‘ANARCH’ by Gast Bouschet. Reviewed by Frater Acher.

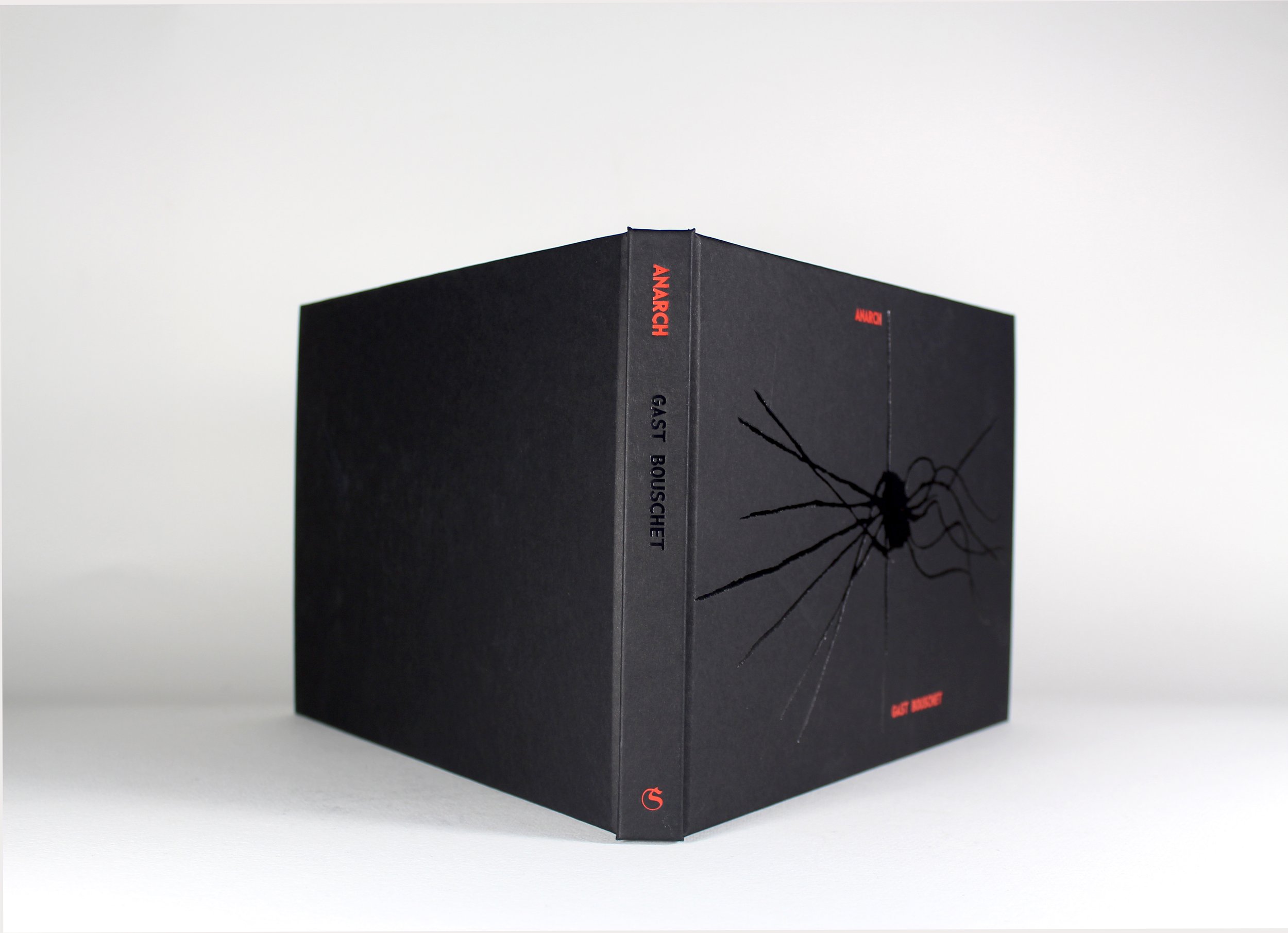

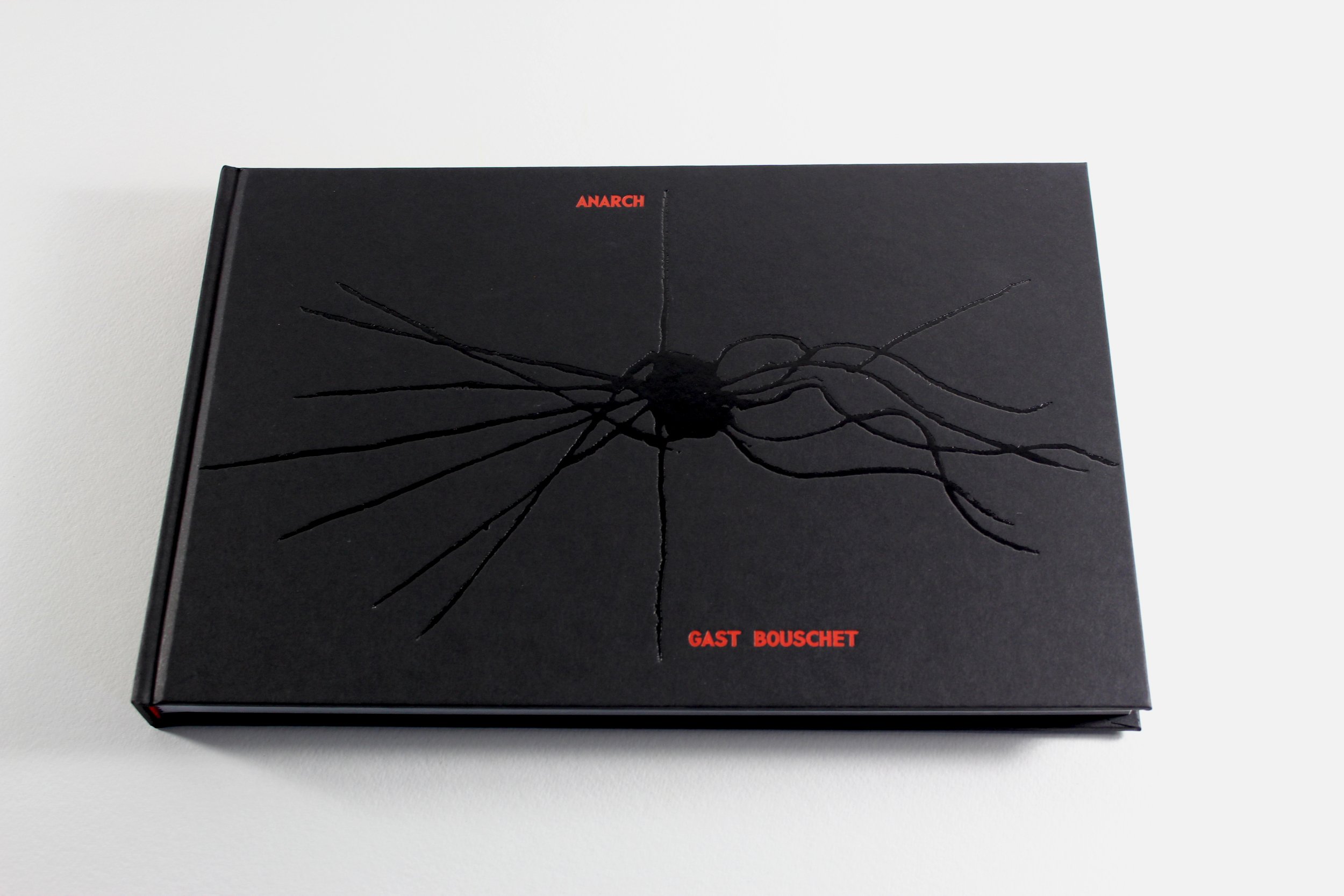

Review: Gast Bouschet, ANARCH, London: Scarlet Imprint, 2023, limited to 800 hardcover copies

by Frater Acher

A dream: I am wearing a mask frozen to my face. No one around me seems to notice. I am surprised by the stiffness of the chin piece and wonder if it will adapt to my natural movements or if it will remain as rigid as it is now. To avoid attracting attention, I act as if it were a human face, but it is not. (p. 36)

Gast Bouschet has given us a book about the place where death and life are interwoven in a Round Dance of day and night, interpenetrating and scratching at each other, deeply entangled. For Gast Bouschet, this place is a forest in the Ardennes. Or, rather, Gast has fallen from the physical locus of a forest in the Ardennes into this place of art and sorcery.

Now a forest can be entered from all kinds of directions. Unlike a house, it needs no gate or door to mark its thresholds of wood and thicket. The walls of a forest are also its passages; and so it lies at once open and closed to the approaching wanderer in all directions.

It is the same with Gast's book, which is about, inspired by and born of a sorcerous forest and seems to have taken on many of its characteristics.

ANARCH can be read as a revolutionary manifest against the modern art world; a synthetic and yet brutal realm, suffocated by exploitative curation and capitalist investment strategies. Equally, ANARCH can be approached as an initiatory passage into the chthonic body of the underworld; a body that encounters eroticism, pain and delight just as much in decay and death as in germination and birth. Or ANARCH can be devoured as a satanic celebration of the black sun, the alchemical principle which does not offer light and warmth, but dissolution and decay, in order to break open objects – and this includes human bodyminds – for their flesh to be permeated by a lived understanding of the Other.

