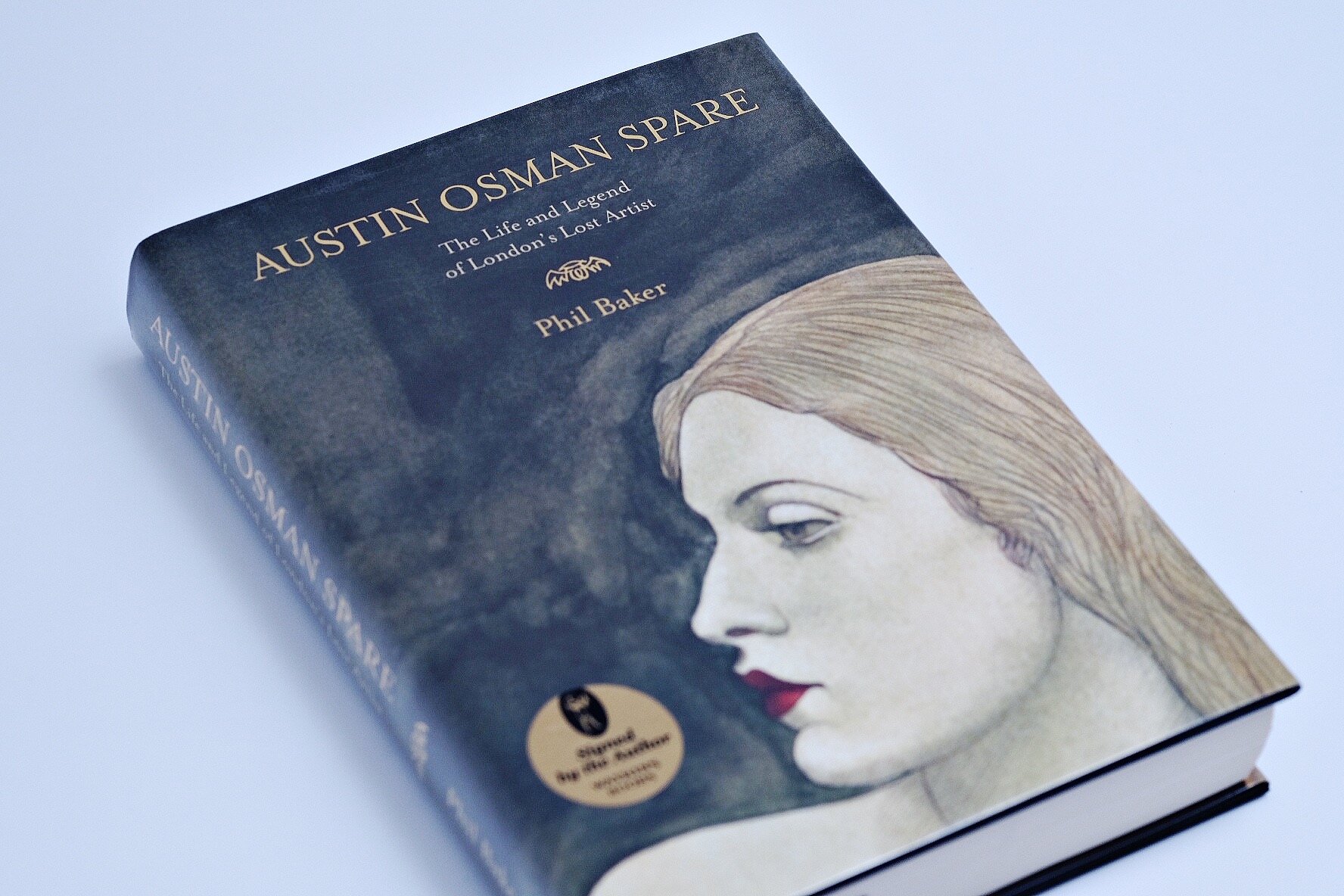

‘Austin Osman Spare’ by Phil Baker

Review: Phil Baker, Austin Osman Spare. The Life and Legend of London’s Lost Artist. Foreword by Alan Moore. London: Strange Attractor Press 2012, 2nd ed., pb., ISBN: 9781907222115

by Frater U∴D∴

A Strange and Gentle Genius: The Greatest Artist Britain Never Had

“What Phil Baker has accomplished here”, writes no one less than Alan Moore in his preface, “is little short of marvellous.” (p. x) So let it be stated right from the get-go: this effusive assessment is certainly no exaggeration. Nor is his preface one of those all too common vacuous courtesy pieces serving some undisclosed debt of mutual back-scratching between media workers. As a celebrated artist of no mean standing, with an entire magical system under his own belt, we can safely assume that Moore knows a thing or two about his artistic – and magical – forebear and colleague Austin Osman Spare and is in an excellent position to judge just about any biography of his. After all, much of this, to him, is familiar territory. Indeed he reveals that he had already been delving “for many years” (p. ix) into Austin Spare when he first learned about Baker’s project. In consequence his introductory words offer a lot more substantial information than a mere friendly go-along would allow us to expect:

In his relation to both art and occultism, Austin Osman Spare stands out as a strikingly individual and even unique figure […] While his line and sense of composition have at times drawn justifiable comparisons with Aubrey Beardsley and with Albrecht Dürer, if we seek a match with Spare the visionary or with Spare the man, surely the only candidate is his fellow impoverished South London angel-headed nut-job, William Blake. In both men’s lives we find the same wilful insistence on creating purely personal cosmologies or systems of belief, fluorescent mappings of the blazing inner territory that each of them clearly had access to. We find the same strangely iconic phantoms and grotesques; the same heroic readiness to embrace lives of poverty; the same tales of erotic drawings either burned or spirited away upon the artist’s death; the same sense of unearthly realms of consciousness both actually experienced and lucidly depicted. (p. vii)

There is, however, “one glaring difference” between the two, Moore goes on to expound: “while both men were equally ignored and marginalized during their respective lives” (p. vii), we have come to learn a lot more about William Blake since Alexander Gilchrist’s biography, whereas Spare “is a presence (or an absence) wreathed in mystery and often in deliberate mystification about whom even his greatest advocates have managed to dig up comparatively little.” (ibid.) It is this highly regrettable gap that Phil Baker essays to fill with exemplary meticulous thoroughness and sensibility.

But that’s not where the foreword ends. Without pre-empting the pointillist minutiae of Baker’s portrayal, Mr Moore offers up a more sweeping appraisal of Austin Spare’s own character traits as a prerequisite to AOS myth and legend building, taking into account that this confrere was himself very much given “to smudge the line dividing fact from fantasy” (p. viii), being, and forever remaining to his unrelenting core, “a man for whom material reality and the reality of the imagination were equivalent if not entirely interchangeable.” (ibid.)

