts of image-making.

This is not the same as making things up or wishful thinking – again we turn to the figure of the three weavers. What is created, fated, if you like, is a particular arrangement of that which exists in efficacious form. The image of the weavers on p. 27, combined with the quote “Three sisters were walking; one was turning, the second separating, the third dissolving” is emblematic of this. As Nordblom consistently notes, movement is often key to these narrative charms – both in terms of walking and other modes, but also movement from “starting conditions” to desired effect. The narrative is not static – rather, it is a world with its own movements and rhythms which is deployed to affect the circumstances of those involved.

This is why we may find, for example, Christian versions of certain charms where Jesus has taken over from Odin:

Again, however, we should not become blinded and believe that we have here something of a heathen practice “smuggled” into a Christian world. […] I would instead argue that it is the great utility of the charm as a healing method that must be the reason for it to be preserved. (p. 29)

This then, is not about the preservation of ancient rites; the living worlds of these narratives (which change, as they must, being enmeshed with other worlds, feeding-from-and-back-to them to be constantly rewoven) are potencies, meeting points, crossroads and confluxes of magical power – or so it seems to this reviewer. As Nordblom notes:

Of course the historiolae are […] never produced to entertain or explain anything - they are instead used in a context where they are perceived as having the ability to directly heal, harm and so on. (p. 38)

Nor is this perhaps the kind of Frazerian sympathetic magic which operates on the surface- level of likeness or resemblance. For all that the author does investigate this, as well as discussing the lens of Eliade, and other linguistic frameworks, he appears to be at pains to note that these narratives operate on an embedded gut level. They work, in essence, because they make sense – they are applications of how the universe works. That is, they are not partaking of some distant ritual time, some imagined past or future, but are in fact a kind of second sight in and of themselves – another look, another seeing; an image of a circumstance which replaces, overlays, and reweaves that circumstance and moves through it to a different direction or end goal.

At first glance, wording things as above may, this reviewer realises, makes it seem as if the historiolae are akin to the vision boards in various New Age practices, or perhaps something out of New Thought or Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. Yet, were that the case, surely the historiolae would focus solely on the end goal? There would be no need for the narrative of the figures involved to be powers or potencies.

It is here that the centre of the book lies:

The meaning of the story is, in this sense, that it is not a story at all, but rather that it is a direct and lived reality. [...] What matters in this case is not intellectual understanding so much as a direct and lived connection with the principles and beings mentioned in the charms, The ritualistic narrator has access to what many of us who live in a modern secularized society believe to be simply dreams or fantasy. (p.40-41)

That the stories are set in the past and brought to a completed conclusion is, perhaps paradoxically, Nordblom contends, what makes them more functional in the present. This is not to say that it is the power of some cosmic before-time that makes them functional, contra Eliade, but rather that they have happened already, and will happen again. This reviewer’s own magical experiments have always seemed more potent when presented as already happened.

Given the limitations of human perception, by the time we actually notice what is happening, something else is already happening – in this sense, we are lagging behind, and thus past-is-always-present. Thus, in a sense, the narrative of the historiolae repeat themselves regardless of whether the weavers are the Nornir or the Marys, whether the healer is Odin, or Jesus.

Magically speaking then, in terms of the narrative charms, Gæð a wyrd swa hio scel! ("Fate goes ever as she shall!”) as per the narrative of the poem Beowulf. It is the bringing of these into awareness which enacts their weaving – it is not copying these figures in these narratives which affects reality, but a participation-with them – a joining of words and images with the weavings of the weavers, as it were. To be clear, we are not talking about predestination – this reviewer is put in mind of rhythm, or perhaps a piece of music. The piece is known, it has a beginning and an end, but what is potent is the marriage between musician and piece.

There are always multiple potencies and parties involved. And perhaps this is why Nordblom states:

“I strongly advise a person wishing to pick up the practice of narrative charms to seek them out in their own native tradition and own native tongue. […] In other words, none of the English translations given in this book should be of practical use to you, and are only included as examples of structure and content.” (p. 61, n. 53)

In this reviewer's view, such an assertion is laudable compared to the glut of books containing rites to do and things to experience. What Nordblom has done is provide us with a framework to discover our own relationship to magical or sorcerous narrative within our own lives – a kind of praxis which enables us to think about word and image in a way which may be unusual to some moderns.

Yet in some senses, though we understand limiting oneself to words and images due to the source texts, we nonetheless find certain universalist assumptions of word and image as prime narrative conveyors somewhat narrow. Having said this, just as it is difficult to review 89 pages in such a way as to entice, and also inform the reader of general content, we understand extending things to modalities beyond word and image in 89 pages may not be possible.

This said, we might perhaps consider those who use other forms of language and storytelling and communication rather than word or image – be they deaf, blind, or somehow disabled, or part of a culture which conveys its rites and weavings through dance or bodily movement or other such methods. This reviewer is certain that other kinds of narrative (and general) sorcery may exist outside of what is considered usual by those of us in the so-called West, or normative embodiments.

Yet, this slim black book seems to serve as a more than adequate jumping off point for such explorations, and for that alone is recommended for those who may be interested in such things. So perhaps we should thank the author for providing us with only a glimpse of the many worlds of the historiolae which may present the enquiring mind with rich alterities.