In all three of these ways, this book is a deeply personal testimony of an artist who became a sorcerer, and a sorcerer who turned into an undead. And it is in this notion of being undead that at least this reviewer found the charm, the sting, the depth and the delicious confusion of this book. Because it is precisely in the uncanniness of ANARCH that we also encounter its hope of a rediscovery to participate in this (under)world in a more authentically human way.

When Bram Stoker coined the word “undead”, he was inviting us to rethink the polarity of life and death, to break it open, and to make room for transitions and in–between states that are no less significant in their ontological presence than the one–dimensional declarations of being either dead or alive.

As such, an undead is one who is as familiar with life as with death. Their culture is at once sepulchral and passionate, marked by pain and yet life-affirming, profoundly transient and yet insisting on participation. Gast’s works now transport this original thought of the undead into the black horizon that straddles the concepts of art and sorcery. A habitat, as the book goes to show in words and images, animated more by disturbing and unruly than by aesthetically flattering artefacts.

ANARCH reminds me of the image of a palimpsest made of one’s own skin and written in one’s own blood, illustrating various layers, crusts and scarring of one’s own life and death. No human being is just one thing, one identity or one body at a time. We tear apart and we stack up. We are always legion. And in our best, most painful, most intense moments, we are no longer a body sealed off by membranes of skin and thought, but we begin to spill, to bleed, to eviscerate, to mingle wounded and wide open with our environment... In this sense, when it comes to entering the forest that is ANARCH, it is not “the crack that lets the light in”, but the wound that lets us out and into the wilderness around us.

To read this book with the right attitude – or to gain the right attitude by reading it – Gast invites us to imagine an alchemy no longer bound to the one goal of creating gold. Not to force nature beyond itself, as Julius Evola once put it, is the concern of this black alchemy, but to decompose bodies, to open bodies so that new encounters from within and without can take place. One has to imagine such an alchemy as an anarchic process, as a radical intervention, without a beginning and without a goal and without lab assistants or human supervisors. Rather, imagine it as a landslide or a festering wound. As something that – whether in frenzied, blind violence or in slow inflammatory decomposition – goes its very own way, insists on it, irrevocably, and carries the human being with it, as it were, as hostage in the far periphery of its undertaking. Here humans are no longer co-creators, certainly not semi-divine gardeners or living pinnacles of creation themselves. Rather, we are a skin pocket filled with delicious provisions for which a horde of micro- and macro-predators is already eagerly waiting.

Such black alchemy, or alchemical sorcery as Gast calls it, has a good chance of ending with the death of the people involved in it. So, like reading this book, it is not a light undertaking, not a preparatory school, and certainly not a human-centred anthropomorphic art. Instead, it is existentialist art of a kind one could hardly imagine more drastic, more radical.

Gast’s images that bear witness to this speak volumes, and yet they are no more than glimpses through a keyhole into the wilderness beyond.

Several times Gast emphasises that he is not giving a detailed transcription or instruction of his own magical practice. At the same time, he implies that such a practice would touch on several taboos of Western cultures as well as be resonant in many ways with African Vodun cults and their understanding of corporeality. The reader who is well versed in the subject can imagine everything else, and enjoy the fact that Gast thus spares his book the fate of being read as a modern, possibly even black magic “grimoire”.

Nothing is further from this book than to present a grammar of either environmentalist white or satanically blacknature. Rather, it thrusts the reader backwards into a pit, dug in a remote, abandoned patch of forest, where we come to lie among earth, roots, leaves and decaying animal bones – oh yes, and also next to our author himself. In this kind of sacrificial intimate communion, Gast then takes us into his chthonic underworld.

To get a glimpse of it, I recommend imagining meditating with a festering wound and feeling deep peace. I recommend imagining lying in a forest clearing at night with an open cut, feeling more “with yourself” than ever before. Or imagine lying on a mattress in a forest hut with chronic pain, and feeling a joy that is not born from the absence of pain but from an entirely different encounter.

Now we, as readers, will not have much joy with ANARCH if we are not prepared to engage with such paradoxical situations and sensations. The core of this book is to “shift” our point of view so that we can see that these apparent paradoxes are but simple illusions. Illusions born of the at least three-thousand-year-old fantasy that the world has to subordinate itself to man.

For many Western recipients, it was Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) who began to radically expand the concept of art in the 1960s. Not only did he design his own biography as a work of art, i.e. he pierced the membrane between himself as a human being and the art surrounding and created by man. But, he broke a hole in the thick walls of museums and brought art into the social space. Above all, however, it was thanks to Beuys that the concept of shamanism was introduced into the concept of art and that the natural and animal raw materials he used were once again understood as materia magica.

In this sense we definitely find animistic echoes of the spirit of Beuys in Gast’s works; however, in an uncompromisingness that is completely appropriate in the face of the collapse of the human habitat in which we have found ourselves since the 21st century at the latest.