To be fair, this biographical fuzziness isn’t all Spare’s own fault: there were a number of other contemporaries, industrious contributors that would merrily jazz up the legend, ranging from his original admirer and later bête noire Aleister Crowley to an “engagingly delirious Kenneth Grant” (ibid.) who operated for decades as an undisputed key player in the overall narrative of Spare’s life, both in his later years and in his posterity, but one who did bring quite a few problems of his own to the table. While Moore does point out some of the issues accompanying Grant’s idiosyncratic narrative, foremost his often lurid anecdotal style and his cranky prose, he does do him proper justice in the same stride by acknowledging the fact that, were it not for Grant, most of us would probably never have heard of AOS and his unique magical practice. He also takes pains to point out that

the startling and dream-like episodes […] attributed to Spare are our best way of apprehending what the world of magic feels like from within the sorcerer’s own mindset, and […] understanding the mythology surrounding Spare is vital to have a full, inclusive comprehension of the man; of who he was and what he meant. (ibid.)

These observations are anything but immaterial as they furnish the reader by way of some judicious guidance with an initiatory frameset before setting out on witnessing Phil Baker’s long romp through the intricately convoluted world of AOS.

Mr Moore goes on in his glowing survey of Baker‘s study, of which we will offer one final sample here:

Baker allows us access to Spare as, at least in part, a self-mythologizing fantasist without attempting to diminish the reality of Spare’s phenomenal accomplishments as a magician, artist or extraordinary human being. If anything, this emphasis upon Spare’s cat-shit and kitchen sink humanity serves only to make his glorious work of self-invention seem both more heroic and more genuinely magical. (p. ix)

Very well said – but what does it all mean? Glad you asked. So let's go find out.

Enter seventeen-year-old Austin Osman Spare, nonplussing his father Philip, a recently retired police officer, who can’t believe his eyes when he comes upon the newspaper headline announcing that a drawing of his son’s has just been hung at the Royal Academy, young Austin being hailed as the youngest exhibitor ever. (As Baker points out later in a footnote on p. 23, said well-meant claim was not quite precise: there had actually been two predecessors in 1897, both aged thirteen. Mere trivia? Perhaps, but it does seem to set an early precedent in terms of the persistent cloud of inaccurateness that was to haunt Spare’s entire life.)

This is May 1904: the commencement of a rising wave of publicity in the course of which the budding prodigy would be lauded by such venerables of the world of arts as Augustus John, George Frederick Watts, and John Singer Sargent. Here was the new Aubrey Beardsley, positively England’s finest draughtsman, with the press even speculating on his purported ambitions to attain to the eventual presidency of the august Royal Academy itself someday – a shooting star turned, de facto over night, into a veritable high brow household name. He would disclaim the presidency bid, though: “I no more aspire to be the President of the Royal Academy than I aspire to be a wastepaper basket.” (p. 25)

“Even allowing for a certain amount of hyperbole,” writes Baker, “a glittering career seemed to be on the cards. What could possibly go wrong?” (p. 1) What indeed?

After briefly recapitulating the history of the Smithfield area of London, somewhat infamous for its “unholy mixture of butchery and religion” (p. 5), where Austin was born on 30th December 1886 – “qualifying as an authentic Cockney” (ibid.) – Baker digs into his family and upbringing. He adds a lot of local colour to his narrative, mostly historic but some of it even quite current, covering architecture and lifestyle, commerce and folklore.

When he was seven, Austin and his family moved south of the river to Kennington, where he spent an overall happy life for a while. Again, Baker depicts the environment in graphic detail, investigates various events and determines possible early influences informing young Austin.

Foremost amongst these is the strong encouragement Austin experienced from both his parents once he became more serious about drawing, earning early accolades both at school and at home from his supportive family.

This aside, his relationship with his mother was quite strained from very early on. In consequence he transferred his filial affection to another, elderly woman whom he elected as his “second mother”: the now-famous “Witch Paterson”, known from various other accounts of his life. Spare, never the most reliable witness, it must be said due to his “life-long tendency to confabulation and self-mythologising” (p. 11), would allege that not only did Mrs Paterson seduce him at an early age, thereby changing the course of his life, she also introduced him to fortune-telling with cards, manifesting, as Baker puts it, “the power to materialise thought-forms to the point where another person could see them; not so very different, perhaps, from what an artist does.” (ibid.)

Alas, the veracity of this early tall tale leaves much to be desired: tangible evidence for instance. The popular lore, propagated by some accounts, of “Mrs Paterson” being the representative of some dignified ancient witch cult, is deconstructed; but while Baker essays to offer us a more plausible alternative, this itself is somewhat tenuous as well. Which is all a bit of a shame, seeing that it would have qualified as a superb psychoanalytical marker to explain Spare’s gerontophiliac obsession with hags, witches and ancient female demons in his later years. But as our artist would probably have been the first to acknowledge, life doesn’t always play nice, not even for biographers.

To render an impression of Baker’s graphic style and his ingenious knack of interweaving history, local colour and biography, let the following excerpt serve as a paradigm:

In his more daylight life, meanwhile, away from the doubly shadowy figure of Paterson, Spare was attending the very religious school of nearby St. Agnes Church. Originally a plain, shed-like building that had housed a vitriol works, St. Agnes had been remodelled by Gilbert Scott, the Gothic-revival architect. Larger than some cathedrals, with magnificent stained glass windows, it was a notably “High” Anglo-Catholic church; a place of ritual and incense, which caused violent controversy on its opening because the priest wore a white stole and Mary was hymned. From the Protestant perspective this was all too much, and more than halfway to “the drunken bliss of the strumpet kiss of the Jezebel of Rome.”

Nuns were a prominent feature of life around the church and school. The drawing of Spare’s which was hung on the wall of the classroom seems to have featured robed and cowled figures; this was the distant memory of a neighbour, and […] these figures were to become a lifelong motif in Spare’s work.

[…]

[Spare] also told a friend in later life that all he learned at St. Agnes was how to masturbate, but this was not true. It made more of an impression on him than that suggests, not least because he had been exposed to High ritual and religiosity, and given an intensified awareness of religion of the kind that often overlaps with occultism. (p. 13f.)

This goes to underline Moore’s dictum that

Phil Baker has established himself as among the very best contemporary biographers, especially as one who finds his subjects in the murkier and much less well-regarded tide-pools of twentieth century culture, where the fauna has a tendency to be both livelier and more unusual. (p. ix)

Before his 1904 picture hanging which set the publicity ball rolling on a massive scale, Spare had been apprenticed to a couple of firms specialised respectively on imprinting and poster designs, glassworks and stained glass manufacture. He had also been recommended for a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in South Kensington; drawings of his where displayed in the British Art section of the St. Louis Exposition as well as at the Paris International Exhibition; and he even won a National Mathematics Award in 1902 with a treatise on solid geometry. In 1903, he scored a silver medal when participating at the National Competition of Schools of Art, with the judges noting his “remarkable sense of colour and great vigour of conception” (p. 17): in short, it was honours upon honours.

Baker gives us a fairly extensive overview of what was going on in the world of art in this specific era, explaining who was who, including Spare’s personal contacts and his more remote influences. It was an eminently motley scene with plenty of talent and inspiration floating around, to which Spare obviously took with vigour and enthusiasm like the proverbial fish does to water.

Another fairly early influence proved to be Theosophy. Spare, throughout his life an avid reader, discovered Madame Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine, soon to be followed by Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy, the works of Eliphas Levi, and more. Sporting a certain flamboyance in his dress, he was not beyond some dandyism and to an extent adopted the roll of an enfant terrible at South Kensington art college. Many years later, one of his fellow students describes him in retrospect as “a fair creature resembling a Greek god, curly haired, proud, self-willed, practising the black arts and taking drugs.” (p. 21) Soon he would announce his plan to publish Earth: Inferno, his first book of drawings, soliciting advance orders. At college, he became quite close with the suffragette and political activist Sylvia Pankhurst, supporting her feminist cause and her campaign against the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (today’s Ethiopia), whereas she in turn proved helpful later in his life when his fame was in decline.

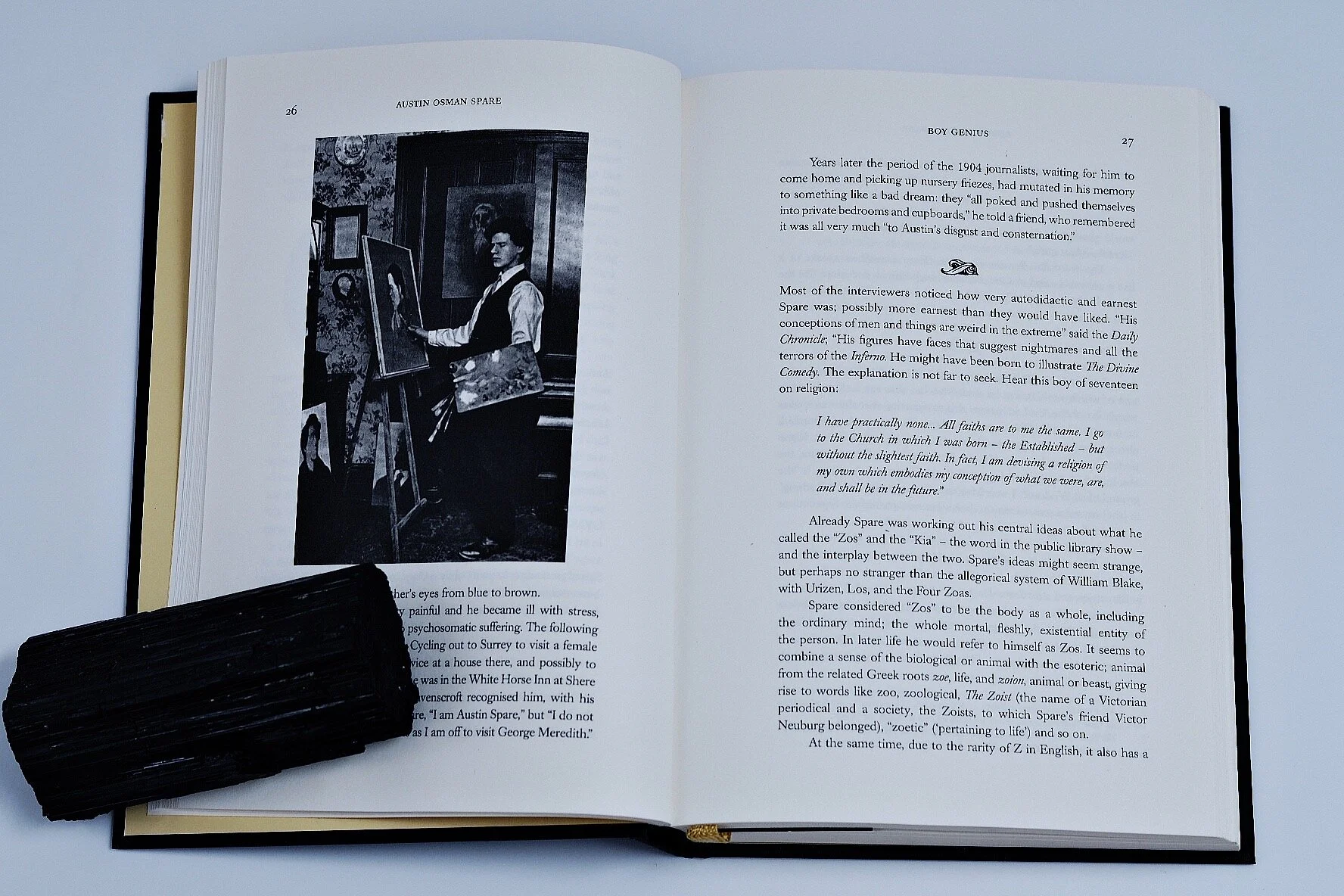

Being hounded by the Press waiting on the doorsteps of his home when he returned from college, with an endless stream of interviews to muster and having to keep track of the results, wasn't all roses, however, and private complaints soon ensued: “Spare found his celebrity painful and he became ill with stress, beginning a lifelong tendency to psychosomatic suffering.” (p. 26) While anything but a recluse at the time and not at all averse to praise and genuine admiration, he didn’t exactly embody the typical lounge lizard either: his natural shyness and introversion were at times excruciatingly painful for him to overcome.

He also focused on what was eventually to become his less public career as an occult thinker from early on.

Already Spare was working out his central ideas about what he called the “Zos” and the “Kia” […] and the interplay between the two. […]

Spare considered “Zos” to be the body as a whole, including the ordinary mind: the whole mortal, fleshly, existential entity of the person. In later life he would refer to himself as Zos. It seems to combine a sense of the biological or animal with the esoteric; animal from the related Greek roots zoe, life, and zoion, animal or beast, giving rise to words like zoo, zoological, The Zoist (the name of a Victorian periodical and a society, the Zoists, to which Spare’s friend Victor Neuburg belonged), “zoetic” (‘pertaining to life’) and so on. (p. 27)

Baker continues with several further, fairly speculative derivations of the term ranging from Zeus and Zanoni to unspecified “dental sibilant gods”, which shall not concern us here. Next, he addresses Kia.

The word Kia is more complex. Spare sometimes speaks of it like a universal mind or God, but it is less personal, and more like the Hindu Brahman or the Tao of Chinese philosophy. Spare associates it with a vulture, skulls and evolution, and it is at one and the same time the fertile void behind existence and also a soul-like state of supremely detached, self-sufficient consciousness. (p. 28)

Again, Baker goes on to discuss various Kia-associations encompassing Taoism, the Buddhist idea of the absolute void or sunnyata, as well as energy concepts such as ki, chi, and so on. But it seems there’s another, more overt source for Kia as well:

The most likely inspiration […] is Blavatsky and The Secret Doctrine, where the word Kia figures as a compound (Kia-yu) with an accent over the A like the one Spare tends to give it. Within a year or two he had finished a magical book or grimoire in decorated manuscript form, entitled ‘The Arcana of AOS and the consciousness of Kia-Ra’, which surfaced at Sotheby’s a few years ago. (ibid.)