Gast’s ANARCH, one might say, brings the spirit of Beuys down into chthonic depths; brings it to lie beside us, as it were, in the sacrificial pit mentioned above. From there, Gast’s book buries us alive, takes us on a satanic–alchemical journey to leave us injured, wounded, and fully given over to transience as undead revenants in the 21st century in new and diabolical forms. And it is in this undead form that we see a new understanding of humanity flash forth. That is, if we are willing to surrender to the spirit of this book in its radicality.

Beuys’ wax, felt and animal skins, which unsettled the white space of the museum and pierced it with their presence, have, with Gast turned into roots, blood, earth, ashes and a hive of living forest presences as his sorcerous artist collective. Only the museum itself has been left far behind in Gast’s current works. It is, after all, the notion of curation to which they declare partisan war; may such curation take place in museums, temples, or books. Gast’s work cannot be separated from the vivid black background from which it emerges. No longer is the art cut out from its living ecosphere and curated for display, but the viewer themselves is thrown into the role of the intruder. With our touching of the book and glancing at its wild and dark images, it is we who break into Gast’s art, stir it up and disturb its natural process of transformation.

Gast’s photos of his decaying artworks out in the forest are at once vulnerable and wounding, soft and poisonous, like the touch of a fungal spore whose landing on our skin is imperceptible, yet crossing the fragile threshold of our skin unhindered. Gast’s photographs are undead in the original sense of the word: like scar tissue or cornea, they still belong to a living body and yet already carry the seeds of death within them. They point us towards a black horizon that stretches out underneath their paper-and-ink skins, at once wide open and completely closed in on itself.

Throughout ANARCH, the impenetrability of the subject for the unaffected outsider is beautifully balanced with the intimacy in which Gast presents his work. On the roughly 120 pages of written texts, however, it is Gast’s own voice that lends a timbre of familiarity and mutual proximity to the book that is a magnificent accomplishment in itself.

The texts develop from Gast’s arrival in the forest in the Ardennes to more advanced works in the following years. The fact that the author and publisher have preserved the authentic sequence of the texts’ creation and made it visible through inserted dates allows the reader to walk in perceived unison, slowly, with many pauses, together with Gast through the enchanted forest of his life and work.

Even in its most sharp and poignant moments, the text in this way always remains vulnerable and ephemeral, like Gast’s artworks themselves, which by now have been many times drenched by the seasons, soaked, frozen through, and are finally wearing their bones on their skin, or simply have been scattered by wild animals.

ANARCH is not about theoretical paradigm shifts, practical instructions on sorcery, or putting any specific thought or object of substance into the reader's hands. Instead, this book wants to enchant us and it succeeds masterfully. Clearly, this is not the enchantment of romance but that of the ancient, archaic necromancy which turns the undead restless and might awaken some of them.

May this book walk through many hands, taking from them something of life and giving something of death. May we, with Gast Bouschet’s help, rediscover our own wounds as the places where we meet an unknown world, and from where art and sorcery break their untrodden way.

Quotes from ANARCH

The black light that shines at the core of nature has lost none of its power and is still able to put us in touch with our roots and the reality of the all-consuming fire of time. Yet few today seem to have a yearning for an art that aims at chthonic realms, which in their unfathomable depths always merge into cosmic dimensions. (p. 1)

The dark arts are an expression of a philosophy of alterity, a politics of heresy and a metaphysics of revolt that aims to change our being in the world. […] The dark arts involve tactics of resistance and revolt, but their greatest strength lies in their ability to conceal. (p. 2)

The dark arts are not something from the past, they embody timeless techniques for renewing the world through visionary experience. What we need is a new form of perception that enables us to see the world through the eyes of the Other. (p. 3)

At our core, we all have a radical alien essence. Sooner or later, it will shift us from flesh to a multiplicity at one with existence. (p. 7)

Sorcery is not concerned with artistic and social validation, it’s essentially a way of work-ing and existing outside cultural and social bonds. (p. 8)

The way I see it is that we have two options: either we passively endure fatality or we actively work and think toward death. (p. 11)

To work with the universe, we have to draw it into the body and make it become part of us. […] It is a wisdom as old as humanity itself, but what empowering practices like sorcery can do in these times of depression and anxiety is to create a reciprocal relationship with the planet and give us a new sense of agency. (p. 15)

I cut off my human head and devote myself to the empty darkness that it leaves behind. […] It is only from a position of radical equality that we can launch the sacred conspiracy that will free the body from its head and the earth from its masters. (p. 18)

Sorcery deals with the forces that bring disease and death into the world.

However, this should not lead us to believe that sorcery is evil. (p. 36)The alchemical vessel does not enclose the injured organs,

but consists of them. (p. 44)We cannot help but proceed with patient humility

and glide slowly into the dragon’s pool. (p. 23)Saturn is the damned beast whose horns of pain

push us down into the groundless ground. (p. 24)