Overall, his stint at the Royal Academy, where he never really learned anything of value in terms of his artistic craft, proved fairly frustrating for Spare, and he finally left without qualification in 1905 to pursue a living as a bookplate designer and illustrator. Around this time he also got involved on occasion with spiritualism, very much the craze of the day in all of the Western world, though he apparently viewed it with a high degree of ambivalence. Whilst beset by ever-recurring exposures of blatant fraud, pedestrian credulity, the most banal of revelations and general exploitative seediness, it did convey

something indeterminate and more precisely uncanny. It is this grey area of spiritualism, involving neither the spirits of the dead nor conscious fraud, that was the most thought-provoking for some witnesses, Spare among them. It seems to point to the uncanny weirdness of the human mind, and strange things happening within it. Spare left little direct record of his early involvement with spiritualism, but his work suggests that it marked him more deeply than anything else. (p. 40)

Thus Phil Baker, who also presents us with a detailed and enlightening analysis of Spare’s first work, Earth: Inferno, published in February 1905, and various possible influences informing it. He follows up by discussing some of Spare’s commissioned book illustrations and their respective context. While his biography is replete with photographs and original illustrations by Spare himself, not all of them equally familiar even to the Spare expert, Baker does spend a lot of writing effort on describing other artwork of Spare’s which is not featured by way of plates or illustrations in the book. This occasionally makes for some rather circumstantial reading.

Discussing the scant but existent references to Spare’s work in fiction, Baker finally arrives at his subject’s coming upon Aleister Crowley.

Crowley apparently told Spare that in their different ways, Crowley in his poetry and Spare in his drawing, they were both messengers of the Divine. It was the beginning of a professional and personal relationship between the two which was ultimately unhappy, and remains a puzzle. There is no question, though, that Crowley admired Spare’s work, commissioning illustrations for his journal The Equinox, taking artwork in exchange for a ceremonial robe that Spare couldn’t afford, and recommending Spare to Holbrook Jackson as an artist.

[…]

Crowley had joined a growing band of Spare’s patrons and champions, and already “a minor cult following that would last his entire life, to a greater or lesser degree” was getting under way. (p. 50)

There are plenty of other admirers, and Baker introduces us scrupulously to quite a number of them, in the same stride discussing Spare’s extensive work as a bookplate artist, interspersing his observations with references to art history and contemporary criticism, Austin’s stylistic penchant for “Nineties-style evil” (p. 51) and strangeness, comparing his own stylized “fancied brutishness” (p. 53) to Beardsley’s “stylizations towards the effete” (ibid.), and so forth. Here, Baker adroitly dons the robe of the art historian and connoisseur as well as that of the fastidious biographer. While possibly not of paramount interest to each and every reader in its obsession with detail, it does a fabulous job of making the general context of Spare’s environment come to comprehensible life.

What follows is a fairly extensive narrative centred on Spare’s sexuality and that of the varied company he kept. While many of his friends and sponsors were more or less openly gay or, as in the case of Aleister Crowley, vehemently bisexual, some of them (Crowley again included) finding the young prodigy erotically attractive, it remains unclear what stance Spare himself adopted in this respect. From the sources it appears that the protagonists involved weren’t at all decided on the matter either, speculating wildly whether he was actually a homosexual or not. For instance, one of his lifelong closest friends, Frank Letchford, claimed, citing another acquaintance, Sir Frank Brangwyn, that when Spare “dived into the tenements of Southwalk in the 1920s” (p. 57), it was in order to live his homosexuality in a less restrictive environment; whereas his friend Kenneth Grant believed that what made him do so was actually his desire “to have discreet sexual relations with old, elderly and even crone-like working class women there”. (ibid.) Spare himself, on the other hand, would claim that this was a period of erotic excess for him, saying that he had actually been living with a much older woman before he was sixteen, who eventually became pregnant but lost the child. He also told a friend that he had had an affair with a hermaphrodite at the time, with a Welsh maid of violent temper, and with a dwarf woman with a snub nose and a protuberant forehead etc. The authenticity of this erotic narrative is, of course, hard to verify for all the obvious reasons.

On the 10th of July 1909 Spare took the oath of a Probationer in Crowley’s Argenteum Astrum or Order of the Silver Star (A∴A∴), one of the enticements for joining possibly being that Crowley told him he wanted to recruit famous people in the arts. He eventually became friends with co-member Victor Neuburg and was introduced to others such as Ethel Archer and Nina Hamnett. Yet, he never actually became a full member, not even advancing to the lowly status of Neophyte, which Crowley, in 1912, would claim was due to his not being able to “understand organisation”. (p. 69) But “Spare,” writes Baker, “was a self-willed, anarchic character who not only couldn’t understand organisation but distrusted it on principle.” (p. 70) As for the more intrapersonal angle, Spare himself would remember Crowley only with a high degree of distaste after their final breakup.

He also became a staunch believer in the power of the unconscious which had been a topic of public discussion since around 1886 under the then more fashionable term “subconscious”. Baker analyses the evolution of this debate in some detail, covering researchers such as William James, Frederik Meyers, Pierre Janet, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and others. But whereas Freud was loath to condone “the black tide of mud of occultism” (p. 74), this was precisely what Spare would vigorously embrace, writing: “MAGICAL obsession is that state when the mind is illuminated by sub-conscious activity evoked voluntarily […] for inspiration. It is the condition of Genius.” (ibid.)

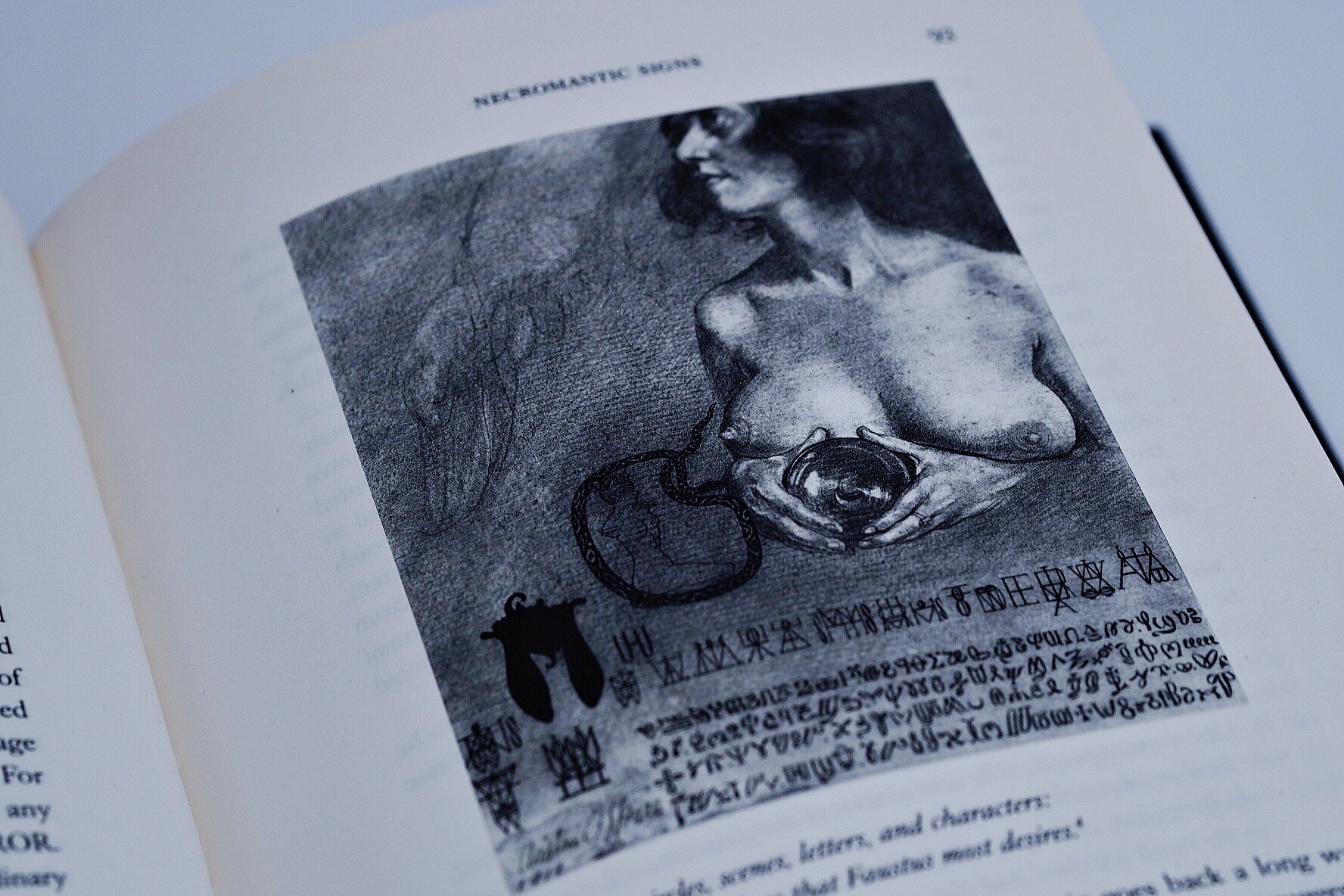

Which leads us to what is arguably Spare’s most important contribution to the history of occultism: his sigil magic. While sigils were a time-honoured stock item of Hermetic and Renaissance magic, they were invariably tied to astrological, numerological or kabbalistic foundations if not combinations thereof. Typically, they were also assigned to specific supernatural entities such as discrete spirits or demons. Seen within this context, Spare’s approach constituted a veritable revolution:

The big difference with Spare’s method was that he dispensed with pre-existing esoterica and external beliefs, so the sigils were no longer for controlling traditional demons, angels and what-have-you, but instead for controlling forces in the unconscious psyche of the individual operator.

Spare’s sigillization was a mode of simplification, paring an idea down into a condensed graphic formula.

[…]

So in short, in Spare’s own words, “Sigils are monograms of thought, for the government of energy.” (p. 74f.)

While his technical description is quite accurate, for Baker this is merely one episode out of many in Spare’s life and he refrains from making very much of it, devoting a scarce page to the subject, an illustration included, though recurring somewhat perfunctorily on it occasionally later in the book. He even omits to give any clear indication of what to actually do with the magical sigil once it has been constructed i.e. how to charge or activate it. While no reader can reasonably expect a complete how-to treatise on applied sigil magic here, this is one bit of contextualisation we would certainly have preferred to see. To an experienced magical practitioner, this may come over as a bit underwhelming, indeed as something of a put-off.

Instead, Baker pursues his narrative further by delving into the psychical research which was all the rage at the time, permeating all classes of society, with Spare and alternating friends conducting experiments involving materialisations, the evocation of spirits, and rain-making. Here, Baker confines himself to neutral reporting of these anecdotal events straight out of the arsenal of sorcerer’s lore without either endorsing or questioning their truthfulness, though he does point to varying versions of the same tales where available.

On 4th September 1911, Spare gets married to one Eily Shaw, a chorus girl and a single mother three years his senior, with whom, it appears, he was smitten almost on sight. The affair was shrewdly engineered by Eily’s mother who was very keen on marrying off her daughter to the young gent with the very promising future, the process being further expedited by Eily’s pretending to be pregnant. The young couple set up in a flat next to Sylvia Pankhurst, located in a well-to-do Jewish neighbourhood, which prompted Spare to delve into Jewish sacred literature. His hopes of securing portrait commissions from his affluent neighbours never materialised, and though his marriage ultimately proved a failure, as an artist he was still on a rising trajectory to success. His creativity knew no bounds – one major achievement being his best-known (and arguably most difficult) literary work, The Book of Pleasure (Self-Love): Psychology of Ecstasy, self-published in 1913.

For all his brilliance, his deep mystical insights, his originality of thinking and his singular artistic talent, Spare was anything but the world’s greatest writer or, for that matter, communicator. His prose can be idiosyncratic, woolly, contradictory, disturbingly vague, and downright cryptic, for all of which The Book of Pleasure is the perfect example. It is to Baker’s everlasting credit that he presents us with an exemplarily lucid and painstaking précis of its contents without endeavouring to forge it into some normative exegesis. It’s not that he ignores its shortcomings either: “his tortuous struggles to express his ideas in writing can be ponderous, awkward, and disjointed. The effect can be vexing to read […]” (p. 86) What is positive about it, deems Baker, is that it makes no pretensions “to bogus traditions or superhuman messages” (ibid.); instead, “The Book of Pleasure is simply a man speaking to his readers, without pretensions to leadership, aiming for an engineer-like practicality” (ibid.), though this reviewer would venture to suggest that the jury may still be out on the question of whether this not-too-lofty aim was actually achieved.

The plenitude of topics, ideas, concepts, references and influences making up Spare’s Book of Pleasure as a whole would merit an entire review of its own, but this is not the place for it. Baker covers them scrupulously, ranging from the Kia to Self-Love and the Death Posture, the unleashing of the mental energy of the unconscious, the tenets and basic mechanics of sigil magic (again, no charging techniques…) and the Sacred Alphabet (better known as the Alphabet of Desire), Atavistic Resurgence (actually Kenneth Grant’s term), and plenty more. What does bear pointing out in slightly more detail here is Spare’s peculiar position on reality in general.

As Baker observes:

When it came to reality, Spare saw the extent to which it was constructed from belief. We know the importance of belief from the sometimes dramatic results of placebos and “nocebos” (negative placebos, like the pointing of the witch-doctor’s stick that kills aborigines who believe in it) but there is a larger sense in which reality is the embodiment of lived belief.

Spare was less interested in promoting this reality or that reality, and more interested in the way people confined themselves to whichever one they had: he was less interested in what to believe than in how to believe. He saw belief as something free-floating, which could be channelled and re-directed to different objects ([…] like Freud’s descriptions of “libido”, which often sound like something out of hydraulic engineering). Spare, in other words, sought to conjure with belief itself. (p. 87)

This being one of the basic tenets of Chaos Magic as developed from the mid-1970s on, it goes to illustrate Spare’s seminal albeit posthumous impact on modern occulture. Aggregate his specific legacy of sigillisation techniques and his concept of “Atavistic Nostalgia” or Resurgence as well as his idiosyncratic “Alphabet of Desire”, and it would certainly be no exaggeration to posit that Austin Osman Spare was to contemporary occulture in general, and to magic in particular, what Eliphas Levi had been to Western esotericism in the 19thcentury.

For many years, however, he would remain very much a magicians’ magician: leaving his mark on insiders of the scene such as Gerald Brosseau Gardner or the Great Beast Aleister Crowley himself, but widely unknown to the occult public at large.

I recall attending a very well-visited New Age event in San Francisco in early 1979, featuring amongst other speakers Timothy Leary, who came on stage and, when asked about Austin Osman Spare, was quite obviously out of his depth – he had admittedly never heard of him before. Neither had the likes of Michael Harner, Alberto Villoldo and Harley Swiftdeer Reagan, when I interviewed them for the German occult magazine Unicorn in the ’80s. Around the same time, Spare was, aside from a very few specialists, also still unknown to the majority of members of the Fraternitas Saturni. In fact, it was probably I myself who introduced him to a wider German readership with my very first Unicorn article on his sigil magic back in May 1982. (Within the context of Comparative Literature, Mario Praz had actually mentioned him in a footnote in his classic 1933 study The Romantic Agony – quite ironic in view of the fact that Spare’s entire existence would shift very much into footnote mode once his halcyon days as a spectacularly celebrated artist were over.) All of which goes to show that, in contrast to his precocious career as an artist, his star as an acknowledged prime influencer in the occult world was significantly slower in rising.

Back to Baker, we find him amplifying Spare’s assumptions and doctrines by cross-referencing them with other authors and currents of thought within the history of ideas, both mainstream and occult. This is illuminating and educative even for the weathered savant of occultism.

Baker’s analysis of Spare’s relationship to psychoanalysis is exhaustive and astute. The latter’s less than generous comments on some of its big names such as Freud and Jung – “or ‘Fraud’ and ‘Junk’ as he called them” (p. 95) – is quite telling, however. There is a clearly discernible envy at work in Spare’s apocryphal-to-ridiculous claims of a lifelong friendship with Havelock Ellis, or of Freud, Krafft-Ebbing, Adler and Whitehead having consulted with him, with Freud even “using” i.e. stealing one of his theses etc. As he would brag before some of his friends, Sigmund Freud not only read his Book of Pleasure but even wrote to him “to congratulate him on his original thought” (p. 106), allegedly describing it as “one of the most significant revelations of subconscious mechanisms that had appeared in modern times.” (ibid.) However, as Baker wrily observes: “Sadly this letter has not been found.” (ibid.)

This, too, is typical self-absorbed, narcissistic Spare spinning a grudging yarn and dissolving the borderline between fantasy and objective factuality once more. By way of an aside, this pompous self-portrayal ties in seamlessly with his equally presumptuous claim of being the true inventor of Surrealism in art. A more reasonable assertion, albeit for Spare an obviously far too humble one, would have been to simply point out that he was one of its precursors. Baker addresses this topic at some length, pursuing several tributaries feeding this major current of art in Spare’s lifetime: psychoanalysis, trance induction, the apotheosis of the subconscious, the fascination with the grotesque, and, perhaps the most interesting, the spiritualist roots of automatic writing and drawing.

It is also to be noted that, in the course of his professional activities, Spare managed to ramp up quite a cohort of detractors and downright haters who were less than amused both by his art and his demeanour as chief editor of the art magazine Form. Amongst his critics were such celebrities as William Butler Yeats and George Bernard Shaw.

Come World War I (or the Great War, as it would be called till 1939), Spare was eventually conscripted to the Royal Army Medical Corps. And what a war he had! Posted to Egypt, where he was able to study hieroglyphics at first hand; on the Western Front he spent a night under a pile of corpses in no man’s land; “and when he was on a troopship bound for Africa and a torpedo struck, he remained calmly on the deck while everyone else jumped overboard at the cry of ‘Abandon Ship!’" (p. 122) – or so he would have his friends believe. Regarding which Baker observes tongue in cheek: “In fact Spare didn’t get as far as Egypt, although he did get to Blackpool.” (ibid.) Neither did he ever see combat, nor was he shell-shocked in the trenches of Flanders, as some later authors would have it.

Initially working as a medical orderly (and thoroughly hating army life and its rigid discipline), he was later posted to London and assigned, along with about a dozen other artists, to a studio where they were tasked with “illustrating a historical record of the conflict.” (p. 123) Some of the resulting oils are still being displayed today at the Imperial War Museum, and Baker devotes a few rather amusing pages to the goings-on behind the scenes at the time. Hint: not all that happened there was to Spare’s unmitigated delight…

In the interwar period, Spare experienced a severe downturn of his fortunes. His marriage was in a shambles, and while he and Eily never divorced, they both went their separate ways though remaining on friendly terms. Artistically speaking, the writing had been on the wall even before his military service: “Spare’s work may already have been dating and démodé” (p. 118), not the least because of his strong links with Art Nouveau which was generally beginning to fall out of favour. He was also hounded with recurrent charges of plagiarism throughout his life, most of them, as Baker argues convincingly, quite unfair and off the mark.

If success evaded him, it was not for his want of trying: while he managed to run a new art magazine, The Golden Hind, with an impressive line-up of contributors, it, too, finally failed as had Form before. And living in decidedly squalid circumstances most of the time, his triumphs were few and far between.

Isolated, rejected, almost defeated, the second half of Spare’s life was now beginning, down among the inhabitants of Borough: living, as he told Grace Rogers, “as a swine with swine.” (p. 141)

Nonetheless, Spare remained as creative as ever, producing writings and suites of pictures such as The Anathema of Zos: The Sermon to the Hypocrites, The Book of Ugly Ecstasy, A Book of Automatic Drawingsand The Valley of Fear, all of which Baker discusses in welcome elaboration, occasionally quoting some of Spare’s contemporaries and friends, e.g. Grace Rogers:

Amongst the pencil drawings […] there were many to equal old Master drawings but, unfortunately, they were drawn in penny exercise books or on postcards[…] (p. 143)

Nor does Baker himself refrain from assigning praise where praise is due. Consider his comments on The Book of Ugly Ecstasy for an example:

Finely-drawn and truly, disturbingly hideous, it is a riot of warty, dripping, hairy flesh, spewed frogs, scaled and rotting teeth, splitting faces and noses with a root-like life of their own. It goes far beyond Edmund Sullivan’s easy equation of the grotesque with evil, and instead seems to accept it almost lovingly on its own terms.

It contains some of the greatest grotesque art since the Middle Ages […] (p. 145)

Eking out a precarious living by assembling and installing home wireless (i.e. radio) sets, Spare manages on and off to sell some of his artwork to his more ardent and faithful collectors and admirers.

It was […] Duchamp who said that the great artist of the future would go underground, and in this respect Spare was ahead of his time, living in obscurity down in Borough. Living alone, he said, he had made great introspective discoveries, and he wrote “In our solitariness, great depths are sometimes sounded. Truth hideth in company.” (p. 149)

Living alone – and yet anything but, if his own words are to be trusted: “‘I have only to turn my head,’ he said, ‘to see the whole gang of familiars, elementals and alter-egos that make up my being.’” (p. 150) In view of his artwork and his general perception of the dream world representing a kind of “second life”, truer and of far greater import than that of everyday consciousness, we may probably take this statement at face value. Let’s not forget that Spare, as an established sorcerer with at least one veritable published grimoire (The Book of Pleasure) and an entire magical system to his credit, may most likely not be speaking metaphorically here.

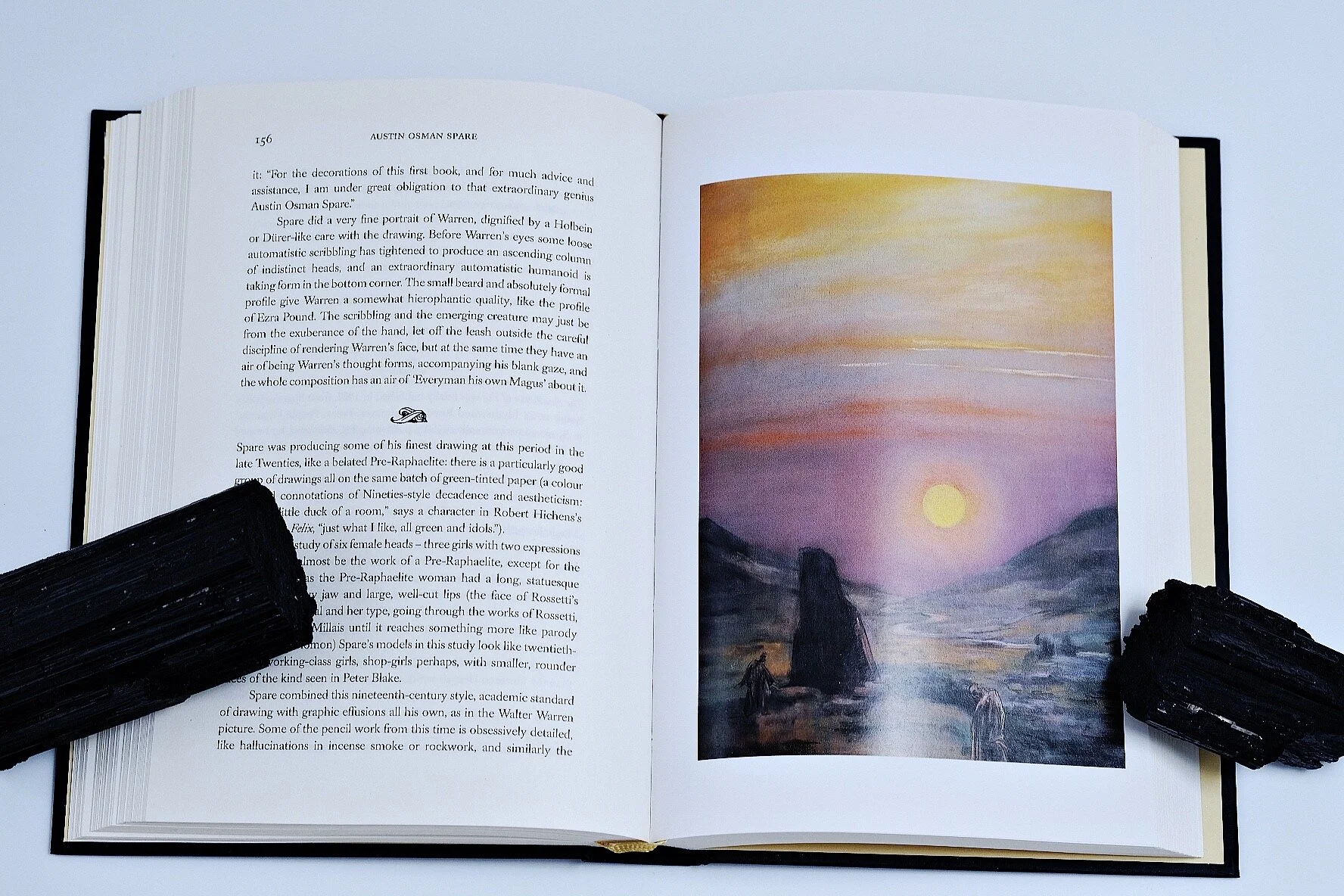

In the early to mid-Thirties we find Spare cutting out the middleman by organising his own selling exhibitions in his studio after several art gallery shows in the West End had flopped. His art became slightly more commercially targeted, focusing on portraits with a uniquely anamorphic touch and conducting what he termed “experiments in relativity”. In addition, he painted lots of “‘straight’ portraits and character studies of local South Londoners” (p. 185) with a strong focus on old women over seventy, whose longevity and psychological stamina he genuinely admired. Overall, however, he was beset by extended bouts of depression and heavy drinking in this phase of his life.

With the arrival of Salvador Dalí in London in 1936, Surrealism became all the furor and Spare’s friends and champions rushed to promote him as its most prolific British proponent, effectively rendering him with a new public identity. A lifelong aficionado of horse race betting, it led amongst other oddities to his creation of a set of “OBEAH CARDS for forecasting race results” which he sold in a hand drawn and a cheaper printed version, rechristening them later to “Surrealist Racing Forecast Cards”. Promoted via small adverts in the Exchange and Mart, it seems they were quite a success.

A year later, it appears that no one less than Adolf Hitler contacted Spare via the German Embassy, asking him for a portrait, which Spare adamantly refused to do. As with so many episodes in Spare’s life, the details are murky and only partially verifiable, but Baker does come to the conclusion that there may indeed have been something to the story, though it isn’t entirely clear what exactly. Spare himself did sport a small moustache at the time, and a picture survives, catalogued Self as Hitler, featuring his acrid rejection of the dictator’s commission request as an embedded text. Never at a loss for embellishing and magnifying his own yarns to the point of absurd exaggeration, Spare would in later years claim to actually have flown to Germany, somehow bringing Hitler’s portrait back “to incorporate it into an anti-Nazi artwork, perhaps even a magical one, or a work of surrealistic propaganda” (p. 181) – another tall story the tabloid press was happy to harp on.

Apparently he had finally learned how to spin himself as a character and effectively toot his own horn in public: from 1936 to 1938 his private studio shows were all quite successful and he managed to open the Austin Spare School of Draughtsmanship in his studio as well.

With the onset of World War II, Spare was employed as a fire warden after his volunteering for military service had been rejected, as had his offers of assisting in the war effort with his intricate theories on camouflage. After a bomb completely destroyed his studio during the Blitz (together with about two or three hundred of his paintings), he was essentially homeless and finally found shelter in a working men’s hostel, a turn of fortunes he chalked up to “Hitler’s revenge”. Even worse, he suffered a loss of memory and some degree of paralysis to his hands which left him unable to draw.

Distressed, badly traumatised, impoverished, physically and mentally impaired, the War period was undoubtedly the worst phase of his entire life. Laboriously exercising to regain the use of his muscles, he did, however, finally persevere and by the end of the War had resumed drawing and painting again.

In 1947, Spare, once more as powerful and original an artist as ever, staged his post-war comeback at the Archer Gallery, “a slightly eccentric space” (p. 201) run by the Australian surgeon-turned-art-therapist and anthroposophist Ethel Morris. The exhibition was a new, long yearned-for triumph, with buyers queuing up outside waiting for the doors to be unlocked. It was also well received by the press and its art critics. Baker gives us the rundown of the works presented, foremost amongst which were Spare’s “siderealist” portraits of Hollywood film stars, not at all a standard motif at the time, which would later, posthumously, earn him the reputation of being the first British Pop artist.

The real life changer for him, however, came in 1949 when he met Steffi and Kenneth Grant. Steffi was a model and an aspiring artist herself, whereas eminently well-read Kenneth, a former student and factotum of Aleister Crowley’s (who had died two years before), was deeply involved in occultism in general and magic in particular. The three hit it off immediately. It was to prove a long and productive friendship lasting right up to the very end of his life. Amongst the works spawned by this co-operation were Spare’s manuscripts “Logomachy of Zos” and the “Zoetic Grimoire of Zos”, as well as the unmistakably Grantian titles of many of his later drawings.

What's more, this relationship laid the foundation to Spare’s fame in posterity, if not so much in the mainstream world of art, where he is widely being ignored to this day, as in the realm of occultism and magic: his innovations and concepts are being propagated, discussed, interpreted, co-opted and expanded upon on a much wider scale than they ever were during his lifetime. Whether it is sigil magic; his focus on controlled obsessions inoculated into the unconscious by trance work; neo-shamanistic atavistic resurgence; sex magic (including “copulation with the ether”, as he would word it); his antinomian rejection of traditional, formalised ceremonial magic and its countless dogmas; his radical metaphysical individualism; his “Neither-Neither” principle and his maxim of adopting “non-attachment non-disinterest” – these and many more are quite alive and kicking, integral components of 21st century magical discourse. Austin Osman Spare: shape shifting from a highly eccentric and socially awkward, art-obsessed outsider to the “church father” of Pragmatic, Psychological and Chaos Magic – one unique transformation that is quite a magical story in its own right.

Another, more mundane innovation that came about in 1949 was Spare’s starting to organise art exhibitions in local South London pubs, promoting this hitherto uncommon format as being more “democratic”. Unlikely as it may initially have seemed, they proved to be very rewarding, with significant numbers of pictures being sold. Unheard of at the time as well: amongst the offered items where several notebooks of Spare’s featuring up to forty-eight sketches each, the copyright to which would be transferred to the buyers to do with as they pleased, including publishing or passing them on as their own work. Whilst Spare was well known to have refused lucrative portraits and other commercial commissioned work throughout his life, he had by now obviously learned some of the basic rules of marketing governing the arts sector of his era.

As for Kenneth Grant’s influence and impact on Austin Osman Spare, Mr Baker gives us the following summary overview:

Grant had come up with a magical name for Spare, “Zos vel Thanatos”. Spare took to it happily, but it was very much Grant’s coinage rather than his: in fact Spare had to ask what it meant, a little cagily: “By the way, translate ‘Zos vel Thanatos’. I believe my guess is right but both are elastic words.”

It means “Zos or Death”, typical of Grant’s dark sensibility. Grant had also founded a Spare religion, the Zos Kia Cultus, described by Grant as embodying Spare’s idea that any belief, sufficiently believed by the whole being, becomes “vital or organic… it is possible to reify wishes, dreams, desires, etc… The mechanism of this sorcery may be described as an ‘as if’ potential, latent and fictive, transforming into an ‘as now’ ecstasis, potent and actual…”. Grant’s especial influence on Spare was to whip up his interest in witchcraft, orgiastic sabbaths, and lascivious old women. (p. 238)

Thus, it is entirely reasonable to assert that the “late Spare” is as much a product of Kenneth Grant as his own, the latter operating as his acolyte, image coach, muse, interpreter, exegete, formal education mentor, proof-reader, part-time ghost-writer and, posthumously, his promotion agent. However, it should also be pointed out that none of this was coercive, Spare being more than happy to comply, at least most of the time, for reasons of his own; not the least being that, from a certain point on, he seems to have been exceedingly infatuated if not madly in love with Steffi.

If Baker is to believed, and there is nothing to indicate the contrary, even the famous Mrs Paterson’s very name wasn’t exempt from Grant’s all-encompassing impact: “it seems to be only in the Grant era of Spare’s life that she takes on the name of Paterson.” (p. 239) Moreover, it was only then that Spare fleshed her out considerably, with Grant cheerfully chiming in to forge a mutual fantasy of a full-blown witchcraft cult with all the trimmings that would have beefed up even a Spanish inquisitor’s wettest dreams.

After an excursion into the mainstays of Kenneth Grant’s fictional non-fiction and a series of fairly ludicrous anecdotes centred on the shenanigans of the early 1950s London occult underground, including Austin Spare unwittingly participating in a magical feud between Gerald Gardner’s coven and Grant’s Nu-Isis Lodge, Baker moves on to an informed and perceptive assessment of Spare’s actual status in the history of modern art.

As much as he can seem of his time or even ahead of it, Spare was equally behind it. He was an interstitial figure, “in-between”, essentially out of step. He wasn’t the last Old Master or the last decadent, nor was he quite the great precursor of Pop, abstract expressionism, surrealist automatism, Lettrism, or appropriative, role-playing art (with his pictures “of” himself as Christ, a woman or Hitler, anticipating Cindy Sherman). And yet – like the principle of “fourfold negation” that he seems to draw on in The Book of Pleasure – it's not that he absolutely wasn't a precursor of those things, either.

As for being ahead of his time, it is also noticeable that he often looked belated to contemporaries. […]His career seems to have been over almost before it began, until he starts to sound like the greatest artist Britain never had. (p. 253)

Spare, the unfathomable paradox: what may seem like a limp, lazy-minded cliché at first glance, is to this day probably still the best explanation we have for the unmitigated fascination irradiating from Spare the artist, the sorcerer, the visionary, the dreamer, the human being.

Somewhat out of the blue, Baker comes up with a final facet of classification: “At the very least, perhaps, we should include Spare in what Peter Ackroyd has identified as the ‘Cockney visionary tradition.’” (p. 255) As he refrains from expanding on this statement, it is up to the reader to further pursue this pointer if so inclined.

On 15th May 1956, Austin Osman Spare, the “strange and gentle genius”, as the Evening News would describe him in its obituary (p. 257), died in South Western Hospital, Stockwell of peritonitis following a burst appendix. Physically, he had been poorly for a long time, suffering from a slew of ailments including gall stones.

Baker’s farewell is as touching as it is appropriate:

It was generally agreed he had simply turned his back on fame and fortune, which was not quite true, although things certainly turned out very differently from the glowing future anyone might have predicted from the perspective of 1904.

What had done for Spare? Perhaps it was the class system, or lack of education, or a touch of mental illness; or perhaps – as I’d like to think – it was nothing at all: “Only the gods can distinguish failure from success.” (p. 257)

In his chapter “Coda: The Afterlife”, Phil Baker offers a very brief overview of posterity’s dealings with Spare and his work including an unanticipatedly literal musical coda. His “Note to the Second Edition” features some updates and corrections, followed by a list of colour plates (twelve in all, including the cover image) and illustrations in the text. Endnotes, a bibliography, an extensive index and acknowledgements round up the book.

Truly a one-of-a-kind biography, worthy of its one-of-a-kind subject.